In the spring of 2014, a French journalist working under the pseudonym “Mélodie” received a private message on social media from Abou-Bilel, a senior commander of ISIS in Raqqa. The journalist, Anna Erelle, had spent over a year writing about European jihadis fighting for ISIS. She had created social media profiles under the name “Mélodie” to investigate why European teenagers might leave the West to fight for the Islamic State. “Mélodie” had only been online for a few days, but she had already attracted a wide circle of friends who fought for or sympathized with the Islamic State. “Mélodie” shared videos and posts about jihad, including a video Bilel had made urging true believers to emigrate to areas controlled by ISIS.

Erelle was stunned at how easily she had made contact with a top commander in the terrorist organization. Over the next month, “Mélodie” spoke often with Bilel, via social media, text message, and Skype. Bilel proposed marriage and provided instructions for “Mélodie” to join him in Syria.

Erelle’s fictitious “Mélodie” is eerily similar to hundreds of Western girls who have fled their homes to join ISIS. A recent report from New America, a nonpartisan think-tank in Washington, D.C., estimates that 4,500 Westerners have left home for ISIS or other jihadist groups in Syria and Iraq. Of those 4,500, one in seven are women, and of the 250 Americans who have attempted to join ISIS, one in six are women. A disproportionate number are teenagers.

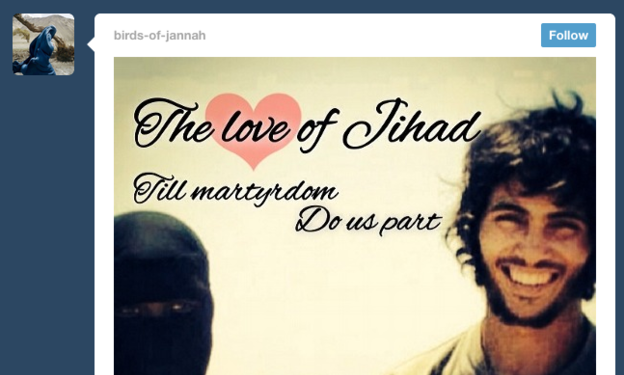

Most women who choose to join ISIS or other jihadist groups are the victims of aggressive and deliberate propaganda campaigns. ISIS’s alleged goal is to build a lasting Islamist utopia, and women are essential for the creation of such a society. It is this vision of a utopia that appeals to many young Western women. A small but active group of women on social media who claim to be living in the Islamic State market ideas of sisterhood and adherence to conservative principles. Websites like Ask.fm and messaging applications like Kik enable would-be recruits to talk to women in Syria, asking questions and seeking advice. Women on websites like Twitter and Tumblr offer recommendations for those hoping to come to Syria (bring a hair dryer, warm clothes; don’t worry about coffee or tea, as they are easy to find).

Female recruiters’ male counterparts, men like Abou-Bilel, appeal to Western women from another angle, flattering potential recruits with promises of marriage, power, and wealth. Women in jihadist groups are depicted as “lionesses,” working with men to build an Islamist utopia. Young girls, sometimes experiencing natural teenage uncertainty about their own futures, are drawn in by promises of an idyllic community and stable families. Jaelyn Young, a 19-year-old American who was arrested on suspicion of attempting to travel to Syria to join ISIS with her boyfriend, wrote to FBI agents she thought were members of ISIS, saying, “I cannot wait to get to Dawlah [ISIS territory] so I can be amongst my brothers and sisters under the protection of Allah swt to raise little Dawlah cubs In sha Allah [God willing].”

Western governments rely on intelligence and watchful policing to stop citizens from traveling to join ISIS, but the potency of targeted propaganda and the anonymous freedom of the Internet make jihad’s ideological lure difficult to combat. Some women seeking to travel to Syria are arrested. Others, like Erelle’s fictional “Mélodie” who abandoned her plans en route to Syria, turn back. Some make it to Syria.

In spring of 2014, Erelle published her first expose of Abou-Bilel, rife with previously unknown information about the inner workings of the Islamic State. Barraged with threats, she has since moved from her apartment and changed phone numbers twice, and she receives personal protection from the French police. “Anna Erelle” is, in fact, not her real name, but rather the second pen name she has used.

Despite the ways in which the project changed her life, Erelle values the insight she gained into ISIS’s recruitment and was able to share with the world. Given the choice, she says, she would do it again.