Adrienne Gear’s early days as a teacher brought an unforeseen challenge: despite her dedication, she was failing in her most critical responsibility—teaching her young students to read. “I love children’s books and I brought them into the classroom. Some kids were able to read them,” she explained, “but lots of kids couldn’t because we weren’t teaching them what we should.’”

The teaching method Gear had learned during her education degree– “Whole Language,” a philosophy that emphasizes immersing children in books to encourage the natural development of reading skills—was failing to provide students with the direct instruction they needed. “The idea at the time,” Gear recalled, “was that we’re going to surround our kids with great books, and we’re just going to cross our fingers that they figure it out.”

A turning point came for Gear when a new movement took off in American classrooms. Coined as “Balanced Literacy,” this framework hoped to maintain Whole Language’s emphasis on comprehension, writing, and cultivating genuine engagement with books while adding direct and individualized instruction. “Early in my career, I had literally spent probably the first five or six years in the classroom, surrounding kids with books, but not knowing how to teach them. [Balanced Literacy] was groundbreaking for me,” explained Gear.

Guided by the principles of Balanced Literacy, Gear introduced smaller reading groups, regular assessments, and designated levels based on each child’s skills. The individualized part of instruction was most meaningful, “One thing that every teacher knows is that you are never going to have a class of children who are reading at the same level,” Gear explained.

But the movement that Gear credits as revitalizing her teaching career is now widely seen as one of the education system’s biggest missteps. Once embraced for its emphasis on cultivating a love of reading through exposure to rich texts, Balanced Literacy is now on the losing end of a centuries-long battle across American classrooms, commonly referred to as “The Reading Wars.” Standing in opposition is phonics—the now-dominant approach—that teaches children to decode words by sounding out letters and syllables.

The Reading Wars have taken on many forms since they began in the 19th century, though most would agree that the debate is larger than just teaching methods. While phonics-based instruction has long existed as a method for teaching reading, it was often treated as one option among many—its adoption coming down to instructor preferences and district mandates. At the core of the pendulum swings between Whole Language and phonics is a power struggle concerning who gets to decide what children are taught in schools. The struggle plays out across research settings, state legislatures and classrooms.

Most of the criticism about Balanced Literacy revolves around one distinct aspect of the method: cueing. Cueing is a strategy often used to help beginning readers figure out unfamiliar words by guessing based on context, pictures, or sentence structure rather than through decoding the sounds of the word.

Gear offered a typical example of how it is used. In a book about farm animals, children might first see a picture of a horse alongside the sentence, “A horse is on the farm,” followed by a page showing a pig with the matching sentence, “A pig is on the farm.” The pattern and images guide students to rely on context rather than fully breaking down the words.

Gear explained, “If a child is reading that book, once they know the pattern, they can get through the book and it sounds like they’re reading. But the problem is, if they saw the word horse in a different book with no picture, they would not be able to read it.” This flaw in the balanced literacy system allowed many children to slip through the cracks. While they appeared to be reading, they actually lacked a solid-foundation necessary for reading proficiency.

As concerns about the shortcomings of cueing began to surface among educators, parents, and policymakers, so too did a growing body of research—offering phonics as a more structured, scientific alternative. This collection of research is colloquially referred to as the “Science of Reading.” It implicitly casts doubt on methods outside of phonics’ bounds.

Recently, the APM podcast “Sold a Story,” which details how once popular reading curriculums conflicted with decades of research, has spurred a fresh wave of legislation and endorsement for phonics-based instruction. The podcast’s release, alongside growing grassroots movements advocating for children with dyslexia and concerns about post-pandemic declines in literacy have led 25 states to pass laws mandating “evidence-based” reading instruction.

Minnesota state senator, Zach Duckworth, was behind two such bills in his home state, which mandate phonics instruction and provide additional funding for such measures. His motivation was personal, “Before I was in the State Senate, I was a school board member. I’ve also got four little kids, and I’m somebody personally that, when I was in elementary school, got a little bit of extra help with reading.”

Duckworth, like many students, didn’t take naturally to reading, but credits his development to methodical phonics lessons. When Minnesota, like many other states, saw literacy rates decline in recent years, Duckworth took a closer look at reading instruction and was surprised by how far schools had moved away from that approach. “When I was a kid, I used to hear commercials for Hooked on Phonics. I can’t remember the last time I’ve seen or heard a commercial for them,” he explained.” Hooked on Phonics, a commercial reading program focused on letter recognition and audio-visuals, gained widespread popularity in the 1990s through its extensive advertising in television and radio.

Though it is too early to see the full effects of his legislation, Duckworth is optimistic. “When they receive the instruction,” he said, referring to new teacher training initiatives, “generally the feedback is pretty good. And many of them say they wish they would have received it much sooner—even when they were getting their teaching degree.”

In the long run, Duckworth has little doubt about the improvement that phonics-based instruction will bring. “It’s not like you have two different methodologies or forms of instruction that essentially get the same result, and you’re just picking one over the other,” he explained, “Not even close. Science of Reading blows Whole Language out of the water, by far.”

However, some experts remain skeptical of the promise that phonics-instruction will solve literacy problems in American schools, especially when it comes to proficiency among older students. “Nobody has a very good understanding or knowledge of how reading is taught in the United States,” explained Timothy Shanahan, professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago College of Education, “We don’t have any kind of ongoing monitoring of instructional practices in schools.”

Most of the tracking used to inform the movement is actually based on national reading scores, where observers see correlations between an increase in phonics-based reading programs and subsequent improvements in fourth-grade test scores. However, Shanahan explained that reporters and policymakers may be focusing too much on these specific measures. “They have the idea that if they get those third grade or fourth grade reading scores up, then the problem is solved,” he explained, “But if you look at the scores over the last 50 years, even when the third grade or fourth grade scores are up, the eighth grade scores stay flat.”

The long-term advantages of phonics are still up for debate, but the data for students with dyslexia and related learning difficulties is clear: they benefit significantly more from phonics instruction. This group of students has become a focal point for educators and policymakers addressing the gaps left by Balanced Literacy.

Caryl Frankenberger, director of Frankenberger Associates Learning Solutions Center in Connecticut, works closely with these students, teaching the fundamental skills overlooked in less explicit methods of instruction.

Many students, she explained, enter school already struggling to blend sounds and grasp the alphabet. “When they go into first grade, if they don’t receive something more structured, they really struggle to learn to read. They may or may not be dyslexic. Not all of them are,” she said. Frankenberger added that with explicit instruction early on, many of these students could avoid reading difficulties later.

“I’ve worked with kids who go all the way through high school and get into college without actually being able to read well,” Frankenberger explained, “And it’s shocking when it happens, but I’ve seen students show up in college—bright kids, good students—but they struggle so badly with reading that it finally gets noticed. It happens more than people think.” Frankenberger referred to this group of students as “instructional casualties,” a phrase borrowed from neuroscientist Reid Lion.

Frankenberger added that the system itself is responsible for these issues, not individual teachers. “You have teachers who mean well but were never given the tools to actually help struggling readers. And then they’re thrown into a classroom with 30 kids and expected to somehow individualize instruction for the five or six students who are falling behind.”

Gear shares this concern, questioning whether a shift toward phonics can fully solve the challenge of reaching all students, particularly for those who grasp phonics early and require deeper, more challenging instruction to stay engaged. “Just how the balanced reading worked really well for 80% of the kids, but 20% weren’t getting it, I feel like now we’re replicating that. Phonics is being taught, and 80% of the kids are really responding to the orthographic mapping lessons, but 20% are bored out of their mind.”

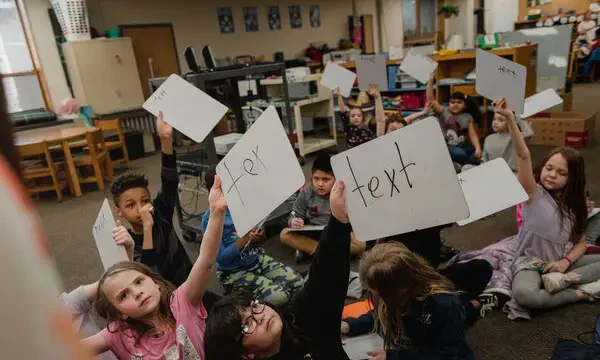

On a recent visit to a classroom, Gear’s concerns came to light as she observed a younger teacher instructing through the phonics method. “She was doing an amazing phonics lesson that I just happened to be in the room watching,” Gear explained, “But what she didn’t notice, that I noticed right away, is three little boys at the back of the carpet, and they’re rolling around on the carpet…and they’re looking at each other and they’re groaning because they know the short letter A or whatever sounds that she was teaching.”

This disengagement from certain students reflected Gear’s concern that such rudimentary phonics instruction is excluding certain students. It also points to a deeper concern of Gear’s that the richer, meaningful side of reading is being lost to a more mechanistic approach. “What I worry about right now in the reading instruction that I’m seeing is so much time in a classroom is spent on the code that the comprehension is now on the back burner,” Gear explained.

Like Shanhan, Gear agreed that comprehension should receive more focus in the larger conversation about how reading is taught. “I know that instruction in phonics is essential to a reading program, and I am never, ever arguing that what you’re doing in those programs are not important.” she explained, “But so is comprehension…because if we forget about it, we’re going to have a generation of master decoders who don’t understand what they’re reading about.”

Gear’s concerns highlight a lingering issue in the Reading Wars that is yet to be resolved—while phonics has emerged as the dominant method for teaching young students, perhaps Balanced Literacy should not be dismissed entirely. The data may have clarified how students learn to recognize words, but the deeper question of how to impart meaning from those words remains uncertain.