In February 1989, a young woman strode through an exhibition at the Chinese National Gallery of Art. She passed installations by over a dozen artists—Wang Guangyi, Zhang Xiaogang, and Ye Yongqing among them—and an array of paintings, prints, and sculptures that experimented with form and content. She approached an installation toward the back of the exhibition, pulled a handgun from her jacket, and fired two shots into the sculpture.

Chaos erupted as mirrored glass shattered. People ran for the exits, and security guards ran for the woman. Xiao Lu surrendered her weapon on site.

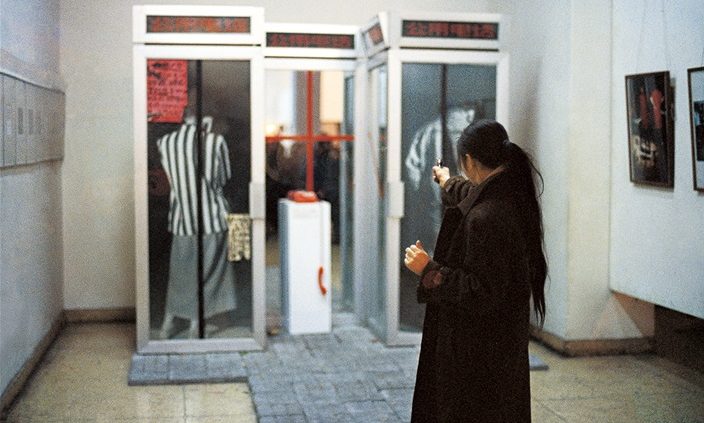

Xiao was an artist, and the piece she’d chosen to assassinate was her own, titled Dialogue. The installation consisted of two glass telephone booths. A man and a woman were shown speaking on the phone, presumably to one another, in separate booths. Above them Xiao had written Chinese words relating to communication. Between the two booths, a red dial-up phone was perched on a pedestal, its receiver unhooked as if someone had dropped it in the middle of a conversation. Xiao had assembled the piece with a fellow artist, Tang Song. On the first day of the exhibition, without clear or apparent reason, Xiao decided to kill it.

She left her actions open to interpretation. Media outlets from around the world tried to contact Xiao, Tang, and other artists associated with the exhibition. The story in most newsfeeds was that Xiao had committed a brazen, highly symbolic act meant to protest the Chinese government’s tight regulation of what works were allowed to be shown in the exhibition. Some artists and counterculturalists in China celebrated Xiao for taking a shot at the authority of the Chinese government.

The government responded with immediate and harsh suppression. It closed down the exhibition and refused to show any more contemporary art there. Demonstrators gathered outside the gallery, part of a larger movement against suppression of creative expression that shook China that spring. In June of the same year, the government famously cracked down on protests in Tiananmen Square, during a day of violence known in China as the June Fourth Incident.

Chinese artists have long imbued their work with political and social commentary. During the Communist Revolution, when most publicly displayed art existed to promote the socialist state, Chairman Mao Zedong said, “There is in fact no such thing as art for art’s sake, art that stands above classes, art that is independent of politics. … Artworks are, as Lenin said, cogs and wheels in the revolutionary machine.”

As China transformed into a Communist state, virtually all public art took the form of pro-state propaganda. Xuānchuán, meaning “dissemination” or “thought exchange,” was propaganda intended to create a cult of personality around Mao and the Communist Party. The use of art as propaganda skyrocketed during the Cultural Revolution.

A transition to laxer censorship policies—ushered in unexpectedly by Mao’s death in 1976, the Sino-Soviet split, and the ascension of Deng Xiaoping as prime minister—accompanied a moderate liberalization of China’s economy. Artists like Wang Guangyi experimented with ideas of capitalism and consumerism. Simultaneously, other artists, like Ai Weiwei and the Stars Art Group, actively protested the government.

This period of emerging political and social commentary in art lasted until 1989, when the government began suppressing free expression again after the violence in Tiananmen Square. Many artists, like Ai, went underground and worked from undisclosed locations. Below the surface, underground art remained highly political, but in public, many artists moved away from overtly political subjects.

Today, the interests of underground and aboveground Chinese artists have continued to diverge, essentially yielding two independent schools of thought. In one camp, artists like Ai Weiwei and Zhao Zhao produce works that protest and criticize the government. Sunflower Seeds, Ai’s most famous piece, is a massive pool filled with nearly 100 million hand-carved porcelain sunflower seeds. The work comments on China’s government-imposed uniformity. Other pieces make their points even more bluntly: one iconic 1995 black-and-white portrait of Ai shows him flipping his middle finger at Tiananmen Square. “If my art has nothing to do with people’s pain and sorrow, what is ‘art’ for?” Ai said in a 2016 interview.

Others approach the question, “What is art for?” quite differently. Cao Fei, a young artist working in Beijing, told The New Yorker in 2015, “Criticizing society, that’s the aesthetics of the last generation. … When I started making art, I didn’t want to do political things. I was more interested in subcultures, in pop culture.” Ideological art, she said, has “all been expressed.” Cao’s art reflects her perspective: her installation RMB City, which appeared at the MoMA’s PS1 show in 2016, incorporates images from Chinese pop culture and Japanese manga.

Cao isn’t an anomaly among young artists in China. In the same New Yorker article, artist Wang Jianwei is quoted saying, “It’s not important that I’m from China. … If art is good, it’s good.” When he spoke about Ai Weiwei, Wang said, “[I] don’t care about him, and don’t care about the media’s worship of him.”

In his work, Wang does not concentrate on Chinese identity, instead focusing on formal qualities such as the use of light, perspective, and form. In 2014, he produced Time Temple, a major installation for the Guggenheim Museum in New York. It is made of massive wood-block carvings and acrylic paintings intended to dismantle and examine the idea of the passage of time.

***

It is certainly safer for artists to avoid politics. On August 3, 2018, Chinese authorities razed Ai Weiwei’s studio, The Guardian reported. By that point, Ai had been arrested numerous times and jailed without formal charges for 81 days. In 2009, he sustained a traumatic head injury after an alleged confrontation with Chinese secret police. But he remains committed to making political art. In fact, he believes there is no way to depoliticize art. “You can escape, you can pretend,” he told The New Yorker, “but if you’re talking about contemporary art, it’s developed through struggles.”

Located in the heart of the West Village in New York City, the Eli Klein Gallery features the work of contemporary Chinese artists, many of whom cannot publicly showcase their work in China. Eli Klein, the founder and owner of the gallery, discussed the importance of politics in Chinese art. In correspondence with The Politic, Klein wrote, “Chinese artists very often use their art to tell stories that can’t be told safely in China verbally or in other contexts.”

The gallery features Chow Chun Fai’s work Painting in Movies. This exhibit portrays cutscenes with matching subtitles from Hong Kong’s New Wave Cinema Movement. Many of the scenes reflect growing repression since Hong Kong’s transition from British to Chinese rule in 1997. In a statement to The Politic, Chow commented, “Artists should blend this concern [about politics] towards the society [with] their creative process. I hope I could bring those cultural viewpoints I value from the ivory tower into the daily life of the public.” His portraits of Chinese citizens act as “allegories,” as he describes them, for broader political anxieties.

Telligingly, at the end of his statement to The Politic, Chow repeated a 1943 quotation from journalist Italo Calvino: L’apologo nasce in tempi d’oppressione. Quando l’uomo non puo’ dar chiara forma al suo pensiero, lo esprime per mezzo di favole.

“In the time of suppression, there are allegories. When a person cannot freely express his own thoughts, he would create fables.”

***

In a 2014 speech to Beijing’s leading artists, propaganda officials, and armed forces representatives, General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party Xi Jinping discussed the role of the arts in China.

“Art and culture will emit the greatest positive energy when the Marxist view of art and culture is firmly established,” Xi said, according to a New York Times translation of his speech. He added, “Some artists ridicule what is noble, distort the classics. … Their work is shoddy and strained, they have created cultural garbage.”

He continued, “What art criticism needs to be is just criticism.” Even so, Xi’s government censored Cao Fei’s piece, RMB City, though its content was not overtly political. Officials objected to the mock Tiananmen Square and a statue of Chairman Mao floating in the sea in RMB City. In response, Cao created a “clean version,” she told The New Yorker.

Chinese contemporary artists frequently return to Ai’s question: “What is art for?” For some, art ought to defend art as an idea, a concept, a vehicle for expression, dissent, and freedom. When Xiao Lu walked into the National Gallery of Art in 1989, she fired what many journalists have referred to as “the first shots at Tiananmen.” They were shots that would echo through Chinese art and politics well into the modern day.