“WHY IS NORTH KOREA SO CRAZY?” flashed word by word in bold letters at the beginning of a Vox video, titled “What made North Korea so bizarre?” While scrolling through Facebook, I paused at the video’s dramatic title and shocking graphics. In two minutes, the piece interpreted one hundred years of North Korean history and stressed the importance of Japanese nationalism to understanding the nation today.

But it was the final slide that stuck with me: a cartoonish depiction of a jail cell with frightened eyes behind its bars. It could have been an image from a Pixar movie. As the credits rolled, I closed the tab.

Vox is a source of news geared toward online consumers. The publication produces content for Facebook and Instagram, posting a mix of “explainer” articles, short videos with bold captions, and data-driven graphics.

Alvin Chang is a Vox graphics reporter whose work involves creating “cartoonxplainers” and diagrams to simplify complex issues for readers. Chang’s recent work includes pieces like “What each incoming president thought was the biggest problem facing America, in one chart” and “A GOP congressman used an extended goat metaphor to criticize Obamacare. We illustrated it.”

Though critics of Vox—such as Patrick Brennan of The National Review—accuse the site of “taking sides” in its explanations, Chang defended the mission of the site as one of reader empowerment.

“The question we ask ourselves,” said Chang, “is how can we, as people who are good at taking in information and communicating it, be on the reader’s side and advocate for them?”

“There are a lot of complex issues that end up affecting everyday Americans, but the deck is stacked against someone who, for instance, wants to understand what is going to happen to their healthcare through the Affordable Care Act,” he explained.

Chang and his colleagues hope to include the average web user in the more sensitive debates of American politics. They frequently address race relations, income inequality and public policy using break-it-down lists or cartoons. Vox’s articles also tend to make bold claims in their headlines like, “Trump’s war isn’t with the media. It’s with facts.” Statements like these can appear like facts instead of opinions, implying that to disagree with the Vox pundits is to sound misinformed. Vox reaches a large portion of its readership through social media sites, like Facebook.

According to the 2016 Pew Social Media Update, Facebook is the most heavily used social media platform for all adults, and the age group most likely to be active on the site is millenials (ages 18-30). Platforms like Facebook have changed the way individuals connect with the press and consume political news.

“Facebook tends to expose us to the kinds of information that the people we are connected to via social networks want to see,” said R. Kelly Garrett, professor of communications at The Ohio State University, who studies emotions and social media.

This means that users are frequently exposed to content liked and shared by friends—the majority of whom often share similar political leanings.

Lauren Lee ’20, shared with The Politic how she uses Facebook to find content.

“I read a lot of opinion pieces or random articles I find that pop up on my feed,” she said. As a political conservative, she said, “the ratio on my feed skews more toward conservative ideas.”

Though most Facebook users tend to see political content that reaffirms their beliefs, much of a given user’s news feed also includes sources that challenge their views.

In a study performed by Garrett and his colleagues at the Ohio State University Department of Communications, most Facebook users were exposed to stories that came from people they disagreed with based on their established ideology.

“A significant proportion—around 30 percent—of stories people interacted with were counter to their core beliefs,” Garrett said.

Twitter has become another popular news source for people interested in keeping up with current events in real-time. Garrett compared different news sources in how they curate what users see.

“A search engine like Google will push us toward things that are popular, or highly cited. Twitter, however, will act like Facebook, in that it’s all about who you choose to follow,” he said.

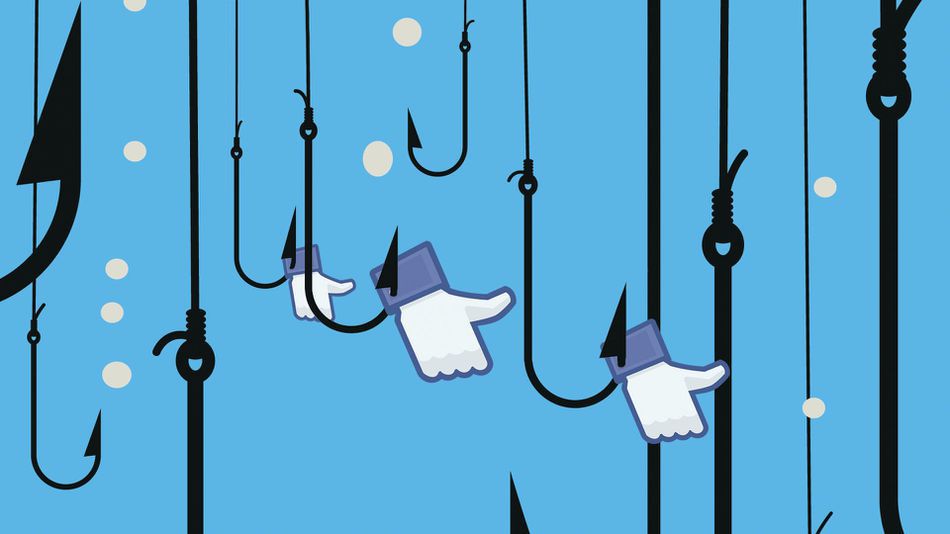

The rising popularity of Facebook and Twitter as well as Instagram and Snapchat as news hubs has generated a demand for more user-friendly content. In an environment where ad revenues and exposure are determined by likes and shares, eye-catching clickbait and graphic-heavy blurbs compete for consumer attention.

“Our millennial generation is notorious for short attention spans, so it’s great that the NowThis video style and other short pieces can keep people engaged who might not be otherwise,” Jacob Bendicksen ’20 told The Politic.

Bendicksen also noted possible shortcomings of simple, digestible news clips.

“But at the same time, a lot of this news is superficial,” he said. “There is more to the key issues than a sixty-second video with some pithy captions.”

Lee added that while she does consume high volumes of content on her Facebook newsfeed, she also visits outside sources for more in-depth coverage of important issues.

“We can’t expect to achieve global citizenship through simplified media content,” she said.

Robinson, himself an editor of a commentary and analysis publication, attested to the downsides of relying primarily on explainers like Vox for information.

“The dangerous thing about Vox is that they’re all about simplifying the news. It’s always, ‘Here’s all you need to know to understand big complicated issue X,’” Robinson said. “It’s a noble role to try and educate the public,” he acknowledged, “but instead of having people understand complexity, they’re portraying the world as extremely simple, when it isn’t a simple place at all.”

The other downside to explainer news media is the bias that necessarily infuses such attractive content. Even where news is not blatantly false, headlines can mislead or distort the facts to fit a partisan model.

“Vox has blurred the distinction between journalism and commentary. Commentary is necessarily inflected with your political positions,” Robinson said. “When you’re doing analysis, you’re not reporting the facts. You are interpreting the facts.”

There is nothing wrong with political analysis. Popular pundits like Bill O’Reilly and Geraldo Rivera attract viewers because they interpret current events in a way people find interesting. They generate valuable conversations in the field of journalism and are distinct from field or investigative reporters. For example, Robinson’s magazine, Current Affairs, deals primarily in analysis of political news, not original reporting.

“I am suspicious of Vox because they portray themselves as neutral explainers of the news,” Robinson said, “instead of what they are—commentators. That’s a great thing to be, but you have to acknowledge your role.”

Vox is considered by many—including Ezra Klein, the company’s founder — to lean center-left. Other content creators like Democracy Now! (short videos and live-streams) and The Other 98% lean even further left, according to the latest data collected by AllSides Bias Ratings. Despite these publications’ detectable biases, Facebook and Internet users continue to like and share content produced by them.

“It’s a funny thing, because I believe the news videos on my feed are trustworthy, even though they clearly have a spin,” Bendicksen admitted. “They’re never nonpartisan.”

New alt-right sources also circulate widely on social media. These sources are known for producing inflammatory content. Breitbart News in particular has gained attention following President Donald Trump’s nomination of Steve Bannon, one of the website’s founders, as chief strategist and Senior Counselor. Breitbart’s website, as well as its Facebook and Twitter accounts, features posts with headlines like “You’re too evil and stupid to know you’re evil and stupid” or “There’s no hiring bias against women in tech, they just suck at interviews.”

From both sides, political discourse on social media sites tends to be partisan and sometimes openly hostile. According to a 2016 Pew Research study on the tone of political interactions on social media, most Democrats (65 percent) and Republicans (64 percent) find it stressful to talk politics on social media. The study also suggested that social media sites allowed people to discuss politics like they never would in person.

“We have really good evidence that Americans view one another with more distrust and more hostility when looking across political lines in general,” Garrett said.

“There is evidence that with the advent of cable news, and the creation of Fox News in the mid-90s, there was a change in political discourse. CNN created an even more dramatic separation. Now there are huge differences between stories told on websites like Breitbart versus the New York Times or Alternet,” he continued.

“People decide what to believe based on the emotions they are experiencing,” said Garrett. “Those who are feeling angry are more likely to accept information regardless of whether it’s accurate or not, if it affirms their political beliefs,” he said.

Mike Isaac, a technology reporter for The New York Times, said that in this new, polarized media ecosystem, outlets have to look for ways to attract readers.

“A lot of folks look at watching or reading the news as something like eating your vegetables,” Isaac told The Politic, “and it’s not very fun—doesn’t taste that good. I respect the idea that you can potentially package quality information into something more accessible. It’s admirable, but I don’t know that it’s realistic.”

To stay afloat in a market where shares and clicks are essential to raising ad revenue, The Times has made an effort to test new forms of content delivery. Some of The Times’s recent productions include “The Upshot,” a data-driven blog addressing controversial issues, and “Daily Briefings,” a subscription service that bring the most important news of the day to the inbox.

“We are starting to experiment,” he said. “People respond very well to explainers. They may look silly, but some of them are reader-service oriented in terms of understanding how to break into a topic. We also do virtual reality and 360 degree video,” he said.

When asked about the promise of The Times’s latest delivery strategies, Isaac responded with optimism.

“I don’t think all of these things will work, and we will fail a lot, but that’s a good thing. The fact that The Times is trying to do different things is a positive. When we find the things that work we will pursue them,” Isaac said. “I’m a believer in the diversification of news sources.”

While traditional sources like CNN or The Times may compete with independent media sites for visitors, there is a role for each kind of content in the news industry. And what Vox and its counterparts lack in complexity, they make up for in accessibility.

“If someone’s first introduction to the war in Syria is through a Vox or NowThis video, my hope is that they could then dig into an investigative piece on The Times or elsewhere,” said Isaac.

But the heated partisanship of the 2016 election has encouraged more users to share news from simplistic and, all too often, untrustworthy sources.

“From a social media platform’s perspective, people are paying attention to what they are paying attention to, and it’s not their role to sort out the truth,” Nathan Robinson, editor of Current Affairs magazine, told The Politic.

Regardless of whether political polarization is a cause or consequence of the kind of content on newsfeeds, the way people engage with news is changing—and so is the consumer’s responsibility in recognizing unreliable sources. Facebook and Google are taking steps to vet deceptive news sources on both of their platforms, though their success so far is unknown. And as more independent media companies produce seductive content that scratches only the surface of complex issues, it will be increasingly important that people explore more nuanced coverage from traditional publications.

After the election, Facebook in particular faced backlash for spreading misinformation. A November Buzzfeed article detailed how fake news pieces — most of which were anti-Clinton — outperformed real news leading up to the election. This outbreak of fake news evokes the “yellow journalism” of the early 20th century. But the internet and advent of simple web design tools have made it easier than ever to create viral and completely false stories that, at first glance, appear legitimate.

Debate about the relative merits of the modern press rages, and hysteria over the rise of fake news continues to grow. But this is no new phenomenon. From grocery-store tabloids that feed on a thirst for drama to Antebellum stories in which slaves were falsely accused of uprisings and violence, the press has long circulated mistruths—including those that serve a political agenda.

“Nothing can now be believed which is seen in a newspaper,” Thomas Jefferson wrote over two hundred years ago. “Truth itself becomes suspicious by being put into that polluted vehicle.”