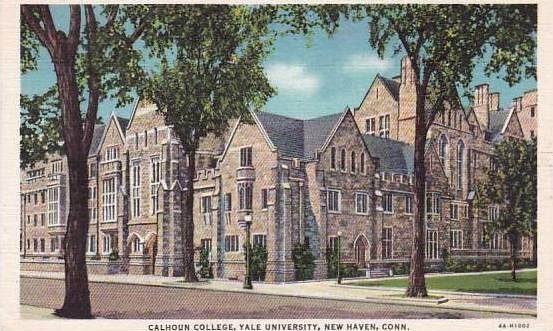

After implementing the residential college system in 1933, members of the Yale administration met to decide on a namesake for the building situated on the corner of College and Elm Streets. William Howard Taft or John C. Calhoun? Due to Taft’s recent passing the previous year, the namers decided to reach further back into history and bestow the honor upon the former Vice President, United States Senator, and Secretary of State. Though Calhoun was an outspoken proponent of slavery and a self-identified white supremacist, the administrators agreed that naming the building after Taft so soon after the president’s passing would be too controversial. On October 16, 1933, the building was christened Calhoun College.

Despite the intention of the namers to avoid a choice that could be controversial, the name of the college was exactly that. Leonard Bacon, a fellow of Calhoun College, read a poem at a dinner to celebrate the opening of Calhoun in 1933. Part of the poem read: “And besides my great-grandfather would turn in his grave, if he dreamed of a monument raised to renown Calhoun in this rank, abolitionist town.” Students raised concerns over Calhoun’s legacy for decades since the college’s naming, and the efforts of the past two years have finally affected change. On February 11, 2017 President Salovey announced the decision to rename Calhoun College to Grace Murray Hopper College, revoking the University’s April 2016 decision to keep the name.

This decision to rename Calhoun College delighted many current Yale students, particularly those who had been active in the #ChangeTheName and #WrongMoveYale protests over the past two years. As the news spread, a spontaneous dance party erupted in the Hopper College courtyard, with pizza, soda, and cookies served in the Head of College house. A student threw snow at a carving of Calhoun’s face, as his name was temporarily covered by tape and replaced with Hopper’s on various signs throughout the college.

“While many students didn’t think the name was going to be changed, I had a lot of hope that they would change it,” said Caleb Kassa, a freshman in Hopper College and a member of the Black Men’s Union. “If they didn’t change it I would have been very critical of much of Yale’s administration, and probably would have been very upset.”

Despite its ubiquity on campus today, the controversy around Calhoun College was not always so apparent. In the eighty-four years that the college held Calhoun’s name, discussions regarding Calhoun himself varied in frequency.

“It wasn’t a topic of discussion,” said history professor Jay Gitlin, ’71. “We just thought that was Yale history. Why would you rename that? It wasn’t about good or bad, or a comment about the person, because we never thought about the person. It was the name of our college. It’s still the way most of us look at it.”

Len Baker ’64 informed The Politic that only one percent of his all-male graduating class were students of color. But nonetheless, Baker recalled that many of his classmates, including former United States Senator Joe Lieberman, travelled to Mississippi for the famous Freedom Summer.

“Racial politics were in a different place in those days,” said Baker. “Civil Rights workers were still being murdered in the South, schools were still segregated, voting rights had not been restored.” Race relations in America were the center of discussion and action for Yale students in the mid-’60s to early-’70s.

“Should change occur?” asked Gitlin. “You can put me down as saying yes. Did we think so back in ’71? Of course we did. But we didn’t think that it was important to discuss the names on buildings.”

As the 1970s progressed, this opinion was not hold unanimously among the student body, and particularly not among students of color. Barry Coburn ’77 was a strong supporter of the name change. “Calhoun was a white supremacist, racist and defender of slavery at a time when there was plenty of available information discrediting these views,” Coburn said. “When a building is named after a person, it is an honor, not a historical footnote.”

Sylvia Madrigal ’79 was even pressured to move out of Calhoun by the student group Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlan (M.E.Ch.A.), because of Calhoun’s racism. “I was at Yale on Affirmative Action as a Mexican American from a small town in Texas. I was completely out of my element,” said Madrigal. “Life was already hard enough without having to deal with a move and all that it would entail. Eustace Theodore, our Dean, encouraged me to ‘assimilate’ and leave all that Chicano radicalism behind.”

After Bryan Blaney ’84 was randomly assigned to Calhoun College, he soon became disturbed with the college’s name. “We knew soon that [Calhoun] had been a slave owner and we made some discussions with the authorities—the Dean and the President—about the fact that he was, and we preferred that our college not be named after someone who was,” said Blaney. “We got no traction. So we didn’t continue to push.”

Blaney informed The Politic that after three months of discussions with the Yale administration regarding changing the name, he and the small group of students—mostly comprised of fellow African Americans—gave up.

Elizabeth Alexander ’84, former chair of the African American studies department, does not remember talk of the name during her time as an undergraduate. However, when she returned to Yale as a faculty member, she noted that there were studies being done by graduate students on Yale’s ties to slavery. “That would have been a useful moment for the administration to amplify and center that conversation in the way that Brown University did,” said Alexander. “But that did not happen.”

The legacy of Calhoun continued to trickle more deeply into campus life and conversation, particularly among students in the college itself. “Even those of us of strong liberal bent were forced to acknowledge that the privileges we enjoyed as Yale students were the product of some of our darker histories,” said Geoffrey Murdoch, ’76. “It wasn’t true of all the other colleges at Yale, but all Hounies left New Haven with a profound sense of knowing how the sausage was made. That name and the stained glass window were in your face.”

Margaret Desjardins ’79, a proponent of a hyphenated name change, as opposed to a full name change, expressed some concern. “Part of me feels that renaming is like editing the ‘N’ word out of Huck Finn,” said Desjardins. “And keeping the thorn in our side, the ‘wound’ open, would have required us to confront and discuss race issues.”

Gitlin worries that future Hopper students will not be connected to the college’s—and our nation’s—past. “You guys will lose a part of your history,” he said. “It will be shallower with this.”

Calhoun alumni have mixed reactions with regard to the way their “Hounie” identities will shift now that their college has a new name. Sharon Agar ’82 does not feel like her relationship to her college will be any different. “My enduring memories of life in what was Calhoun revolve around the people, the physical buildings and place on campus. None of that is changed.”

But for many, even those in favor of the name change, the change is bittersweet. “For us the strong association with Calhoun was about our Yale experience, not about the racial history of Calhoun,” said Baker. “Though many alumni, including me, agree with the decision to rename the College, we are still going to feel a certain sense of loss because in some way it will sever a connection with our Yale identity.”

Desjardins was pleased with the decision to honor Grace Murray Hopper, calling the choice “splendid.” However, she noted that the transition may be difficult: “It will be hard for me to suddenly switch my identity to being a Hopper rather than a ‘Hounie’ after all these years,” said Desjardins. “Perhaps we could be ‘Hoppers—with an apostrophe as a subtle homage to the those formerly known as ‘Hounies.”

Gitlin is saddened by the inevitable separation that will arise between Calhoun and Hopper alumni in future years. “I didn’t go to Hopper. I went to Calhoun. I think it might be the karma of Calhoun-Hopper that it will always represent a divided history,” he said. “It strikes me that we should do whatever we can to heal that rift. So that you and I can have something in common.”

Madrigal never believed the name would change, and was surprised when the topic arose decades after her graduation from Yale. “My experience with white male institutions was that they would always perpetuate the status quo,” she said. “I never for a moment believed that anything would change, and I viewed the long, detailed discussion threads as white intellectual masturbation.”

When she received the news, she was both shocked and uplifted. “In this era of Trump-return-to-whiteness, it seemed like a miracle. There is hope. Even in my jaded, cynical view from years of experiencing discrimination both as a woman and as a minority, I felt a flutter of possibility.”

The name change brings great happiness to many former and current alumni of the college. “I think it is long past due but I’m just glad that it happened,” said Blaney. “I was happy to know that after reconsideration they realized that the feelings of several students were more important than the fear of losing some endowment,” said Kassa.

Alexander was particularly moved by the efforts of students over the past two years. “It was beautiful to see the committed student response last year to changing the name,” she said. “While I once believed you should ‘teach the conflict’ and not erase history with name changing, sometimes history moves beneath our feet.”

For some alumni, the resounding question is: what does the name change mean? On a greater, community-wide level, what will be different? “How does this change who we are in the present?” Gitlin asked. “How does this make things better today?”

Our community will likely continue to grapple with these questions as we move forward, and one of the most well-known controversies in Yale University history is finally put to rest.