As a teenager growing up in Austria, Veronika Denner heard that the pain she felt “every single second of every single day” was simply something she had to endure. Denner graduated from Yale in December 2023 and is an endometriosis activist working with the Germany-based advocacy group End Endo Silence. For years, she confronted the same clear-cut narrative: that to live in a female body is to accept and withstand pain, no matter how unbearable, no matter how perplexing.

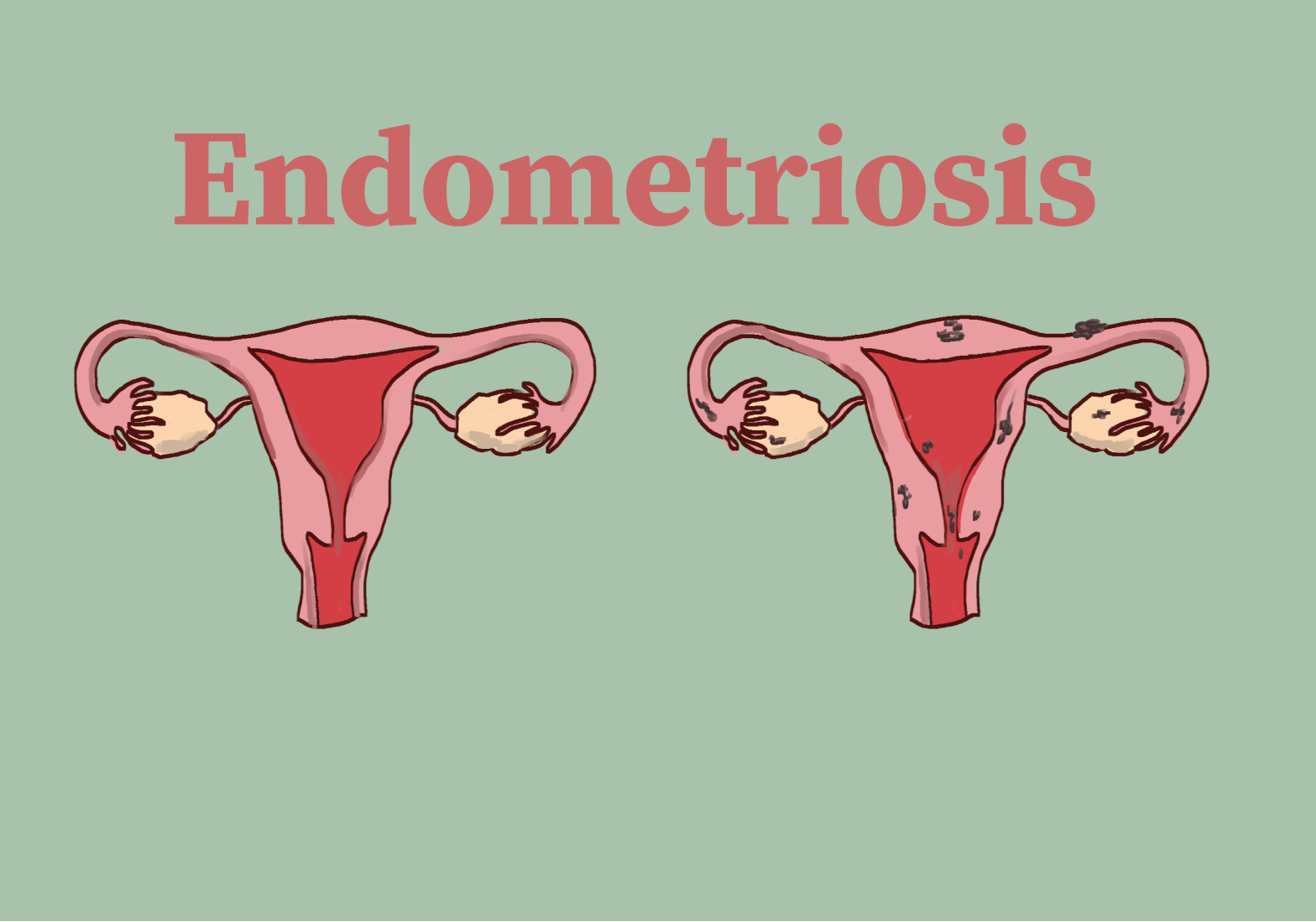

Denner’s story reflects a reality faced by approximately 200 million individuals worldwide: the reality of endometriosis, a chronic disease in which tissue similar to the type that lines the uterus grows in other parts of the body. Endometriosis causes excruciating physical symptoms, including chronic pelvic and abdominal pain, heavy bleeding and severe pain during menstruation, pain with bowel movements and urination, bloating, nausea, pain during sex, chronic fatigue, and, in 30 to 50% of patients, infertility. According to Denner, the disease can also cause bowel obstruction, kidney failure, and, in most severe cases, lung collapse.

Denner had already experienced severe menstrual problems, digestive and urinary symptoms, and pain in her ribcage before coming to college, but these struggles intensified during her first semester at Yale.

“In December 2021, my symptoms deteriorated so much, I was just crying 24/7. I’m not sensitive to pain at all, but I just felt like I was dying. It just felt like something was eating up my body from the inside,” Denner said in an interview with The Politic.

These symptoms forced Denner to take a leave of absence during which she received a long-awaited surgery in Romania. Although the surgery relieved some pain, “the feeling of barbed wire eating up [her] ribcage and upper abdomen” remains a constant, everyday sensation.

For years, when describing her pain to doctors, Denner encountered dismissal, rejection, and disbelief.

“There were doctors that said I just couldn’t handle the academic stress of Yale, even though I had a 3.97 GPA,” Denner said. “There were doctors saying that I was simply depressed and anxious. There were doctors who were like, maybe there is some physical cause to your pain, but you like exaggerating, and that’s why you feel it so much.”

Despite being one of the most common chronic illnesses in the world, endometriosis remains downplayed, misrepresented, and misunderstood. The average time of diagnosis is 8.6 years. Not only do patients endure the physical effects of the disease itself; they confront, in the healthcare system and the world beyond, deep-rooted stigmas that represent female pain as inevitable and insignificant.

***

“Like many other young girls, I grew up with excruciating period pain, which I just couldn’t really bear. But I also couldn’t really get to the bottom of it. So everyone around me told me it’s normal that you feel that way. And it’s just womanhood,” described Anna Moors, an undergraduate student at Zeppelin University and an activist at End Endo Silence.

Moors faced stigmas against female bodies while growing up and suffered a particularly traumatic incident as a teenager.

“I went to school, I lost consciousness, I got extreme heat waves. I was not able to speak, I was basically laying on the ground during a session and my teachers didn’t really pay any attention to me. They were like, ‘Okay, I guess that’s normal. I guess that’s what she does,” Moors recounted. “That continued for two whole hours until I went to the teacher’s room and got a teacher to drive me home. But no one offered to call an ambulance, which is free in Europe, so no problem there. And no one offered to get me medical attention.”

Whether at school or at the doctor’s office, Moors saw her pain constantly overlooked. “I was told that it’s normal, that I’m exaggerating, that maybe I wasn’t eating quite right,” she said. She finally learned about endometriosis for the first time around the age of 18, following years of pain and confusion.

For Arleigh Cole, a Connecticut-based endometriosis activist, the journey towards a diagnosis has been a remarkably long struggle. “It took me 24 years to be properly diagnosed. So throughout the majority of my life, I sort of didn’t know what was going on with my body, and I never felt right,” Cole told The Politic. “I had to sort of start advocating for myself, and I went from doctor to doctor to doctor, all at Yale, for about 11 and a half, 12 years.”

After receiving a diagnosis following decades of confusion and suffering, Cole decided to share her story on social media. “I started sharing my journey on Instagram about six years ago before I went to have excision surgery,” she said. “And at that point, I was like, I’m gonna start documenting this to hopefully help other people because I know I’m not the only one.”

Denner, Moors, and Cole all claimed that when navigating their way towards treatment, there was no better resource than the support of fellow endometriosis patients, many of whom they first met through online platforms like Arleigh’s Instagram profile.

“I think the most support I ever received definitely was from other patients within this whole activism environment of different women and non-binary people who had the same struggles,” Moors said.

Facing a healthcare system and society replete with enduring prejudices against female bodies and a jarring lack of resources for endometriosis research, patients have formed communities to sustain one another. Today, these communities stand both as testaments to patients’ resilience and as warning signs to those in power, signs of a movement that will continue to demand care and recognition for a disease that has till now been confined to silence.

***

Although endometriosis has been around for centuries and continues to impact hundreds of millions of lives today, a startling 75.2% of patients have been misdiagnosed with another condition. The disparity between the prevalence of the disease in the real world and its underrepresentation in healthcare sheds light on broader biases against female bodies in the history of scientific research.

Dr. Noemie Elhadad, professor and chair of Biomedical Informatics at Columbia University who specializes in endometriosis research and is a patient herself, contextualized this disparity in terms of the medical system’s paradoxical understanding of female bodies.

“There’s this double whammy about women in healthcare,” Elhadad explained in an interview. According to Elhadad, the “double whammy” rests on two conflicting assumptions: “one, there are sex differences in health, so women are not represented in research because they’re considered very complicated physiologically. At the same time, they’re considered very simple and like men, and so why bother studying women because men are the default.”

This fractured, incoherent conception of female bodies has led to severe misunderstandings of diseases like endometriosis. In the words of Elhadad, “doctors and nurses and clinicians in general are not equipped to recognize endometriosis, let alone manage it.”

A further hurdle contributing to the lack of endometriosis research is the assumption that any issue affecting female bodies must be tied to fertility. By envisioning the problem through the prism of reproduction alone, this assumption has led to an extremely narrow understanding of the implications of endometriosis. Endometriosis lesions can extend far beyond the reproductive organs and impact all areas of the body, from the pelvis to the lungs, from the kidneys to the diaphragm.

According to Denner, this flawed vision of endometriosis as a purely reproductive disease contributes to the fact that 100,000 hysterectomies, or surgeries that remove the uterus, are performed each year on endometriosis patients, with a 62% recurrence rate of pain. Denner called this “a very medieval and barbaric way of reducing menstrual pain,” since it reduces endometriosis to a matter of reproductive dysfunction and resorts to drastic measures of relatively low effectiveness instead of carefully considering the complexities of the disease.

Dr. Dora Koller, a postdoctoral fellow at the Yale School of Medicine and an endometriosis patient who remained undiagnosed for 15 years, wrote in an email that “although infertility is a serious issue in many women living with endometriosis, endometriosis also severely affects our quality of life. These effects were not considered for a very long time.”

Koller’s research strives to shed light on these overlooked effects by examining the impact of endometriosis on patients’ mental health.

“Endometriosis should be looked at as a chronic systemic disease with manifestations in the whole body, including the brain,” Koller explained. “As my primary field is psychiatry, I was thinking of trying to make the connection between endometriosis and mental health.”

By investigating the link between endometriosis and mental health complications such as eating disorders, anxiety, and depression, Koller and her team sought a holistic understanding of the disease. According to Koller, this holistic approach serves as a necessary antidote to the deep-rooted biases that equate female bodies with the reproductive system alone.

Koller’s main hope in her research is that “our and future results in the topic will motivate medical professionals to screen for mental health comorbidities when diagnosing and following up endometriosis symptoms.”

Elhadad echoed Koller’s call for more comprehensive screenings of endometriosis by doctors. “Patients are not a homogeneous body. Patients have different values,” Elhadad said. According to Elhadad, this heterogeneity should encourage doctors to listen to patients’ distinct experiences rather than rely on standardized measures alone.

“I learned recently that the question ‘how much pain are you in from 1 to 10?’ was invented by opioids in pharma,” Elhadad recounted. “This is not a clinically relevant question. It became relevant because of lobbying for more opioids. It’s not the right way to ask patients how much pain they are in, where it hurts, what type of pain it is.”

Dr. Nadine Rohloff, who studied medicine at WWU Münster and worked in the endometriosis center of the gynecological clinic at the University Hospital Münster until 2018, offered a doctor’s viewpoint on misunderstandings of endometriosis among professionals. According to Rohloff, while biases among doctors are certainly part of the problem, the core issue lies in a historical lack of research that has shrouded the disease in uncertainty.

“A lot of the research that we have is only 10 years old, or even younger, so a lot of the older doctors didn’t really have a lot of knowledge in their studies and in their early years, so there is also a lot of uncertainty for them,” Rohloff claimed. “Speaking from a doctor’s perspective, even if you’re right in the center, there are things about endometriosis that you might not know.”

Rohloff underscored the necessity of integrating endometriosis into medical school curricula for all students, regardless of their area of specialization.

“Endometriosis needs to be in medical school, especially because all the doctors later go in all these different directions, and endometriosis is such a chameleon of a disease,” Rohloff said. “I mean, an orthopedic surgeon might not have many patients with endometriosis, but it’s really good if they have heard of it, because sometimes endometriosis comes with pain in the legs, right?”

Rohloff also argued that establishing specialized programs in endometriosis for aspiring gynecologists, modeled on the specialties offered in oncology and other fields, would be fundamental to eradicating doctors’ misconceptions of endometriosis.

Beyond expanding research and education, the keys to change in the medical community lie in validating the reality of patients’ experiences and recognizing the complex impact of endometriosis on all facets of patients’ lives. This validation requires addressing the disease’s physical and personal dimensions.

“I think it’s important when speaking to patients to really acknowledge and to say that it’s not a psychological disease, it’s not imagined, it’s a problem that you have, we see that,” Rohloff said. “But the thing with chronic pain is that it impacts your life, right? It’s psychological distress. So that’s what we need to think about as well, because the goal of endometriosis therapy, since we don’t have the cure yet, is improving life quality.”

***

At its core, endometriosis-related change is a political issue. To address glaring disparities in research and funding, radical reform must take place at the policy level.

“In my opinion, this disease is the most politically controlled disease by pharmaceutical companies, hospitals and insurance companies,” Cole stated. “When women have been in pain literally for hundreds of years, nothing has been done. And less than $2 is allocated per patient from the American federal government.”

Cole argued that sexist biases lurk beneath this blatant lack of funding and concern. “Because women have always been depicted as being crazy, or hysterical or dramatic, our pain has never been taken seriously, you know, we have always been considered like a second or third class citizen,” she said.

According to Cole, the primary avenues for reform in the American context include increasing funding for research and getting specific insurance coverage for endometriosis—as of now, endometriosis does not have its own insurance billing code because it is not properly recognized by the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Cole sees hope for imminent change in the Biden administration’s establishment of a national Women’s Health Initiative, which was announced in November 2023 and represents the first-ever research initiative specifically devoted to female health in US history.

“We have never once had any initiative for women’s healthcare, ever. And to me, it’s just drastically inhumane that more than half the population hasn’t had any funding or research until 2023,” Cole said.

Cole’s own activism is based in the state of Connecticut. Besides running a support group for endometriosis patients, Cole is currently working with local politicians and members of the Department of Health to “just get the word endometriosis, like a very basic outline of what it is, into our health curriculum here in Fairfield.” She will also be working with state politicians later this year to integrate the term into school curricula across the state, and is involved with a national group striving to establish an insurance billing code for endometriosis.

Looking beyond the American context, Denner said that she hopes “every country in Europe and around the world eventually develops a national endometriosis strategy.” She also hopes to see the emergence of “centers of expertise and access to excision surgery, and funding for non-hormonal treatments.” Denner will keep working with End Endo Silence in Germany and continue her endometriosis advocacy on an international scale.

For Moors, the principal hope for change lies in reshaping societal attitudes to endometriosis. “Politically, I think one of the very first steps is to form alliances that get people and endometriosis patients together, to strengthen our bonds, to strengthen our voice,” Moors said. “Specifically in Europe, I’m really hoping to see more national endometriosis strategies being implemented, since we saw that France had great success with it.”

Elhadad underscored the power of research as a key pathway to justice.

“Politically, I think my true hope as a researcher is that endometriosis is recognised as a worthy topic of research, the same way other diseases that are as or less prevalent are,” she said.

Elhadad claimed that her deepest hope lies in the prospect of a world that recognizes and validates patients’ experiences with true concern and compassion.

“My hope is that anybody who has this diagnosis, or who thinks that they might have this diagnosis, would not feel this internal debate of whether they can even disclose it to anyone, to their job, to their doctors, to their partners, to their family,” Elhadad said.

Alleviating these challenges must not be the patient’s burden, however. Rather, it is an aspiration that requires collective political action. Now more than ever, bolstering the bonds of solidarity among endometriosis patients and allies is vital to confronting what continues to be, in Elhadad’s words, “a true struggle to be heard.”