As Peruvians headed to the polls on Sunday, April 11, earlier this year to vote for their next president, the preceding five years of tumult and decay haunted their thoughts. They had seen the country’s aggressive economic growth slow down starting in 2014, and while they continued to outperform their neighbors, the COVID-19 pandemic brought with it the country’s first recession of the 21st century, erasing most of the gains made after 2014. They had seen the rise of four presidents and the fall of three since the 2016 elections, the outcome of a Kafkaesque political game that also saw Congress shut down by executive command in 2019. The third of these presidents, Manuel Merino, lasted only five days and was forced to resign after a wave of mass protests in November, 2020. Two people died and 100 were injured, emboldening all others and promoting direct action. Pretense of political stability long gone, these riots ended Peru’s status as a beacon of social stability, too, in a region tormented by destructive demonstrations. Indeed, less than a month before the first round of voting, strikers blocked both the Pan-American Highway and the Carretera Central, threatening, among other resources, oxygen supplies to treat COVID-19 patients for those who depend on these highways to access the capital city of Lima.

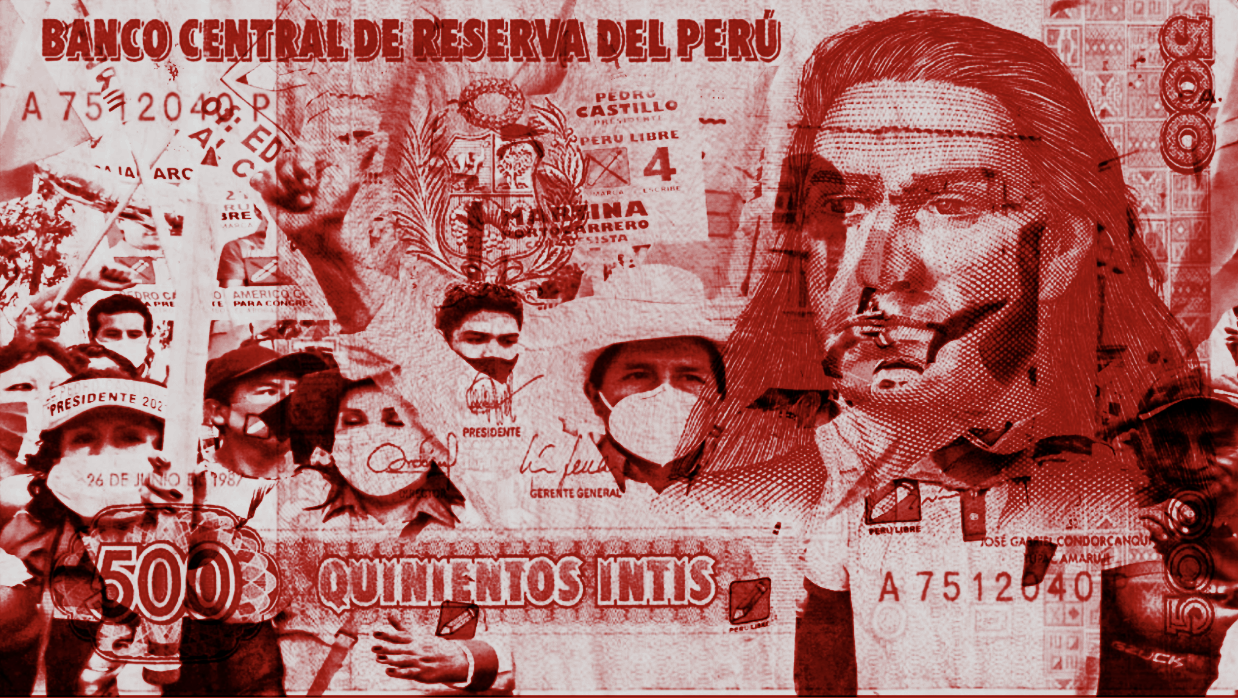

It was in this context that Pedro Castillo, a unionist, schoolteacher, and self-declared Marxist from the Peruvian highlands, obtained nearly 20 percent of the vote in the first round of voting in April, more than any other among the eclectic array of eighteen candidates who opposed him. These included a former football player-turned mayor, an Opus Dei millionaire running on an anti-communist platform, a world-renowned economist once considered for the Nobel Prize in his field, and an education-sector businessman known for promising his political allies, as he liked to put it, “money like popcorn”.

Castillo is now set to run against Keiko Fujimori, the runner-up, in a second round of voting this June. She is the daughter of former president Alberto Fujimori, who oversaw the defeat of the Shining Path terrorists and reconfiguration of Peru’s economy from one of the weakest to one of the strongest in Latin America, but has also been condemned for acts of corruption and human rights violations. The younger Fujimori has long had a significant following but an even more significant “anti-vote.” She was defeated by drastically different candidates in the previous presidential second rounds of 2011 and 2016, and as recently as March 28 of this year, 55 percent of Peruvians polled claimed they would never vote for her, motivated at least in part by her party’s role in the political crisis of the past five years.

Fujimori may well overcome her historical “anti-vote” in light of an unprecedentedly radical Marxist opposing candidate, as Peruvian journalist Augusto Álvarez Rodrich recently claimed. Yet, since moments of institutional crisis tend to amplify calls for drastic change, there remains the possibility that Peru could be governed by a Marxist-Leninist in a few months’ time. An exhaustive look into his party’s 2020 manifesto will reveal just how dangerous this prospect is to the consolidation of a democratic and prosperous Peru.

Links to Violent Revolutions of the Past

The manifesto’s opening chapter embarks on a dangerous historiographical path, claiming that the Peruvian revolution initiated by Tupac Amaru II, has “not yet concluded.” While Tupac Amaru II, a descendant of the Incan nobility, led a revolt in the late 18th century against the Spanish Empire that set the stage for the country’s independence, his image has recently been appropriated by opponents of democracy in Peru, including the Velasco regime of 1968-1975, Peru’s penultimate military dictatorship, and the Tupac Amaru Revolutionary Movement (MRTA) in the 1990s, a terrorist organization seeking to implement a Marxist-Leninist government in Peru. The narrative of the incomplete revolution, therefore, aligns Castillo’s party with a historical delegitimization of democracy—an aspect of their platform that, as will soon be evident, informs their policy prescriptions.

It is also worth noting here that according to the Peruvian Ministry of the Interior, Castillo had established links to the political arm of the Shining Path terrorists during his time as a union organizer. While he has denied these allegations, they remain a significant concern, especially in light of the unapologetically anti-democratic platform he is running on.

Battering Democratic Institutions

According to the aforementioned manifesto, freedom of the press is a bourgeois fantasy. Former dictators Vladimir Lenin and Fidel Castro are both praised for their policies with respect to privately-owned media, and it is explicitly clarified that “socialism does not advocate for the freedom of the press, but for a press committed to the education and cohesion of the people.” The text explicitly attacks traditional media groups El Comercio, ATV, and Latina, accusing them of “extorting the state” through their scrutiny of government policy and claiming that their concentrated influence must “not just be combatted, but prohibited.” While these acts of censorship are justified under the pretext that these groups have long monopolized the Peruvian media scene, the text then advocates for the elimination of what it considers “garbage programming,” more specifically, by mandating that all radio and television content be pre-evaluated by the Ministries of Culture and Education, both headed by members of the president’s cabinet.

Castillo’s party manifesto similarly threatens the integrity of the country’s judicial system. Though far from fully impartial, Peru’s justice system has thus far prosecuted nearly every Peruvian president of the 21st century for their acts of corruption, regardless of their political ideology. The manifesto claims that while Castillo’s party supports anti-corruption policies, as is essential to gain support in Peru’s current political climate, it complains that said policies can also be used as an element of “political persecution, as long as we have a neoliberal judicial branch, for which some precautions must be taken.” While the full extent of these “precautions” is unclear, the manifesto suggests that the separation of powers should be undermined by appointing and potentially deposing high magistrates by popular vote, thus subjecting their decisions to the visceral passions of mass politics. This is an especially concerning point because Vladimir Cerrón, one of Castillo’s most important political allies, is currently imprisoned for proven acts of corruption, a fact that Castillo has denied, claiming that Cerrón has not been sentenced “for corruption, but by corruption,” or, to put it in American parlance, by “the swamp.” The removal of judges through the popular vote, then, could enable Castillo to mobilize his party’s political clout and grant impunity to actors like Cerrón. Even before reaching the presidency, Castillo has revealed his dangerous strategy — to misinform the population, delegitimize existing institutions that stand to curtail executive abuses, and eventually subject said institutions to his will by the popular vote.

Perhaps most deceptively, the manifesto promises a total overhaul of the Peruvian public education system, which would see the introduction of courses in “philosophy, political economy, geopolitics, and art.” All of these subjects, while potentially edifying, can easily be manipulated by narrowing the perspective of all students to the philosophy of Marx, the political economy of Lenin, the geopolitics of Castro, and the art of the Latin American communist movement, for example. Indeed, given the proudly Marxist-Leninist character of this manifesto and its censoriousness with respect to the media, it would be difficult to imagine it meaning anything different when describing an education system meant to raise students who are “honest, autonomous, and revolutionary.”

All of these changes would be pursued through constitutional reform, much like that pursued by Hugo Chávez in 1999 to instate the current constitution of Maduro’s Venezuela. These are all especially unwelcome developments in a country where lasting constitutional government has not been the historical norm. Peruvian democracy as it exists today is only twenty years old, and yet this remains the second-longest period of constitutional rule in Peruvian history, surpassed only by the 28 years from 1886 to 1913. Indeed, the past five years have put the continued fragility of the country’s democratic government on display.

The Return of Revanchist Economics

The economic program of Castillo’s party manifesto is similarly worrisome, promoting drastic and heavy-handed changes to Peru’s economic system in the midst of the COVID-19 recession. Its proposals include the “nationalization of natural resources” and the “return to the state” of vast tracts of land, threatening the security of individual property rights. The “revision of all free trade agreements”—on which Peru has relied to more than double its exports from 2000 to 2019—is promoted, as is the charging of “all kinds of taxes,” suffocating private economic activity at a time when the state sector could not make up for the loss except through prohibitively expensive deficit spending. Though the manifesto simultaneously promotes the total elimination of the country’s foreign debt, Castillo claimed in an April 2021 interview that he was “not in favor of paying the foreign debt,” implying that he would try to get rid of the foreign debt by defaulting on it.

Unlike neighboring Chile, Peru has never had a Marxist president. But most of these policies align with the revanchist economic model pursued by the Velasco dictatorship starting in 1968 and largely left untouched until 1993. As Castillo promises to do, Velasco expropriated large tracts of private land, brought the country’s main industries under state control, and otherwise imposed prohibitively expensive costs on individual initiative, all under the pretexts of collective justice and economic nationalism. Many of these newly nationalized sectors would come to operate at a permanent deficit, contributing to a debt crisis that would haunt Peru throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, causing hyperinflation and increasing poverty to staggering heights.

The economic failures of the Velasco period are well-documented by the Peruvian Institute of Economics. The dangers of repeating them are evident through a simple comparison of Peruvian economic growth during the Velasco and post-Velasco era, between 1968 and 1993, to that of the period between 1993 and 2018. The former model, which Castillo now supports, saw the country’s GDP per capita decline to 82.7 percent of its 1968 level. The latter, which Castillo wants to replace, has seen Peruvian incomes rise to 253.4 percent of 1993 levels.

The difference between these models for average Peruvians, who have also seen improvements along a variety of social dimensions since 1993, cannot be overstated. Twenty-five more years of the 1968-1993 average growth rate, starting in 2018, would reduce Peru’s economic status to that of modern-day Iraq by 2043. By contrast, 25 more years of the 1993-2018 growth rate would lift it to the status of modern-day Poland in the same period. Of course, exogenous factors also played important roles in both periods, so the difference between these models moving forward may be exaggerated by these projections. Yet, given the growing importance of having competitive institutions in a globalized world economy, it may well be understated.

An Election to Define the Next Decades

While Peru’s economic prosperity and democratic life had reached heights not seen in generations at the dawn of the 21st century, it is undeniable that the past five years have brought a series of crises that have challenged the stability of this new order, culminating in the catastrophe of COVID-19. It is at these junctures that the institutions enabling freedom and democracy are tested, and either prove their resilience for generations to come or reveal their fragility as exceptions to the historical norm. Castillo’s candidacy represents the greatest threat to these institutions in Peru for a very long time. In a few months, we will know whether the Andean country can overcome this challenge.