“It is time”… but for what?

On May 2, Bishop Arthur Hodges of California’s South Bay United Pentecostal Church filed a complaint against Gavin Newsom’s June Executive Order. Frankly inaugurated by this three-word declaration, only an epigraph asking, “Why can someone safely walk down a grocery store aisle but not a pew?” prefaced the statement.

While California has gradually eased statewide shelter-in-place mandates throughout June and May, Newsom’s order restricted the occupancy in houses of worship to “25 percent of building capacity or a maximum of 100 attendees, whichever is lower.” The order did not similarly restrict essential businesses. Because of this incongruence, the Bishop and his church claimed that the state, “intentionally denigrated California churches…by relegating them to third-class citizenship.” Their message continues, “This new regime, where manufacturing, schools, offices, and childcare facilities can reopen—but places of worship cannot—is mind-boggling. The churches and pastors of California are no less ‘essential’ than its retail, schools, and offices to the health and well-being of its residents.”

The California church’s journey to Supreme Court prominence came to a halt on May 29. Despite South Bay’s catalog of indictments, the governor’s order appeared “consistent with the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment.” Chief Justice Roberts joined the Court’s liberal minority to ratify the constitutionality of Newsom’s directive.

While the vast majority of state governments have similarly eased stay-at-home orders, the stock of social distancing mandates upheld in this resolution affirms that the nation’s pivot will not resume utopian pre-pandemic normalcy. In this moment of transition, the Court’s verdict provides an edifying look into religious practice as a modified pillar of life in quarantine; where individuals would naturally turn to religious communities for support, staying apart is the collective prerogative. As such, they have had to adapt.

According to a recent Gallup poll, 19 percent of Americans said their faith or spirituality had gotten better as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. In tandem, as churches, synagogues, and mosques have closed nationwide, a Pew Research Center poll found that the majority of Americans (57 percent) virtually shifted their routine attendance.

As much as barriers to entry have statistically quelled religious participation, our global predicament has fostered a kind of spiritual renaissance—an aura of community-oriented mindfulness that we would not observe otherwise. Images and accounts of religious observance through online Zoom live streams, pre-recorded YouTube sermons, and in some cases, drive-in theaters have underscored the empirical significance of American religiosity as an Armageddon revitalization.

“The numbers were staggering,” wrote Yale University Chaplain Sharon Kugler. Reflecting on her office’s engagements since Yale moved the semester online, she continued, “People were longing to see each other in some way throughout the semester.” The Chaplain’s Office made all services and programs virtual on March 13.

According to Chaplain Kugler, mandated separation in this time of hardship has been the most frustrating part of these past months, “We have met with people who have lost loved ones to the virus, people in difficult home situations, people who are struggling with their mental health or suffering from some sort of abuse…. It has been overwhelming and frustrating because our instinct [is] to physically reach out [or] offer a gentle touch or a hug, and we cannot do any of that. We have to trust that even imperfect efforts help in some small way.”

Various student groups have rallied to deliver an energetic slew of quarantine programming in company with the Chaplain’s Office. Given this year’s timing of the Muslim holy month Ramadan, Yale’s Muslim Student Association (MSA) was especially implicated in this light. As of May 30, not only had the MSA hosted numerous interfaith dialogues and events, they had also organized a virtual senior send-off, and various Ramadan-oriented social media campaigns as well.

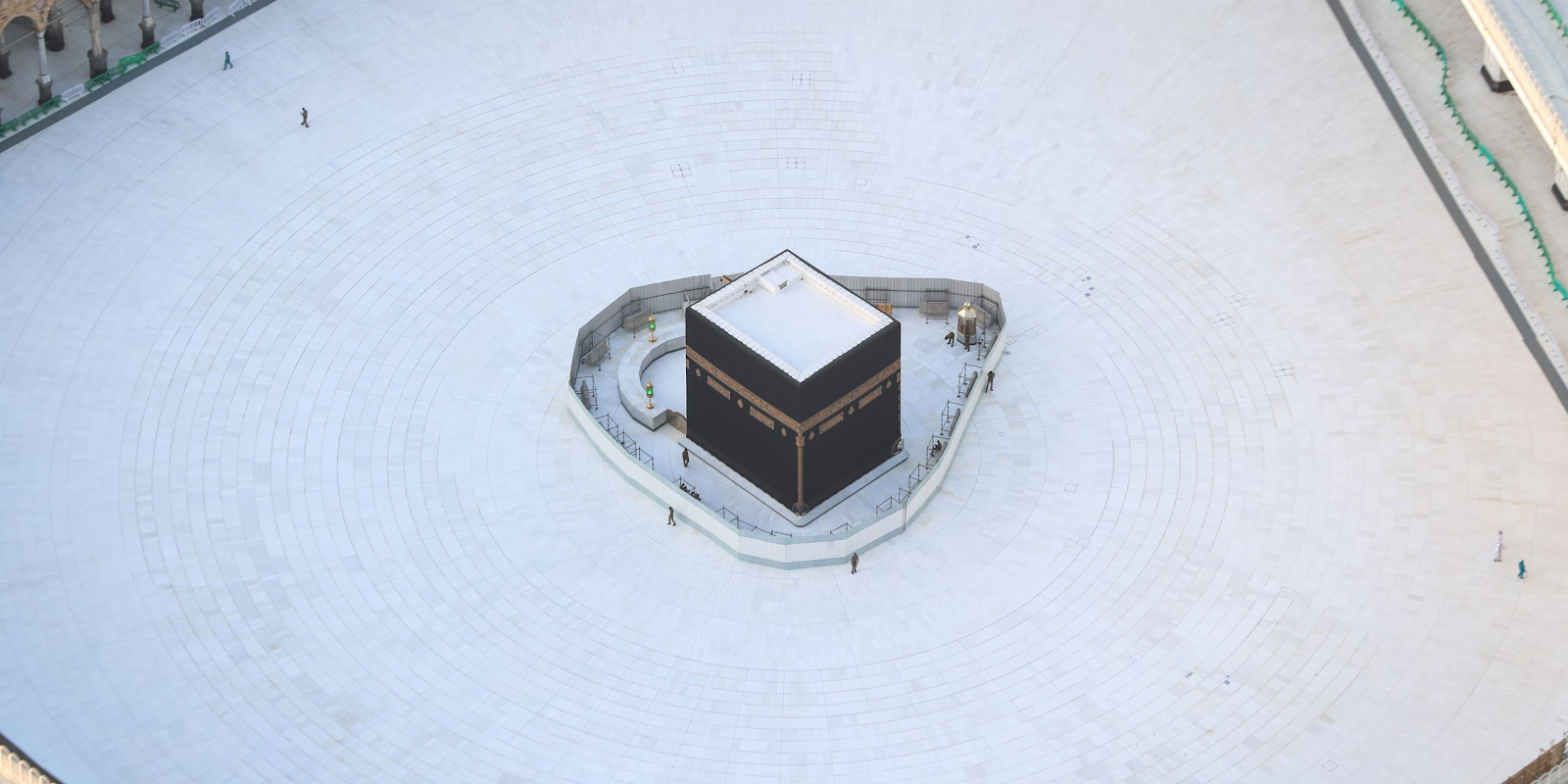

While Ramadan is widely celebrated as a time of prayer, reflection, and most importantly, community (exactly what these events tried to replicate), quarantine has brought a newfound significance to the holy month. “I did miss out on [the community aspect of Ramadan],” said MSA President Yousra Omer ‘22, “We go to the mosque every single night,…we have community Iftars…. Before Ramadan, my dad would go to the mosque and pray twice a day, and they were like, ‘please, stop doing that—please don’t come to the masjid…. Stay home.’”

Despite this ostensible loss, however, the kind of self-reflective meditation necessitated by this year’s Ramadan was undeniably bound to quarantine. Because everyone was home, Omer’s family simply “experienced each other for a while.” This environment helped her “realize” and “develop” in ways that she self-admittedly would not have pre-corona. Further contemplating quarantine’s more therapeutic facets, she continued, “I think [COVID-19] has definitely pushed people to really understand their own religion;…it’s definitely something that I want to continue…. Just a point of reference about where we can be and what we can do when all the distractions are taken away.”

The COVID-19 pandemic similarly strengthened Rebecca Reid’s ‘23 relationship to faith. As a self-described “preacher’s kid,” the community pillar of religious practice defines Rebecca’s experience with Christianity, “I was literally born into the church. My earliest memories of religion were sitting in a pew on my dad’s lap listening to the choir sing as my mom prepares to preach.”

As Reid’s transitioned to college—asking her friends questions she was too shy to ask her parents (both Biblical scholars)—her on-campus spiritual community helped her discover faith beyond familial obligation, “One of the challenges that comes with being a preacher’s kid is grasping onto your faith for yourself…. I’ve been able to find a community on my own [in college] and determine what religion means to me.”

She has maintained these connections in quarantine, “It’s been very cool to be able to text other Christians that I know and ask them about deep spiritual questions, even in quarantine…because of technology and being connected with everyone, we’re still able to talk to each other and be engaged in the same way.”

Virtual spirituality similarly bonds Reid’s community at home. “We put up a “screen”— which was just a white blanket—and put the projector in front of it so that it was on the wall behind my mom;…we used my music stand as her podium…. We were trying to replicate a formal experience as much as we could,” Reid said.

With this patchwork mix, Reid’s family made her mother’s services available through Facebook Live and Zoom conference calls. To keep this time interactive, they solicited prayers from members of their church to include throughout the call. They found that this transition allowed people to “tune in” in ways that they hadn’t before, “Since we’ve gone online, it’s opened the opportunity for a lot more people to be engaged in the church.”

Cami Árboles’s ‘20 acknowledges a similar experience when discussing how the pandemic prompts an intimate examination of self. The world turning on its head has strengthened a sense of awareness that Cami credits to her Catholic upbringing, “I’ve tried to be so much more mindful of how I express gratitude and when I express gratitude [in this time]…I’m so grateful that I can say that I am in good health, my family is in good health, we have shelter, we have food, I just got my degree from Yale! Everything’s pretty good, and so, I’ve definitely strengthened my relationship with expressing gratitude.”

As a creative, this time of isolation has allowed Árboles to access her creativity in “ways that aren’t limiting…. I’ve been untapping my creativity in ways that are just so liberating. I think the power of self-expression is really great,…there’s a lot that you need to release and creativity is a great way to do that.”

This need for a creative release also takes the form of pole dancing for her. After convincing her aunt to install a pole in her living room (just a few miles from Árboles’ home in South Pasadena), Árboles routinely devotes several hours each day to her practice, “in a way, physical activity and the creative nature of pole dancing has always been very important—it’s kind of a ritual…that’s my sacred time.”

Though Árboles’ increased sense of quarantine spirituality is not concretely bound to religion, our home-bound existence defines it nevertheless. Beyond that, Árboles’ spiritual practices in quarantine are a direct reflection of a religious evolution grounded in her pre-college life, “I’m probably the farthest away from a practicing Catholic that I’ve ever been in my life. That being said, I find myself a far more spiritual person than I was when I was in high school, which is kind of funny because I learned the value of commitment and community when I was in those [Catholic] circles.”

Árboles, Omer, and Reid perfectly exemplify what the past months have meant for so many of us. Though we have struggled, we have found our sea legs in unchartered waters; innovating for what seems like survival.

To quote Chaplain Kugler, this pandemic has “laid bare all the fissures in our social fabric.” As one meteoric trauma follows another, our continued capacity for pioneering keeps our heads above water—it keeps us breathing; it keeps us from suffocating under the weight of our crumbling reality. As we look to the future, this chameleon-like versatility will sustain our progress.

***

All interviews concluded with a simple question: “What have you prayed for recently?” This piece wouldn’t be complete without sharing this light in our present darkness.

Sharon Kugler

“We pray for the families and loved ones of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and countless others who have to live with a horrible loss that began with one final breath. The past several weeks we have heard and seen the word ‘essential’ often and we have been thankful for those whose work has been deemed so to keep us going during a global pandemic. But now, in this moment of national grief and personal trauma, we call upon You to help us with something else that is essential’ for the other pandemic that has been going on in our country for over 400 years. We ask You to bless us with ‘essential knowledge’…. Bless us with the ‘essential knowledge’ that the trauma to Black bodies, indigenous bodies, all people of color, and others who are marginalized is trauma that is physical, spiritual, and emotional, it is a trauma that persists through generations, and it matters.”

Rebecca Reid

“I recently prayed for a lot of things. Last night I prayed for all the protesters and demonstrators—for their safety. [I also prayed for] this country to get the message…. You just need to listen to why we’re doing this…. I prayed that no one would ever feel as scared as the victims of police brutality…. nobody should ever feel that scared.”

Cami Árboles

“[I’ve prayed for] all of my Black brothers and sisters right now obviously… I went to high school with a lot of privileged white women who’d react like Amy Cooper did…. I’m thinking of those people, and I’m praying for them to educate themselves…. All our essential workers, I’m praying for them—there’s a lot to be praying for right now, and the thing is, I don’t even really pray, but in a way, I think that thinking about things and talking about things and spreading awareness is a form of prayer.”

Yousra Omer

“I am hopeful for something better in the future. I think things come in waves, so there will be a wave of bad things and a wave of better things—hopefully, the next wave of bad things doesn’t take us out as long as this one.”