It’s October 2017, and Eric Schmidt is standing in front of a crowd of reporters in downtown Toronto. He is still the chairman of Alphabet, the oft-forgotten behemoth parent of Google. A few months from now, he will step down and take a role as chairman of the U.S. Department of Defense’s Defense Innovation Advisory Board. Already, though, Schmidt is curious about what it would be like to use his enormous private influence in the governmental sphere.

Schmidt is comfortable with the press. “[Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau] invited me to come chat,” he shares, speaking casually of a meeting two years prior. Trudeau, Schmidt recounts, said: “We want Canada to be Silicon Valley plus everything else Canada is.”

For Schmidt, Trudeau’s pitch seemed different from the ambitious statements politicians often make. “Somehow I believed him, I think because of his socks,” he jokes, referring to the Prime Minister’s fondness for sporting vibrant socks at formal events.

The high-profile event—with a guest list including Trudeau himself, former Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne, Toronto Mayor John Tory, and distinguished Toronto real estate developers—marks the official appointment of Sidewalk Labs, an Alphabet subsidiary, as the Innovation and Funding Partner to develop a small but extremely valuable plot of land on Toronto’s eastern waterfront.

Although at the time it is unclear exactly what the project would look like, a flurry of activity in the following months—led by a team of experts in private equity, technology, and urban design—will culminate in a proposal for a high-tech neighborhood unlike anything North America has ever seen.

Just over two years later, the blueprints will be ready, public support will be mostly mobilized, and Sidewalk’s team will be sitting on their hands, waiting for final government approval before they can break ground.

***

Trudeau’s vision of turning Canada into an innovation hub was at first the job of a tri-government agency called Waterfront Toronto. Since its inception in 2001, and with the help of collective efforts from the municipal, provincial, and federal governments, Waterfront Toronto has worked to revitalize over 2,000 acres of brownfield site on the shores of Lake Ontario.

Wanting to tackle a more ambitious project, the agency issued a request for proposals (RFP) in April 2017. They were searching for a partner, one with “invention ingrained in its culture” that would “lead the world” in building cities with revamped business and climate-positive practices.

Mazyar Mortazavi, a member of Waterfront Toronto’s Board of Directors, shared his logic with The Politic: “The public and private sector[s] need to be collaborating and working together because the traditional model of publicly funded solutions are…just not the way that they used to be.”

The focus of Waterfront Toronto’s RFP, a 12-acre area called Quayside, is different from what you’d expect to find just outside of a large city. Established in the early 1920s as an industrial hub, Quayside—sparsely populated and devoid of shops and high-rise buildings—is instead characterized by its sprawling parking lots and aging industrial-era warehouses. Sidewalk describes it in their plan as the “largest underdeveloped parcel of urban land in North America.”

Sidewalk Labs jumped at the opportunity, launching a $1.4 billion planned development project in Quayside, the first of its kind. They proposed transforming everything—from crosswalks to building materials to weather-adaptive canopies for buildings. Despite oversight by a tri-government agency and the solicitation of feedback from tens of thousands of Torontonians, however, many remain wary of welcoming a foreign big tech firm with open arms and asking them to build a community.

***

Sidewalk’s vision captivated Waterfront Toronto. “The[ir] proposal tr[ied] to push the envelope on how urban development could be done,” Mortazavi recalled of Sidewalk’s plans.

The scope of their proposed innovations is vast. One technology that Sidewalk Labs is eager to showcase—“Dynamic Street,” a collaboration with MIT’s Senseable City Lab—proposes that a series of adjoined concrete, hexagonal tiles will eventually render curbs and street lines obsolete. Each tile—equipped with sensors, heating coils to melt snow, and an LED light—could transform an urban space from a road to a bike path, sidewalk, or plaza in a matter of minutes.

While working in New York, Joe Berridge, now a partner at Toronto-based city planning firm Urban Strategies, moved in the same professional circles as Dan Doctoroff, then Deputy Mayor for Economic Development and Rebuilding for former Mayor Michael Bloomberg.

“Quite frankly, [Doctoroff, now Sidewalk’s CEO] was the most impressive city-builder I’ve ever had anything to do with,” Berridge shared with The Politic. From his experience working alongside the current Sidewalk boss, Berridge came to know Doctoroff as “just an incredible character, like a polymath driver guy, and when I heard he was coming to town with Sidewalk, on a personal level, I was ecstatic.”

Berridge, whose firm consulted with Sidewalk Labs in developing their Master Innovation and Development Plan (MIDP), sees an opportunity for Toronto to position itself as a leader in innovative city building practices, right down to the wood frame construction. “The limits of wood are being pushed impressively,” Berridge explained. “The production process is much lighter and much more energy-efficient.”

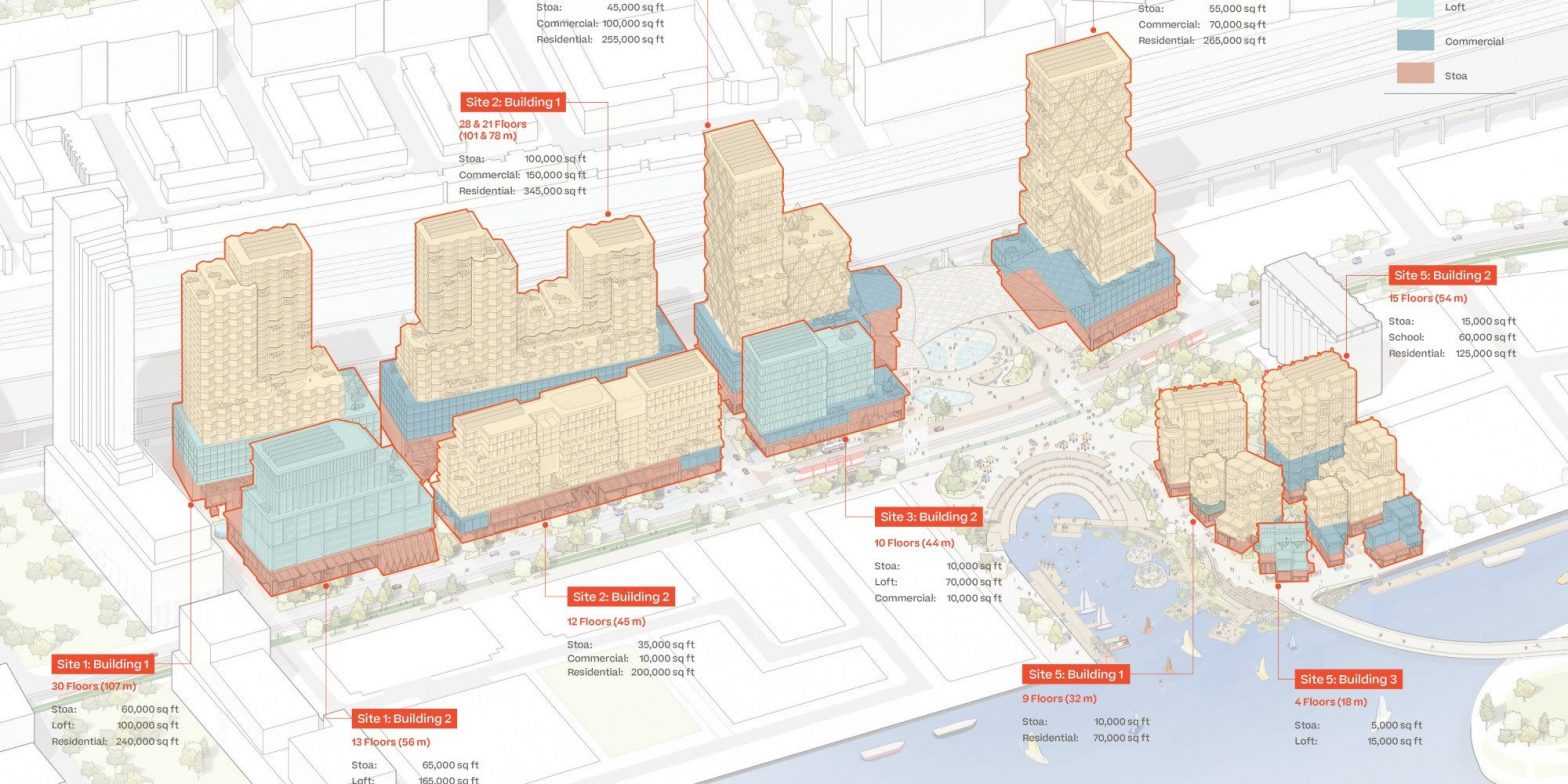

Berridge believes that the 1,524 page MIDP—which boldly proposes a 190-acre development project, expanding far beyond the 12-acre Quayside area for which they originally applied—encompasses both conventional and unconventional approaches to city building. “There’s a wonderful blend of the conventional street-grid city and the public-space city being the base on top of which something more imaginative and innovative is being built,” he said.

Its 18 services and systems along with subsequent 52 subsystems—many of which have been tried elsewhere—nonetheless face wide-ranging criticism. The Dynamic Street, for instance, will have its fair share of roadblocks. “Customization…will probably create inefficiencies…which involves extra costs and training,” Berridge explained. Further, “there could be liability issues too…when someone blames the new street design for creating an accident, as any lawyer will do.”

***

Not everyone shares Berridge’s confidence in Sidewalk.

“It’s not a good idea to give a corporation, and particularly a corporation with monopoly power, such latitude in planning and developing and running municipal infrastructure,” said JJ Fueser GSAS ’98 & ’02 in an interview with The Politic. As a member of #BlockSidewalk, a sizable movement against the Quayside plan, she is concerned about potential data and privacy issues. For example, residents could access services like subsidized housing only after registering for what Sidewalk calls Distributed Digital Identity Credentials. An innovation only vaguely touched on in the Sidewalk plans, the DDICs would allow “the company [to] monitor, in real time, whether your income exceeded thresholds for social supports,” Fueser explains.

But Fueser’s uneasiness persisted. “There are a lot of concerns about gentrification, too,” she continued. To capitalize on Toronto’s booming tech sector, Google Canada pledged to move its headquarters to a currently undeveloped site adjacent to Quayside. In doing so, she cautioned, “All the housing that would be built would potentially go to the [high-income] workers that [Google] brought with them.” Innovations like Sidewalk’s self-driving trash bins, for example, can destroy public sector jobs. Sidewalk’s reports, however, project that their proposal will create 93,000 jobs by 2040 and promise to promote subsidized housing. The company has declined requests for comment.

When Fueser attended one of Waterfront Toronto’s public consultation meetings in November 2019, she quickly realized that she was not the only skeptic. The briefing began “in this sort of celebratory moment where I think Waterfront Toronto was proud that they stood up to tech giants” on some requests, Fueser recalled. But people were still uncomfortable. “It was an extremely hostile and tired environment, if I could describe it that way,” she said with a laugh.

During the meeting, a sticky note caught Fueser’s eye: “Google has just been accused of violating healthcare laws in the U.S. Shouldn’t that be enough to cancel this project?” After reading it, she said, “It felt like something in the room just snapped.”

The note referenced a federal investigation launched in November into Google’s “Project Nightingale,” an effort to collect health data on millions of Americans. This investigation is merely the latest episode of what has been built up to be a murky track record of the ethical practices behind Google’s handling of user data. Only two months earlier, Google was forced to cough up $170 million to the FTC for selling YouTube ads targeted specifically at children.

With Sidewalk pitching in $50 million out of its own pocket to fund the development, Fueser could not help but question the Alphabet subsidiary’s larger intentions with the personal data it collects. And in the age of Cambridge Analytica, these revelations have Torontonians on edge. “I think that the privacy issues are completely valid,” Mortazavi affirmed. The responsibility, he believes, falls “on governments to set the policy frameworks within which Sidewalk Labs needs to operate.”

***

In response to the concerns, Sidewalk was forced to elaborate on their plans. They stated that their goals are rather simple: First, they want to demonstrate how their innovations will change urban quality of life. Second, they want a “reasonable return” on their $50 million investment.

Sidewalk affirms that all personal data will be stored within Canada’s borders; they will not sell or share personal information to companies—including Google—without explicit consent, and they will not use it for targeted advertising. In addition, they emphasized the absence of all facial recognition technology from their plans.

The company had also responded to mounting criticism from the real estate community when in February 2019, Doctoroff wrote in the Toronto Star that Sidewalk would no longer pursue the role of “lead developer” on the Quayside project. Instead of tackling all 190 acres outlined in the MIDP, he wrote, the company would mainly focus on the 12 acres of Quayside before stepping back to a role as an adviser and investor on future development projects.

Though a powerful public outcry ultimately forced Sidewalk to scale back, Berridge is convinced that Doctoroff will keep the public in Sidewalk’s favor. “To be candid: they managed public opinion [and didn’t just take criticism] randomly,” he said. “They were very sophisticated in that.”

Indeed, a May 2019 poll found that 54 percent of Torontonians support the project after its adjustments and 29 percent are undecided. Mortazavi, for one, trusts that Sidewalk understands that Quayside can’t “be solely their project,” and instead that “they need to act as a partner” with local residents.

***

Amid the crumbling sheds and wired fences that line the Quayside shores, one building stands out: a royal blue warehouse, surrounded by bright yellow picnic tables, a futuristic weather canopy, and some illuminated Dynamic Street tiles in its parking lot. Named “307” for its address on Lakeshore Boulevard East, the building houses more than just Sidewalk’s headquarters. Each Sunday, Sidewalk holds public “open hours” to give Torontonians a glimpse of the future that Sidewalk envisions for them.

Doctoroff’s compromise of “stepping back” could, in Berridge’s view, prevent Sidewalk from turning some of its boldest visions showcased at 307 into realities. “City planning is not architecture; city planning is done at scale,” Berridge said of the circumscribed neighborhood. “If you want to have a private carless neighborhood, which is an opportunity sitting there waiting for us…It makes no sense on a 13-acre site.”

Fueser, though happy with the scale-back, was also dissatisfied with Doctoroff’s decision, given that it fell short of the project’s complete cancellation. “I think [Sidewalk’s got] a foot in the door,” she said. “It’s just going to take a little longer and it will take more work for them to get there.”

Two years and thousands of pages of documents later, whether Sidewalk will “get there”—and where exactly they are trying “to get”—is not perfectly clear. For starters, Sidewalk’s objectives have taken a nearly 180-degree turn over the last three years. A company that was once defined by Schmidt’s 2017 remarks asking for governments to “give us a city and put us in charge” has now evolved into a project in collaboration with the surrounding community.

With a tri-government organization and local urban planning firm holding the reins, Mortazavi anticipates that the biggest innovation that will come of this experiment—beyond Sidewalk’s technological proposals—will be showing the world what a strong partnership between the public and private sectors looks like. “It’s a question of how do you actually develop frameworks to help mitigate that risk and ensure you’re not taking everything on a wholesale and not actually considering what the downsides are,” he said.

At the end of October 2019, Waterfront Toronto’s Board unanimously voted to move the project forward into its formal evaluation phase, a point that Fueser and #BlockSidewalk hoped would never come.

“It’s more like passing through a gate as opposed to getting to the finish line,” Mortazavi said of the vote. “It’s a pretty fulsome process around wanting to evaluate [the] financial and the practical aspects of the solution,” he said. The Board’s evaluation will come in March of this year.

With a project like this, it’s more about process than product. “At the end of the day,” Berridge reflects, “you get innovation by crashing and bashing around and seeing where you get.”