On July 2, 2018, Fan Bingbing, the highest-paid actor in China in 2017, posted on Weibo, a Chinese microblogging website similar to Twitter, about a visit to a children’s hospital in Tibet. That same day, her account went dead. Rumors circulated, as nobody knew what exactly had happened to Fan.

“It’s like if Jennifer Lawrence disappeared,” said Yale political science professor Daniel Mattingly, who studies Chinese politics and governance.

One of the most frequent covert, practices of the Chinese government is arbitrary detention, or the detention of an individual without due process or evidence. The precise number of detainees is vague, since the government does not release these figures. The recent disappearance of Fan and former Interpol Chief Meng Hongwei has sparked international discourse on similar disappearances of Chinese citizens.

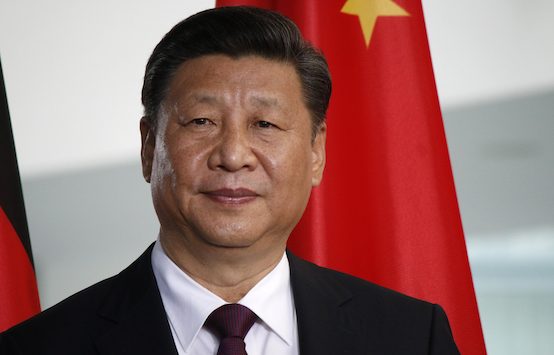

The central figure behind the arbitrary detention policy is none other than Xi Jinping, who became president of China in 2012. Experts speculate that detentions like those of Fan and Meng are part of Xi’s concerted anti-corruption crackdown.

Beginning in the late 1970s, China experienced an economic boom that has pushed it toward becoming second largest economy in the world today.

But Xi wants to make China even stronger—economically, politically, and militarily.

“He calls his vision for the country the Chinese Dream,” explained Yale undergraduate Sally Wang* ’21 from the southern coast of China. “His view is that the current era is the great renaissance of the Chinese people, evoking a sense of shame for the past as a time of backwards poverty.”

As strong as China has become under Xi’s rule, there is a dark side to his leadership. The arbitrary detention of Fan and Meng is the tip of the iceberg. Xi is also responsible for the imprisonment of up to a million Uyghurs—ethnically Turkic Muslims—in “re-education camps” in the western region of Xinjiang, a relentless campaign to marginalize China’s churches, and ongoing repression of human rights workers, journalists, photographers, and academics.

Wang requested anonymity in this article, fearing professional and personal consequences for herself and her family for speaking out on such sensitive Chinese political issues. “I know a couple of cases of students like me being contacted by national security,” she said. “I’m a little worried about my mom,” said Wang, whose mother is a party member and works for the government. “She’s planning to retire in a couple of years.”

The Fan and Meng Puzzle: Putting the Pieces Together

A social media post by TV star Cui Yongyuan in May 2018 sparked a government investigation into Fan’s finances. Cui revealed two separate contracts that Fan had signed for her movie Cell Phone 2. One contract, which was used for taxes, reported that Fan had made 10 million yuan ($1.5 million), while another reported that she had made 50 million yuan ($7.3 million). She disappeared about two months later.

After three months of public uncertainty, Fan resurfaced in Beijing and posted an apology to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and China on Weibo, asking for forgiveness. The statement followed news that Fan would have to pay a fine of 884 million yuan ($129 million) for tax evasion. Authorities revealed that Fan originally owed 255 million yuan ($38 million) in taxes, 200 million ($30 million) of which was considered tax evasion.

“One could say that every bit of the achievement I have made cannot be separated from the support of the state and the people. Without the good policies of the Communist Party and the state, without the people’s love and care, there would be no Fan Bingbing,” she said in her statement.

The details of her case slowly became clear. Chinese media reported that she had been secretly detained without trial in a “holiday resort” in a suburb of Wuxi in the Jiangsu province. The resort has been used to investigate Chinese officials suspected of corruption.

The case of former Interpol chief Meng Hongwei in October 2018 was even more opaque. Meng traveled to China from France to see family. But after a week of being unable to reach her husband, Meng’s wife Grace approached French police.

Only two weeks after he disappeared, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, the CCP’s primary anti-corruption organization posted that Meng was being detained under “suspicion of violating the law.” Just a few hours later, Interpol announced that it had received Meng’s voluntary resignation, without explaining why it considered the resignation of someone secretly detained as voluntary.

“At this point, we have no evidence,” law professor at NYU Law School and Senior Fellow of Asia Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations Jerome Cohen told The Politic about the Meng case. “There seem to be no means, even with strong popular censure at home and abroad, to get the [CCP] to tell us what it’s all about,” he said.

Meng’s case highlights how arbitrary detention is a key feature of Xi’s sweeping and notorious anti-corruption campaign. Xi has used his crackdown to depose countless rivals and to purge the Chinese political system of the culture of corruption that existed in the preceding Hu Jintao era. Victims of the campaign include senior party members like Zhou Yongkang, China’s former chief of domestic security and, just last year, Sun Zhengcai, the party secretary of Chongqing. Zhengcai, once thought to be Xi’s successor, was sentenced to life in prison for bribery.

Some commentators suggest that Xi was likewise trying to send a message through imprisoning Fan, demonstrating to the Chinese populace that the anti-corruption campaign extended beyond the Chinese political elite. Evidently, Xi’s campaign may put any Chinese citizen at risk.

And yet, Fan and Meng are just two of many victims. Cohen and Mattingly see the countrywide trend of arbitrary detention as far more important than two high-profile instances.

“They’re wonderful cases for advertising to the world the fate of millions of people in China who aren’t known at all,” said Cohen, arguing that the two high-profile events bring international attention to the countless other victims of the arbitrary detention policy.

Cohen also noted that Meng, formerly a vice minister of public security, “undoubtedly sent thousands and thousands of people to arbitrary detention himself and was rewarded with a very nice international job for doing so.” Cohen continued, “He was suddenly summoned home and he, too, disappears… some would say that’s divine justice. I would say that’s divine injustice.”

Mattingly likewise cast doubt on how much Fan’s case demands international sympathy.

Because she was evading taxes, Mattingly said, “in a counterfactual world in which Xi Jinping was not in power, the government might have come after her anyway.”

While Fan Bingbing received a lot of press coverage, other arrests are far more troubling for Mattingly, such as those of pro-democracy activists and the embattled Muslim minority population in the Xinjiang region.

Arbitrary Detention: Past and Present

Modern China has a long history with arbitrary detention, even before the regime of Mao Zedong, who Cohen called a “master of mass arbitrary detention.”

“This is not a new phenomenon,” Cohen said. As far back as the 1920s, people were warned not to accept meal invitations from Leninist dictator Chiang Kai-shek, explained Cohen. “Many people never came back from dinner.”

Now, under the Chinese legal system, the police have a wide array of options in arbitrarily detaining Chinese citizens. Through the Security Administration Punishment Law (SAPL), the police can enforce an “administrative punishment” of up to 15 days of detention for a variety of small offenses that are not deemed “crimes.”

An even greater fear is criminal detention—that is, detention under the Criminal Procedure Law (CPL). The CPL was revised in 2012 to give the police the additional power to detain anyone suspected of corruption or violating national security for up to six months, incommunicado and with no access to a lawyer. This form of detention, euphemistically called “residential surveillance at a designated location” (RSDL), was precisely the one used against Fan and Meng, and has been used against countless human rights advocates and political opponents during Xi’s tenure.

Discussing RSDL, Cohen said, “All the police have to say is that we think the person is involved in some kind of national security problem—that can cover just about anything. They don’t have to have evidence or prove it to anybody.”

But often, the party will imprison people without even having legal authorization. In other words, detention can occur completely extralegally—under none of the statutes mentioned above.

“There are cases when the police simply take somebody away, put a hood over their head, put them in the back of a car, take them to a safe house, where they might be subjected to torture and kept for an indefinite period of time” without any formal government authorization or license, said Cohen.

According to Cohen, such detentions have caused enough anger among the Chinese populace that Xi felt the need to put an “official fig leaf” on the party’s otherwise illegal actions. Namely, in 2018, Xi established the National Supervision Commission (NSC) to become the official party discipline and inspection apparatus. He invested the NSC with severe detention powers, distinct from those the police may carry out under the CPL. Mattingly cited the formation of the NSC as evidence of Xi’s “broadening crackdown,” reaching outside the government and the party to private citizens like Fan.

“The power of arbitrary detention has been exercised under successive communist leaders, but it’s much worse under Xi Jinping,” said Cohen. “It’s becoming much more oppressive,” he said.

Xi Jinping: Chinese and American Perspectives

Xi has made tremendous strides to establish himself as the most powerful leader of China in decades. In October 2017, the CCP wrote Xi’s name and personal vision for China into its constitution. Subsequently, his doctrine came to be known as “Xi Jinping Thought,” a direct reference to “Mao Zedong Thought”—another way to describe Maoist political theory. In February 2018—just one month before the end of his first term—Xi had the CCP abolish presidential term limits. The startling move overthrew decades-old norms intended to prevent the rise of another Mao. “It was a kind of ‘crossing the Rubicon’ moment for Xi,” said James Sundquist, a PhD student at Yale studying international political economy.

But the story of China under Xi’s regime is far from simple. Despite being excoriated in international media for expanding his own power and for egregious policies like arbitrary detention, many people living in China still love Xi and support the CCP. Often warmly referred to as “Xi Dada,” or “Papa Xi,” the leader appears on billboards and at bus stops. “You can’t go anywhere without seeing pictures of Xi,” said Dr. Andrew Junker, who is the Hong Kong Director of the Yale-China Association and a sociologist with a regional focus on China.

These perceptions of Xi echoed in my conversations with Yale students from China.

After Wang mentioned her concerns about arbitrary detention and Xi’s regime in general, she said, “I’m grateful for and appreciate the Chinese government.” “Objectively speaking, the government lifted many people out of poverty,” Wang continued. “There are obviously positive sides about the regime—not just Xi, but even people who came before him.”

Mattingly spoke about the tension between how international media views Xi and how the people in China view him. He said that Westerners often focus on the fact that China is an autocracy, and they frequently criticize the restriction of civil liberties.

“It’s almost certainly the case that the party is popular in China,” said Mattingly. “There’s this bigger story of half a billion people being lifted out of poverty into the global middle-class. It’s a story of Chinese rise and rejuvenation,” he said.

Mattingly said that this story of China is rare in Western media because it creates “all kinds of frictions.” In particular, China’s rise to the status of global superpower—a status previously held by the U.S. alone—may have “fueled some of the anti-China writing and thinking among Americans,” he said.

Cohen provided a very different picture. He described the positive perception of Xi and his government among Chinese people as the product of exposure to “highly restricted focused propaganda that gives a distorted image of reality at home and abroad.”

But Mattingly offered another approach. “I think it’s possible to do both—to celebrate the great things that China has accomplished while at the same time not being afraid to call out the Chinese party for doing things that…are wrong.”

The whereabouts of Meng Hongwei remain unknown. His wife has become an outspoken advocate against the Chinese government and insists that he is innocent.

*Names with an asterisk next to them have been changed to protect the identity of the source.