We’ve all heard the stories of how the world’s largest tech companies had their start, from the likes of Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak creating the first Apple computers in Jobs’ garage to Mark Zuckerberg “discovering” the idea for Facebook in his Harvard dorm. The startup culture surrounding the many companies that we know today—along with the many that have failed—has encouraged enterprising programmers to take enormous risks to create the next big household brand.

This startup culture has become so widespread that it has even seeped into the popular culture representation of technology. When most of us think of programmers, we don’t normally imagine a suit-clad office worker typing away in front of a laptop at their cubicle. Instead, many of us picture a young adult coding in a pair of sweatpants and a hoodie, likely sitting in front of an unnecessarily large monitor at home. It’s clear that startups have abandoned many of the everlasting symbols of professionalism: formal office spaces, formal clothing, and formal etiquette.

The anti-establishment beliefs of these companies can be traced back to the beginning of Silicon Valley itself. Back in the ‘60s, the era of insubordination was in full swing. People took to the streets to advocate for Civil Rights, stop US involvement in Vietnam, and resist authoritarianism abroad. This era lent its hand to a time of immediate and drastic change. Long gone were the principles of gradualism instilled into the minds of American families pre-World War II. The young adults of the time were determined to change the generational beliefs held by their parents.

All it took was a few of those tech-savvy teenagers to transform a period of revolution into a new era of innovation.

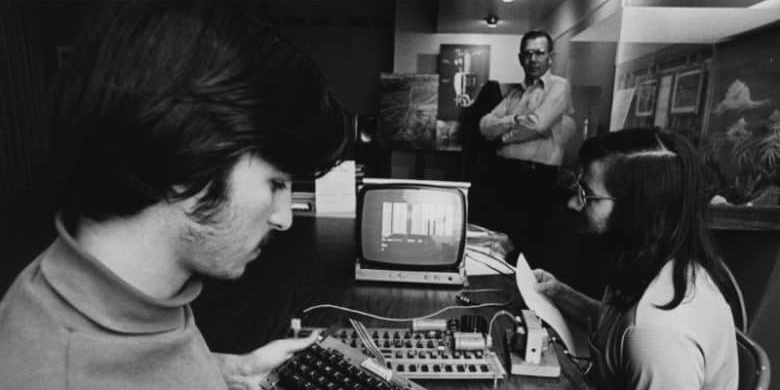

The Homebrew Computer Club, a newly-formed computer hobbyist group, met for the first time in Menlo Park, CA in 1975. With new, young members including Jobs and Wozniak, the club became a centerpiece around which Silicon Valley was built. The club met to discuss ways to make computing more accessible and brainstorm inventive ideas. They then released a widely subscribed newsletter that was a driving force behind the anti-establishment culture we know today. The connections made through this hobbyist group and others provided a platform for computer enthusiasts to voice their thoughts on the future of technology.

With the help of overwhelmingly lax regulations in the industry and a large inflow of venture capital, many members of the Homebrew Computer Club and similar clubs went on to launch some of the foundational companies of modern Silicon Valley. Their organizations, including Apple and Hewlett-Packard, have built an empire matched by no others thus far.

With a word such as ‘innovation’ often being thrown around to justify the lenient regulations put on the tech industry, we are now beginning to see some of the faults of letting a nonconformist sector operate somewhat autonomously.

Companies have begun to sell user data without any liberties for its owners (that’s us, by the way). Smartphone brands have morphed into weapons manufacturers. And as you may have already heard, AI firms have turned your Instagram profile into a facial recognition tool.

The vibrant, innovative startups we once knew have turned into international behemoths, influencing public policy with little regard for their humble roots. As David Polgar, tech ethicist and founder of All Tech is Human, said in an interview with The Politic, “we’ve seen the evolution from [startups] solving a problem to the interconnectedness of how any type of product and design can have a ripple effect with negative externalities.”

A glance at the power of tech’s “frightful five”—Google, Amazon, Microsoft, Apple, and Facebook—shows just how invasive unregulated tech can be. If you need further convincing, just take a look at the attempts people have made to block them from their lives (spoiler alert, it’s pretty much impossible).

But how do we regulate the tech industry without stifling the innovation of small startups?

To answer this question, we must understand the premise behind the counterculture itself. In the eyes of many entrepreneurs, regulation is the enemy of innovation. Putting restrictions on the discovery and use of technology is seen as a foolproof way to reduce creativity in a highly competitive field. After all, the US wants to discover the latest and greatest technology that could automate driving, analyze the human genome, or strengthen military infrastructure more than anyone.

The most important step in finding the balance between regulation and innovation is to first understand that regulation is not a barrier to innovation. While regulation may slow the process of the creation of new technologies, it also reduces the chances that these technologies could be used for nefarious purposes in the future. Oversight is necessary for companies to have the moral compass to fix any of the biases present within their tools. If no one is held accountable, there is no incentive for anyone to fix their tools for the consumer.

It’s also crucial that policymakers act proactively in the regulation of emerging technologies. We see far too often that legislators put restrictions on technology after it has done its damage, rendering its protections nearly useless. This is especially true in the case of facial recognition, in which America is yet to issue a ban on its use in law enforcement despite its well-known flaws.

While we’ve seen the benefits of being proactive through governmental regulation of deepfakes, there is still a lot to be done to protect us from the overwhelming influence of big tech while fostering creativity through startups.

The need for companies to innovate responsively, as well as consider their impacts on the industry’s many stakeholders, is becoming increasingly clear. The informal counterculture that defined many of these companies’ beginnings will no longer suffice to ensure that tech is used responsibly by its consumers and creators.