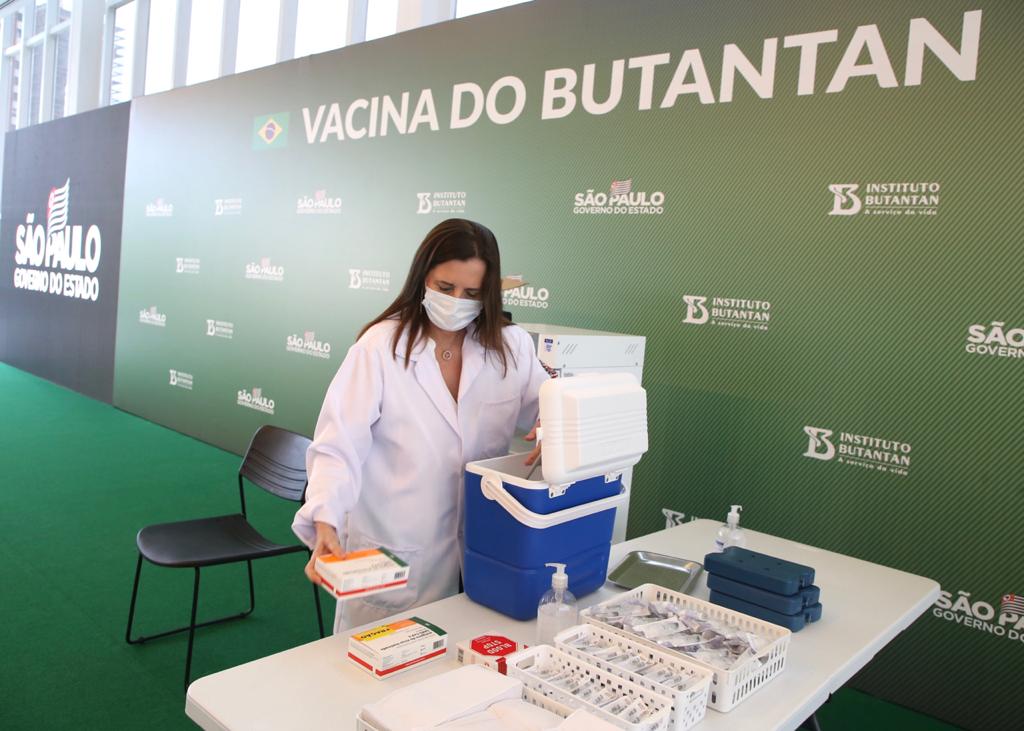

While so many Americans refused to get vaccinated against COVID-19 despite the abundance of available vaccines, in early 2021, Brazilians were scrambling to protect themselves amid vaccine shortages.

Fortunately, despite its slow start, Brazil’s vaccination campaign was a success. As of 2022, Brazil is among the top 20 countries in terms of COVID-19 immunization rates with an overall vaccination rate of 83% (and 95% in São Paulo, the country’s most cosmopolitan city). At the outset of the pandemic, Brazil was working to overcome a myriad of political and socioeconomic obstacles, from food insecurity to worsening social mobility at the outset of the pandemic, but Brazilians stood together to defy a common foe and try to restore a state of normalcy.

Many called the turnaround in the country’s vaccination rates a miracle. Brazil’s president, Jair Messias Bolsonaro, continuously proclaimed his skepticism toward COVID-19 vaccines and portrayed the pandemic as a conspiracy theory rather than a health crisis. “[President] Bolsonaro’s stance fortunately did not impede healthcare workers to distribute vaccines across the nation,” he explained Rio rheumatologist Marcelo Torres Gonçalves. “It did, however, lead to a 30-day delay in shipping as many denialists pushed against the vaccination campaign.”

President Bolsonaro also seriously undermined the legitimacy of the virus by refusing to enforce lockdown procedures across the country in the initial stages of the pandemic, putting millions of lives at risk and widening the social gap in Brazil due to a rapidly increasing unemployment (especially in suburban towns). His opinion, however, did not resonate with most of his followers. “Even when Brazilians felt discouraged and unsupported by the government in most troubling times – January to April 2021 – they remained hopeful that the situation would soon get better,” said Gonçalves.

Despite Bolsonaro’s purely moral anti-vaccination stance, the Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency (ANVISA) hastened to make COVID-19 vaccines available to the public as early as January 2021, leading to the country’s soaring vaccination rate. Brazil’s healthcare system successfully overcame the president’s messaging and convinced around 50 million Bolsonaro supporters to get vaccinated against his advice. But Bolsanaro still remains a relatively popular candidate following his unpopular decisions with almost 25% of guaranteed votes in the upcoming 2022 presidential elections. Bolsanaro is trailing just behind former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who was recently released from prison. Bolsonaro’s continuous and possibly growing support network is the inevitable outcome of a fragile political system that is both very similar and different to America’s.

America’s anti-vaccination movement and its ties to former President Donald Trump is an interesting case study to analyze this political phenomenon. At present, 77% of the United States’ population is vaccinated against COVID-19 with at least one dose – a significantly lower proportion of the population as compared to Brazil. A study at Texas A&M School of Public Health found that approximately 22% of Americans have declared themselves to be “anti-vaxxers.” Initially, it appeared that Trump’s rhetoric had inspired this resistance using similar tactics as Bolsonaro: spreading fake news and calling the pandemic a hoax. However, unlike Bolsonaro, Trump openly shifted his views on the pandemic and vaccination in late 2021, causing backlash from his followers, who continued to defend the anti-vaccination movement. This continued support for anti-vaccination movements despite Trump’s change in opinion indicates the public’s perspectives may not be as easily swayed by political authorities they admire. As suggested by Dr. Gonçalves In Brazil, public opinions on getting vaccinated also turned out to be less malleable than expected; the public reacted unfavorably to Bolsonaro’s policies despite his anti-vaccine rhetoric. In both Brazil and the United States, the nation’s respective COVID-19 vaccination program’s success was not the outcome of the population’s political alignment, but public opinion on scientific beliefs and reasoning. The people just wanted to protect themselves against a lethal virus.

Both Trump and Bolsonaro felt the consequences of their unpopular stance on vaccines, so much that Trump was voted out of office a little more than a year after the pandemic hit. While he still garnered votes from almost 47% of the voting American electorate, Joe Biden’s pro-vaccination policies triumphed in a time of crisis. The results were tight, but the emergence of a mainstream democratic politician had a thunderous effect on the outcome of the elections, ousting the populist former leader.

Though this is where Brazil and America may diverge, such a phenomenon in Brazil is highly unlikely.

Brazilian political affairs are much more susceptible to polarization. The election (and possible re-election) of Jair Bolsonaro is the outcome of a great political and ideological division, and the same applies to Lula. While Lula centers his campaign on increasing the state’s presence in the Department of Labor to attract Brazil’s working class, Bolsonaro promises to tackle corruption to gain popularity among Brazil’s elite, self-sufficient class. Both of these candidates are leading pre-election polls and lie on the opposite extremes of the political spectrum in Brazil: Bolsonaro positions himself as conservative whereas Lula is the national emblem of socialism. Candidates at the extremes of each political spectrum are the result of the deteriorating, passive center parties– often associated with corruption. With the populist appeals offered by both Bolsonaro and Lula’s personas, millions are attracted to their passion for politics. A small portion of the population is strongly supportive of either candidate, and most are torn between both fronts, and very small nuances in their opinions determine who they vote for. The absence of centrist politicians in the upcoming October 2022 elections forces sympathetic voters to choose between two extreme options.

This phenomenon sparked intense polarization as more people began defining their political stance in negative terms, such as “anti-Bolsonarism” or “anti-Petism” (anti-Workers’ Party). While anti-Bolsonarists claim that they are voting for Lula because of Bolsonaro’s racist remarks and slow response to the COVID crisis, anti-Petists characterize their vote as a step towards anti-corruption or anti-socialism. Therefore, voters who hold moderate positions are forced to choose one side based on slight variations in opinion.

But Bolsonaro’s mistakes weren’t enough to change the minds of more than half of his voters. Rather, his sympathizers prioritize adhering to anti-Petism to prevent Lula from rising to power again. This increasingly polarizing society is the product of strong Anti-Petist and Anti-Bolsonarist sentiment. Both ideologies become an identity – an emotional platform for citizens to denounce the flaws of their least favorite candidate. Therefore, despite Bolsonaro’s mistakes, people still vote for him to voice their views against central topics such as corruption and/or socialism, which are embodied by Lula’s campaign. The idea of anti-Petism, therefore, became a tool to unite Bolsonaro’s voters against Lula and the Workers’ Party. Brazilians with views across the political spectrum often find themselves inevitably drawn to anti-Petism, which encourages them to view the opposing candidate in a more negative light. This is why many Brazilians refuse to switch sides at present, despite Bolsonaro’s mistakes while in government.

The friction between Bolsonaro and Lula (or the Workers’ Party) prompted a vicious cycle in which the extremes of politics are always clashing against each other, scrambling to attract the popular vote through moral tactics that interest specific groups of people around Brazil. This is the moment in which all reservations related to pandemic strategy and overall politics become of secondary importance. Brazilians inevitably become engulfed in hateful rhetoric. Even those who hold strong opinions against Bolsonaro’s work over the past four years believe that tackling corruption outweighs having an adequate, scientifically-backed stance on healthcare crises as rare as pandemics. Slight differences in thought result in thundering reactions. Nowhere is this phenomenon more clear than in pre-election street manifestations. The many inflatable figures of Lula dressed in a prison uniform and Bolsonaro wearing Death’s black cloak at these gatherings exemplify that the Brazilian elections are primarily driven by hatred, by ambitions to dissociate a party or ideology from national politics.

As we go forward, we can expect increasing tensions as people take to the streets to protest against Bolsonaro or the Workers’ party. Currently, it seems like we will not see a parallel outcome as in the United States in late 2020, but which side will prevail? Are people ready to re-embrace Petism, or does the memory of Lula’s presidential term bring an unmatched bitter taste to their mouths?