I woke up one week ago to a slew of text messages that my blind, barely-awake eyes made out as having more rainbow emojis than actual legible text. But I didn’t need to know the words to know their meaning. The judicial pot of gold at the end of the rainbow was the national legalization of gay marriage. Even before the coffee kicked in, I had an excuse to literally skip around the house, triumphantly beaming the way one does when a weight has been lifted off their generation’s collective shoulders. By mid-morning, however, a more bitter thought entered my mind:

“Geez, it took look enough!”

The life cycle of social movements suggests a pattern: grassroots activism from within a marginalized community, compassion of the greater public, community organizing and legislative action, and eventually the acknowledgment of the issue as a matter of fundamental right. As Anthony Kennedy poetically declared in the majority decision: “The dynamic of our constitutional system is that individuals need not await legislative action before asserting a fundamental right.” Many of us knew this momentous decision was coming, that it was time for gay marriage to become a right. The court’s decision wasn’t surprise, but relief. Yet with it nagged the question: why such a long wait?

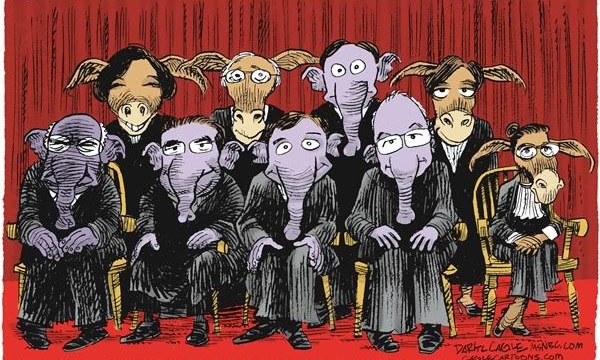

Given that this was a split decision (5-4), perhaps the key to the puzzle lies in the less-publicized side: the nearly half composition of the court who voted no.

So I began my search for clues by reading the justices’ own reasoning. What I found was a 103-page monster decision in which the word count of the four naysayers vastly outweighed that of the winning side. The scathing dissent was so passionate, all four dissenting justices each published a separately-authored condemnation of the majority opinion. They decried the decision as “egotistic,” “pretentious,” and a “distortion of our Constitution,” not to mention Justice Scalia’s dramatic warning about this nascent “threat to American democracy.” To a supporter of gay marriage reading this on a day of profound and widespread celebration, this sort of language and the overall argumentation seemed almost other-worldly.

Take, for example, Justice Thomas’ musings on the concept of “dignity”:

…human dignity cannot be taken away by the government. Slaves did not lose their dignity (any more than they lost their humanity) because the government allowed them to be enslaved. Those held in internment camps did not lose their dignity because the government confined them. And those denied governmental benefits certainly do not lose their dignity because the government denies them those benefits. The government cannot bestow dignity, and it cannot take it away.

So Thomas argues that because dignity is innate, the government plays no role in it, and gay marriage cannot be legalized on such grounds. This argument seems alien to anyone (dare I say everyone?) who understands that equality and mutual respect is necessary for dignity. If slavery doesn’t threaten dignity, what in the world does?

More upsetting, however, was Chief Justice Roberts’s opinion. Roberts believed gay marriage wasn’t a Constitutional issue, writing:

Understand well what this dissent is about: It is not about whether, in my judgment, the institution of marriage should be changed to include same-sex couples. It is instead about whether, in our democratic republic, that decision should rest with the people acting through their elected representatives, or with five lawyers who happen to hold commissions authorizing them to resolve legal disputes according to law.

This was the core argument around which all of the dissenting justices’ opinions orbited. They rejected the court’s role in gay marriage while leaving the door open for legislative action. There was much praise for the “democratic process” of politely convincing peers to adopt your idea. Scalia claimed in his version that “public debate over same-sex marriage displayed American democracy at its best” and warned gay rights advocates that “they have lost, and lost forever: the opportunity to win the true acceptance that comes from persuading their fellow citizens of the justice of their cause.” Justice Roberts extolls the political process as one in which even the losers “at least know that they have had their say, and accordingly are—in the tradition of our political culture—reconciled to the result of a fair and honest debate.”

I laughed out loud when I read this. A “fair and honest debate”? Is that what we’re calling the current state of affairs in Congress and in statehouses across America? I struggle to imagine that the authors of the Constitution would find today’s legislative government to be particularly democratic. And dare we kid ourselves about the humanity and decency of the debate around gay marriage? Fundamental constitutional rights are not to be played with, yet in the modern era corporate fat cats puppeteer politicians and seem to bat constitutional rights around like cat toys. The “factions” the founders worried about have bifurcated the nation past the point of communication.

And this is why we have the Supreme Court. It was created because the founders knew that some rights would have to be safeguarded beyond the rollercoaster of legislative politics and public opinion. The body was meant to elevate the level of discourse about the most important issues of our time, to step in for issues like civil rights in which the public debate will be messy and legally baseless. The Supreme Court exists to put its foot down when it comes to fundamentals. And history tells us that judicial conservatism often conflicts with the intellectual impetus that has brought us protections for women and minorities. For the dissent to decry this judicial power is to pull the brakes on societal progress.

Reader, not to whiplash you too badly, but this is why you must vote in 2016. It is likely that two or three Supreme Court justices will retire during the term of the next presidency. Since the president appoints the justices (and therefore selects their judicial leaning), the next president will decide whether or not to unleash the floodgates of judicial progress. And I hope I have made the case that this progress is contingent on this president’s liberal activism, a judicial persuasion that no one in the Republican cacophony of candidates espouses. If you want more sweeping decisions like this one, you have to vote for a party that leans forward towards them. I don’t care if you prefer Bernie over Hillary or vice versa. Come November, regardless of whose Democratic name is on that ballot, you have to turn out. Imagine you are voting directly for the court – even directly for decisions like the gay marriage case.

I dream that the American human rights forecast includes more rainbow moments like this one. Issues like campaign finance, environmental protection, and gender identity weren’t explicitly mentioned in the 1787 Constitution, and we need a Court now that knows that these issues are deeply tied to the fundamental protection of “liberty” this document promises, a court that speaks America’s moral language. In an era in which Senators are reading from Green Eggs and Ham on the floor and literally throwing snowballs in a fit of “science” (and in which gerrymandering means that government will be in these folks’ hands for a while), the Supreme Court is the best shot we have at moving society forward. And while critics say it is one of the more undemocratic bodies in America, come 2016, it will be squarely in your voting hands. On Friday you may have felt like a passive partier. On an election Tuesday next fall, the ball will be in your court.