This article is based on the interviews and meetings I had during a 11 days YIRA sponsored trip. It took place in Istanbul, Ankara, and Izmir.

IN THE AFTERMATH of the Syrian Civil War, Syrian refugees flooded Europe, creating one of the 21st century’s worst humanitarian crises so far. Perhaps no country has been hit harder by the influx of refugees than Turkey. With a refugee population equal to about 3 percent of the country’s entire popula – tion,Turkey is facing a future of tough decisions and harsh consequences.

This January, I traveled to Istanbul, Ankara, and Izmir, Turkey with a group of eleven Yale students. Our goal was to research the Syrian refugee crisis in Turkey. We met with Cengiz Çandar, a columnist for Radikal and the former Foreign Policy Advisor to the eighth Turkish President, and asked him about the Turkish government’s long-term vision for Syrian refugees. He told us of a meeting in 2011 with president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, in which the president stated, “Over 100,000 refugees is alarming for Turkey.” Çandar continued with a smile, “Do you expect a long term plan from a government that once assumed 100,000 [refugees] was alarming but now houses more than 2 million?”

Çandar writes prolifically about Turkey’s policies on the Syrian Civil War. During our interview with him, he echoed Henry Kissinger, who has claimed that the conflict in Syria is the Middle East’s Thirty Years War. After that long and bloody conflict, the Holy Roman Empire shattered into several independent states. Çandar believes that the civil war in Syria will only end when the region has fragmented into new states.

After almost three hours of con – versation with Çandar, he challenged us to think about the implications of this regional change for Turkey: “Will Turkey itself undergo the same parti – tioning into regions, perhaps based on ethnic origins?”

Only by looking back at the nation-building process, from the Ottoman Empire to the Turkish Republic in the early 20th century, can we understand the fundamental structural changes Turkey faces.

The Ottoman Empire, the precursor to the Turkish Republic, ruled over many different ethnic and religious entities, including Chris – tians, Jews, Kurds, and Armenians. Ottoman rulers quickly realized the challenges of governing such a het – erogenous population. The Ottoman Empire ultimately borrowed the system of millet from previous Muslim nations. Millet gave autonomy to different religious and ethnic groups; the Ottomans only demanded loyalty to their empire. Each millet had its own legal and taxation system. This system worked well until it was threatened by the rise of nationalism within the Ottoman Empire in the 19th Century.

But various groups, especially in the Balkans, began to undermine the millet system and defect from the empire. As a result, Turkey was forced to create a new nation building framework. Some suggested unifying the empire around a Muslim identity. Others suggested relaxing millet and distributing more autonomy to the individual regions. During this period of transition that the Ottoman Empire entered the Balkan Wars in 1912 and 1913 and, in what turned out to be its final war, World War I. After World War I, the Treaty of Versailles partitioned the Ottoman Empire into various nations. In the empire’s ashes, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, a former Ottoman lieutenant, led the Turkish people in the 1919 Turkish War of Independence. On October 29, 1923, he founded the Turkish Republic.

The most crucial question was how to build a nation. According to Ahmet İcduygu, Director of the Migration Research Center at Koç University in Istanbul, Ataturk wanted to keep the Turkish population homogenous. When we started our conversation, Professor İcduygu immediately argued that all discussion around refugees in Turkey should be part of the broader framework of the Republic and what it means to be Turkish. For him, Syrian refugees and their issues are not new to Turkish politics, as Turkey has been dealing with refugees since its inception. However, Syrian refugees represent a unique challenge because Ataturk’s framework cannot accommodate those who do not fit the traditional definition of Turkishness.

Ataturk re-invented the meaning of Turk, formerly understood as an ethnic group. Instead, any Turkish citizen, regardless of his or her original ethnic identity, would be considered a Turk. This was in stark contrast with the Ottoman Empire’s pluralist approach to its populace.

Professor İcduygu, said “Ataturk and his advisers used Turkish identity combined with a culturally religious tone as a cement to form the society.”

Although Ataturk and his advisers were deeply secular, they also concluded that the country had to adopt Islamic culture, a process which happened with surprising efficiency. Professor İcduygu said, “There were officially 260,000 non-Muslims in Turkey in 1936. Today’s Turkey has less than 100,000 non-Muslims. By the pattern of demographics, it should have been 2 million by now.” He speculated that many non-Muslims have left or been converted to Islam in the process of nation building.

On the ethnic front, Ataturk’s government also worked effectively for a homogenous society. The 1923 population exchange between Turkey and Greece ensured the exodus of Greeks from Turkey and the influx of Turks from Greece. In total, 2 million people (around 1.4 million Anatolian Greeks and 600,000 Turks in Greece) were involved in the exchange. Next, in line with the goals of a homogenous society, Turkey passed the 1934 Turkish Resettlement Law. The law infamously legalized the re-arrangement of minorities (e.g. Kurds) into majority Turkish communities for assimilation purposes.

The 1934 Turkish Resettlement Law originated Turkish refugee policy. It allowed only persons of “Turkish stock” and “those attached to Turkish culture” to be accepted into the country. Although now defunct, the law set “Turkish descent” as a key factor in refugee acceptance. More tolerant later laws, like the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 additional Protocol on the Status of Refugees were ineffective in breaking the 1934 law’s legacy. İcduygu concluded that immigration policies in Turkey have been slow to recognize the influx of people who fall outside the parameters of Turkish descent and culture.

This reluctance to adapt is no mistake, but the government’s conscious effort to maintain the ideology of Turkishness. The starkest example of this policy manifested in Turkey’s adoption of the 1951 Convention with “the geographical limitation” that continues to allow Turkey to not take responsibility for refugees coming from outside the Council of Europe. To this day Turkey excludes people of Middle Eastern or South Eastern descent from applying for refugee status, even though they form the majority of immigrants.

Even before Syrian refugees came to Turkey, the ideology of Turkishness failed another minority ethnic group. Kurds, forming between 16 and 20 percent of the population, are the largest ethnic minority in Turkey. They are not ethnically Turks, but the government has attempted to include them in the Turkishness since its founding. However, efforts to integrate the Kurds created backlashes as early as two years after the founding of the Republic. The Sheikh Said (a Kurdish cleric) rebellion of 1925 was an attempt to win some degree of autonomy for the Kurdish population. The revolt was crushed by the Turkish military. In response to the uprising, Turkey issued a law in 1927 allowing the Turkish government to forcibly relocate 1400 Kurds to western regions to be assimilated. Later Kurdish revolts in Ararat in 1930, and Dersim in 1938, were similarly crushed by the Turkish military. The reports of civilian deaths in Dersim range from 50,000 to 100,000 making it one of the bloodiest episodes in the history of the Republic.

Kurdish frustration with the Turkish government’s unwillingness to recognize their history, culture, language and folklore came to a head in the late 1970s, resulting in the creation of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (Partiya Karkerên Kurdistan or PKK)—an organization recognized by NATO and the European Union as a terrorist group— which aimed at countering the government’s forces at the local level.

Over the last four decades, PKK and the Kurdish question have remained major unsolved issues in Turkey. While there are many reasons for this inaction, nationalist ideals are the main culprit. Kurds and their mostly justified demands, such as recognition of the Kurdish language, have gone unanswered because they do not fit into the Turkishness framework. This framework has never been reshaped to accommodate the Kurdish people.

Today, Eastern Turkey is still a scene of war between the Turkish military and Kurdish guerillas. According to Turkish military, since July 2015, 3,953 terrorists and 393 members of security forces were killed in the conflict. The Kurdish problem is a bitter reminder of the failure of the Turkish nation-building framework, and the reluctance to change it in the face of evolving challenges. Given the fact that Turkey now harbors close to 3 million Syrian refugees—all of whom who seem likely be staying permanently— history may be repeating itself.

Merve Ay, the head of the International Alliance of Doctors of Istanbul, believes that refugees do not fit into a preconceived vision of Turkish society. She jokingly mentioned, “We called Kurds Mountain Turks for decades, but re-labeling them did not work. There is no denial that Syrians are Arabs, even if we try to call them Turks.”

Syrians will have to be a part of Turkish society in the future, but how they will fit into the nation-building framework is harder to answer. Will Turkey be locked in a total war with another minority in the future? The current government’s efforts to fight Kurdish separatists are in predominantly Kurdish cities. A similar issue seems poised to arise in cities where the Syrian refugee population is increasing. Kilis, a city in southern Turkey, now houses more Syrians than native Turks. What kind of integration policy is needed to not repeat the mistakes of the past? Syrians are still not recognized as refugees, but as temporary asylum seekers in Turkey. Although they have been granted working permits, most recently in late January, these permits restrict employment to cities where Syrians are registered. Unfortunately, Syrians are mostly registered in cities that already have high unemployment rates, and cannot relocate to other cities in order to find jobs. Education is limited to the few who can speak Turkish. Health service is sorely lacking with “only four pharmacies serving almost a million refugees in Istanbul” said Merve Ay.

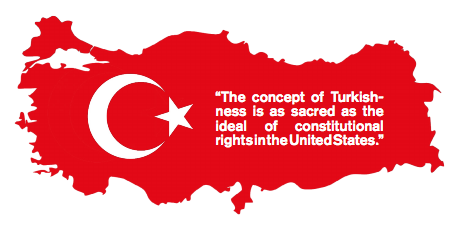

Turkey needs to change the nation-building framework, but what can this essential element of the Turkish identity be replaced with? The concept of Turkishness is as sacred as the ideal of constitutional rights in the United States. Perhaps a new constitution is exactly what the Turkish people need, one that recognizes a person’s contribution to the nation, rather than his or her bloodline, as the token of citizenship.

Turkish citizens of the current generation will have to answer many difficult questions in the coming decades. As Syrians become more permanent members of Turkish society, this generation will have to confront deep racism and crippling xenophobia. With the Kurdish question remaining unresolved for 40 years, Turkey’s record does not yield to optimism. One can only hope for the creation of a more tolerant, pluralistic Turkish society. For that, the country needs to immediately recognize the ticking bomb represented by Syrian refugees, and the shortcomings of the rusty old Turkish nation-building framework.