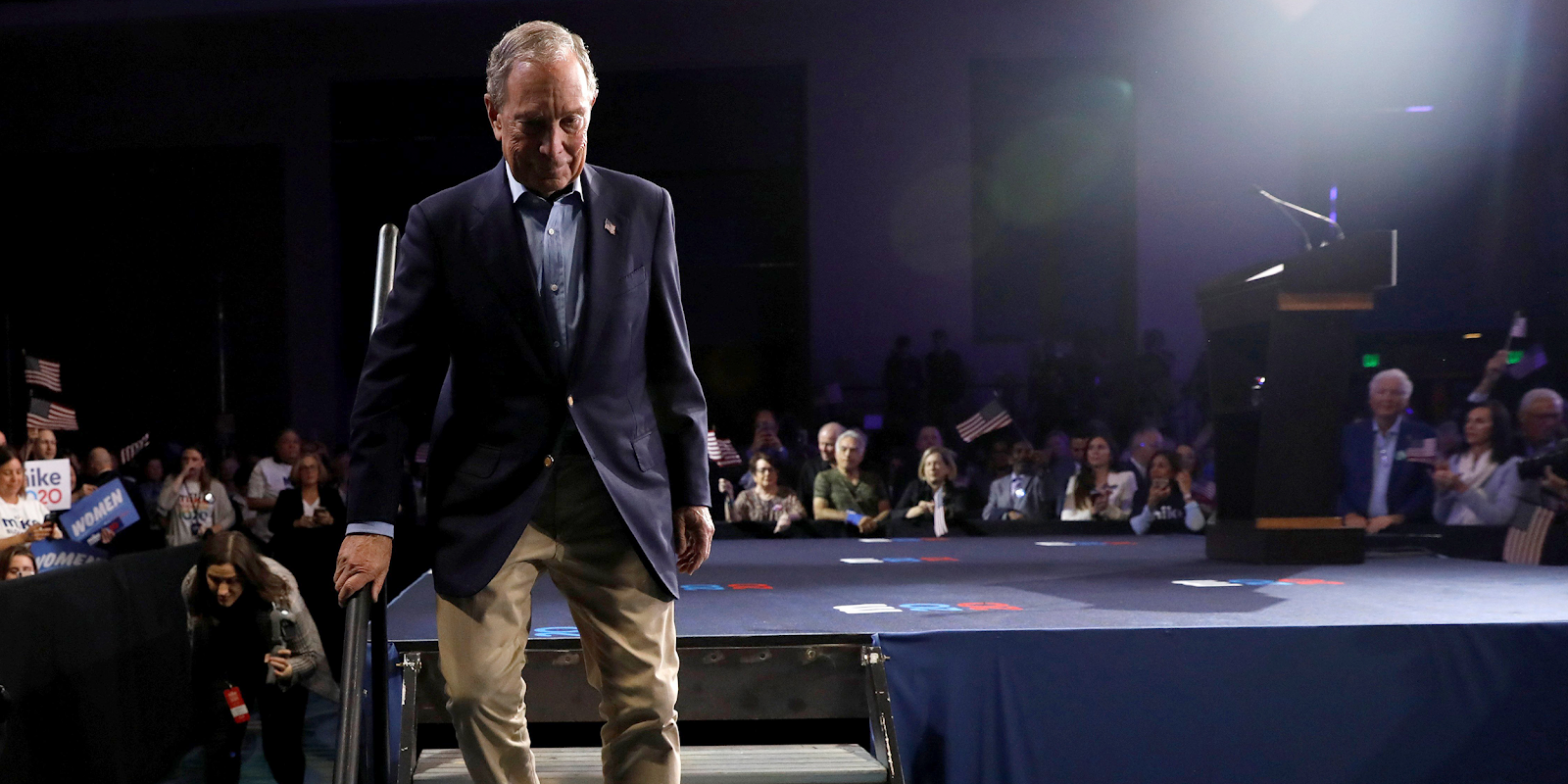

Now you see him, now you don’t; news media mogul and former mayor of New York City Michael Bloomberg began his short-lived campaign for the 2020 Democratic nomination when he filed a statement of organization with the Federal Electoral Commission on November 21, 2019, founding Mike Bloomberg 2020, Inc. Within three days, the first field offices were being opened in Northern Virginia, just outside of the District of Columbia. Within a week, money was being funneled from Bloomberg’s own pockets into establishing field offices in nearly all 50 states. Within a month, the campaign had hired over 2000 staffers. By the time it was all said and done, Bloomberg had spent over five-hundred million dollars of his own money on his campaign—according to a report published by Business Insider, constituting one of the greatest single campaign expenditures in American history.

This was over a span of four months—in only sixteen weeks, Rome was built, and on Super Tuesday, Rome had fallen. Bloomberg concentrated more than 100 offices in Super Tuesday states, where his infrastructure quickly exceeded that of his opponents. For instance, in Senator Elizabeth Warren’s (D-MA) home state of Massachusetts, he established six field offices, four more than Warren and five more than former Vice President Joe Biden, who ultimately won there with 33.6% of the vote. Bloomberg received 11.8%, falling short behind Biden, Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT), and Warren.

The Democratic hopeful only received 58 delegates for the Democratic nomination on Super Tuesday. In American Samoa, out of the total of 351 ballots dropped into a wooden box in Pago Pago on March 3, Bloomberg was selected as the nominee on 175 of them. He received 49.9% of the vote, a plurality victory, and his only successful contest. He conceded a day later on March 4.

When a regional-level Bloomberg organizer, who asked to remain anonymous after they as well as most of the Bloomberg staff had signed non-disclosure agreements, first heard the news that Bloomberg had dropped out, it was after they had driven to their local Bloomberg field office to check in for work. Much to their surprise, they found the doors locked, and most of the indoor furniture gone.

“It wasn’t like there was much there anyway,” they said in a conversation with The Politic. “We had received money from the campaign to buy furniture—but we had to build everything up so fast that we couldn’t wait for deliveries to come in—we just used folding tables and chairs.”

The majority of Bloomberg’s battalion of state offices were established with deep pockets and high expectations, but few guidelines and instructions on how to actually allocate their funds.

“It was ridiculous sometimes—everything was happening so fast and we had poor communication with the central office on what we were supposed to be doing,” one anonymous former organizer from Bloomberg’s Washington office said in conversation with The Politic. “They wanted us to have a debate watch party, for instance, but we couldn’t get money approved for a TV. Instead, they gave us this very expensive 100-foot projector. We went to set it up using the laptops that the campaign provided, only to discover that the office hadn’t been equipped with Wi-Fi. It was the night of the debate.”

Disorganization soon became a hallmark of working in the field offices in Bloomberg’s campaign, the primary grievance of his staffers. “Our office had three printers because one extra was ordered by mistake, but we never managed to get a microwave,” said the organizer from Washington. Accounts of miscommunication, fumbled responses and egregious errors proliferated testimony from Bloomberg staffers in a number of reports published in the aftermath of his campaign’s collapse—some organizers came to their offices to find them locked, others came to work to find that half the staff had come to work, punched in, and went home early seeing that their candidate had lost.

There were apparently always issues with accountability in the campaign’s day-to-day operations, according to several former staffers in correspondence with The Politic. Some organizers would be assigned duties to knock on 100 doors and make 200 phone calls in a day, and were only able to complete half of it by the time their shifts were over. Other former staffers, when trying to contact their state office or supervising regional offices to report issues, wouldn’t hear back for days on end.

In an effort to lift his monstrously-huge campaign off the ground so quickly, Bloomberg had promised two things to his staffers: a big check, and job security until November, even if he didn’t become the nominee. Seeing this enticing offer, many Democratic organizers, particularly young field organizers fresh off the campaign trail in Iowa, scattered to field offices all across the country to take Bloomberg up on his offer.

“Many people quit working on other down-ballot campaigns to come to Bloomberg,” said a local field organizer from Texas. “I left my local candidate to come work for Bloomberg because he offered to pay extremely well, but I also know young people who came from Iowa for jobs, or even campaign managers for small races who left their candidates on short notice to come work for Bloomberg because of the job security he promised.”

On top of that, it was a presidential campaign—many of the staffers interviewed were urging to be part of something bigger.

“When I had a chance to work on a presidential campaign, I withdrew from my spring semester of college,” said the Washington organizer. “I thought I was going to be in it for the long-haul, but now I’m unemployed.”

The campaign had claimed its staff in six key battleground states—Michigan, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Arizona, Florida, and North Carolina—would be paid through the first week in April and have full benefits until April. They could also have their CVs dropped into the Democratic Party’s hiring pool in what one staffer described as a “competitive hiring process.” Regardless, these jobs are not expected to pay what Bloomberg promised, that is, if they even existed at all.

“I was told that we would be entered into this competitive hiring process,” said the Washington organizer. “When we asked if this would be with the Democratic Party, working with the Democratic Convention in the summer, or getting a spot working in a local campaign—they just said that it would be somewhere—what does that even mean?”

This promise that it would all come out in the wash was as incongruent as the campaign. As the Texas field organizer stated, “when our office tried to reach out to the state office, they just gave us a bunch of ambiguous answers about what was going to happen next—we knew as much as they did it seemed.”

The main 100 days of the campaign was a “wild ride” according to the Wall Street Journal’s report. And that ride ended with a swift stop; staffers began to get the axe in the central campaign office first. These staffers, who were supposed to maintain communication with state and regional offices, suddenly didn’t exist. The head of the snake was cut off, but the body continued to writhe as 2000 employees across the country were suddenly left without answers.

“I think the communication was really contentious coming out of the central office,” said one organizer who was in correspondence with the New York office in the days leading up to Super Tuesday. “We just always felt a step behind everyone else when it came to what was happening.”

For most of these staffers, things are looking bleak—especially amid the recent outbreak of coronavirus and the flat-lining American economy. Many campaigns for both regional and national candidates are suspending their hiring processes—either not taking on new staff entirely, or continuing to interview potential staff and keeping them on reserve for when circumstances hopefully improve.

“For right now, it’s a lot of sitting and waiting,” said the Washington organizer. “Hopefully something will turn out.”