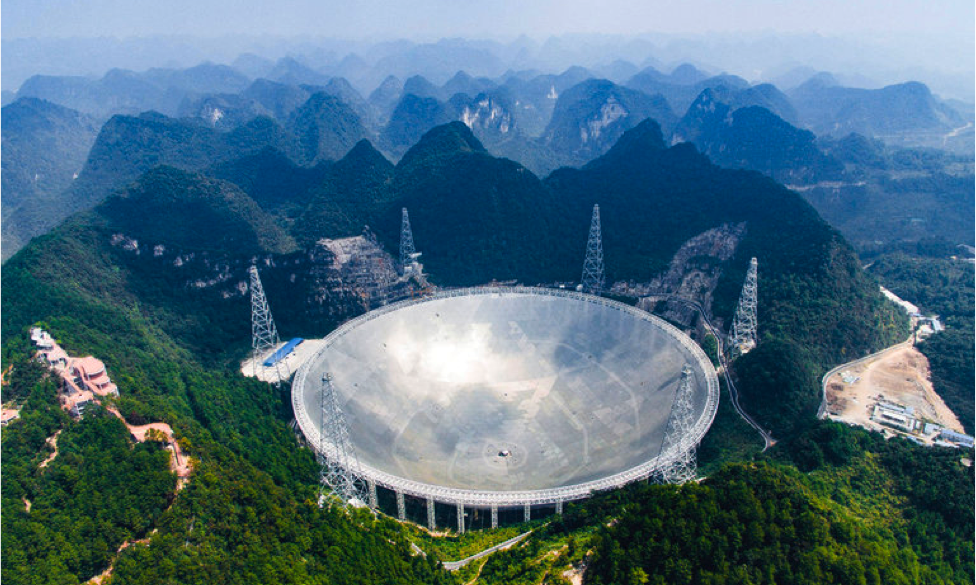

On September 25, 2016, China unveiled its new single-dish radio telescope, making the nation the global leader in deep space and interstellar communication research. The telescope, dubbed the Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope (FAST), is nestled in the foothills of China’s Guizhou Province and is the world’s largest telescope of its kind, with an aperture spanning over 30 football fields that allows researchers to detect signals thousands of light-years away. Construction of the $180 million mega-project started just five years ago, and as President Xi Jinping of China said in a congratulatory message, it will allow the Chinese to “make major advances and breakthroughs in the frontier of science.” The project is just one part of a broader concert of scientific leaps in China over the last decade. These leaps, though gradual, are very strategic and represent an economic metamorphosis that could eventually leave China on equal footing with the world’s most developed economies.

Space exploration is just one domain in which the Chinese government has emphasized investment. In China’s 13th Five-Year Plan (2016-2020), a strategic blueprint outlining the country’s broad social and economic goals, the State Council cut red tape hampering scientific spending in an effort to move away from heavy industry and towards indigenous innovation in research and technology. This surge in R&D spending, an increase from 2.2% to 2.5% of China’s GDP, as well as a transition towards entrepreneurial thinking and venture capitalism will help spark projects in deep ocean exploration, medical nanotechnology, stem cell research, green infrastructure, and mobile telecommunication. China’s emphasis on scientific innovation also means that it will be open to unprecedented global collaboration. The UK-China Centre for Sustainable Intensification of Agriculture launched a cooperative to develop CO2 capture technology, and the United States recently renewed the U.S.-China Science and Technology Cooperation Agreement that will allow over 30 agencies to continue working together to find solutions to the world’s most pressing issues.

As China’s Premier Li Keqiang, the chair of the State Council, stated earlier this year, it is obvious that “[China] is giving top priority to innovation.” So why is a country so historically reliant on mass manufacturing and foreign investment suddenly shifting towards internal development in science and technology?

The answer is simple: China’s economic development has hit a ceiling, and this shift could be exactly what it needs to overcome its current deceleration.

Most East Asian economies follow a simple pattern of economic development: they start by exporting low-end manufactured goods, move towards middle-line manufacturing and exporting while licensing foreign technology, switch to high-end manufacturing and investment, and finally shift to a service economy while sustaining internal development through research and innovation. For years, China’s economy was comfortably centered on manufacturing and investment, acting as an industrial powerhouse for the world’s resource economies and as as the center cog in the larger East Asian supply chain. As of 2015, however, China’s growth slowed to 6.9%, compared to 10.6% in 2010. The implication is that China is approaching a tipping point that will require the country to stabilize its economic development a final time.

In an interview with The Politic, Stephen Roach, a Senior Fellow at Yale’s Jackson Institute of Global Affairs, said that China must “avoid the trap of an aspiring middle-income economy in which technological innovation is stuck” by “shifting [its] focus from manufacturing to services, from exports to consumption, and from import technology to indigenous innovation.”

Developing technology and encouraging scientific exploration are two indicators of an up-and-coming specialized services industry, an economic play that could give China the chance to become a leader instead of a follower. The impact of this strategy is twofold–it sustains a growing consumer and services-based economy similar to those of the United States and U.K. and opens China’s emerging markets to global players. Although the service sector in China is nearly half that of the U.S., it continues to account for an increasing majority of the GDP. The government’s strategy has led to rapid job growth, which means increasing numbers of Chinese citizens are escaping poverty and migrating to urban centers and megacities to take on intensive, higher paying jobs. Migration towards these jobs will improve the quality of life in China over the next several years; however, with more income per capita, Chinese citizens also need a social safety net in order to feel comfortable spending their money domestically. The Chinese government has recognized this need by kick-starting improvements in healthcare security, retirement, and worker’s benefits.

China’s blooming services market not only provides opportunities to Chinese citizens, but also to other service economies around the world. As these economies become increasingly globalized, services also become increasingly tradable for businesses. Stephen Roach observed that other economies may be able to capitalize on such growth, noting if U.S. were to “open up [China’s] markets and trade their services into said markets, there would be an enormous growth bonanza for the world’s largest service economy.” Over the next several years, China’s expansion into this domain is expected to increase the world’s service market by several trillions of dollars. But not all of this development is beneficial to the United States. For example, the U.S. may be forced to find alternative means of debt allocation to continue growth as China’s surplus funds, which are normally sunk into U.S. Treasuries, are shifted to the pursuit of indigenous research, technology, and a consumer economy.

Although most indicators following China’s economic shift are positive, there are some people who receive the blunt end of developmental efforts. Roughly 9,000 Chinese villagers were forced to leave their homes in the southwestern province of Guizhou to make way for the FAST telescope, which requires a three-mile radius of silence to be operational. In return for their pain, each family was given $1,800 of housing compensation. Roughly one million people were displaced along the Yangtze River for the construction of the Three Gorges Dam, and another 350,000 were relocated to make way for the South-North Water Diversion Project. These societal costs of China’s powerful developmental approach do not go unnoticed. Hundreds of thousands of people have participated in mass protests over the last fifteen years, most originating from disputes over land confiscation and environmental degradation. Stephen Roach notes that, “although the government’s strategy is hugely successful…there comes a point when they need to be more conscious of the qualitative aspects of economic growth.” This includes being sensitive to the concerns of citizens and also being aware of the environmental impacts of development, especially in a world gripped by rapid climate change.

China’s ambition is clear: it wants to use its size to become a global leader in research and technology, and in doing so, help create an active economy based on services and consumption. The government’s strategy to trigger a gradual shift is extremely transparent and represents a strategic commitment that could eventually allow them to operate on the same economic, social, and political plane as the United States. Whether exploring deep space through massive telescopes or developing gene-editing tools to combat cancer, China’s influence on science and technology is undoubtedly on the rise. Their research institutions will likely push every scientific frontier over the next several decades, and groundbreaking projects like the FAST telescope and nanotech gene editors will be common. With the government solidifying their intentions, the only unknown is whether they will be able to execute their plan. In coming years, it is essential that China’s leaders restore confidence in their economic model and protect the interests of Chinese citizens. Only time will tell how long it will be until China reaches full economic modernization, but one thing is for certain: the government has taken a creative and bold approach, prompting a shift that could impact the world. As Premier Li Keqiang put it, “When the wind of change blows, some build walls while others build windmills.”