1980s, South Korea –– Bak Jong-cheol, a student leader at Seoul National University, was one of many young activists struggling against the South Korean military dictatorship. Later, when Bak was interrogated for his involvement with pro-democracy movements, he refused to confess and give up his fellow activists and was fatally tortured in detainment. Bak Jong-cheol’s death on January 14, 1987 at twenty-one years old inflamed a nation simmering under autocratic oppression, culminating in the June Democracy Movement of 1987. The Democracy Movement saw nationwide mass protests that forced the government to hold elections and undergo democratic reform, leading to the establishment of the Sixth Republic—the present-day government of South Korea.

In 2022, a Disney Plus show switched on in sheltered living rooms. The show was Korean TV drama series “Snowdrop,” which took its international audience back to South Korea amid the Democracy movement. But the story quickly shifted from 1987 as Bak Jong-cheol and his activist peers knew it—episodes depicted university student Young Ro giving shelter to a North Korean spy, Suho, whom she mistakenly believes to be a pro-democracy protester chased by state secret service agents. From there, Snowdrop unfurled into the unlikely pair’s love story. A clever, arresting plot for viewers new to the backdrop, but hauntingly familiar for those closer linked to the events of 1987: the government had used the very pretense that dissidents were linked to North Korea, prosecuting students on charges of being North Korean spies.

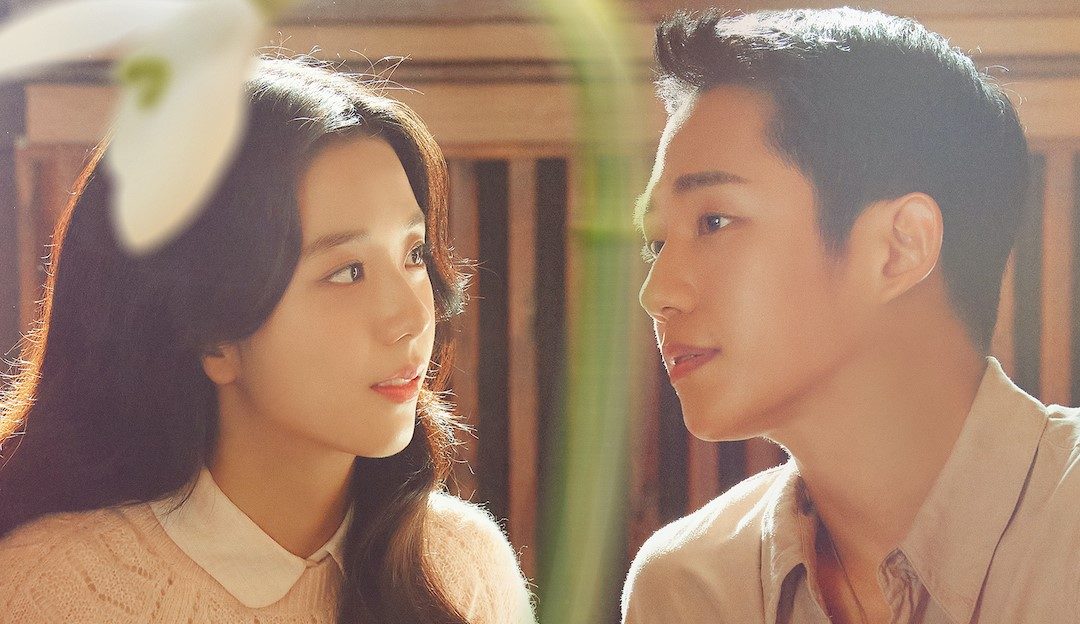

Projected to be a huge hit in Korea and ambitious for international audiences, Snowdrop stars Korean girl band BLACKPINK’s member Jisoo and actor Jung Hae-in in lead roles. But the star-studded cast was not immune to backlash for historical revisionism—Snowdrop first garnered controversy in Korea in 2021, prompting calls for the show’s cancellation and withdrawals of corporate sponsorship. On December 19, a petition was posted on an online bulletin of the presidential office demanding the show to be taken off-air: “It is true that there were many activists who were tortured and killed after being falsely charged with being spies…The drama dares to portray the fact and definitely undermines the value of the pro-democracy movement.” More than 300,000 people signed the petition by December 21. Ensuite was a letter by 34 scholars from South Korean and U.S. institutes, including Harvard and Princeton University, asking Disney to review historical references made in the show: “We are not writing to request that you stop streaming the show… Rather, we write to request that your company seek experts—there are many, well-qualified modern Korean history experts in Korea and all over the world—to carefully examine the historical references made in the show, and consider for yourselves the way those historical references are used.” Further denouncement came from supporters of Park Jong-Cheol who saw the show’s plot as excusing the violent oppression of the democratic activists, reinforcing the regime’s “claims that victims are just coincidental to its crackdown on North Korean spies.” Rounds of public outcry prompted withdrawal of sponsorship and advertising deals from the show, including producer P&J Group and fashion brand Ganisong.

In response, director Jo Hyun-tak and broadcaster JTBC tried to justify the show’s plot on the grounds of creative integrity—emphasizing that everything in the show, except for its time setting, is fictional. “The drama is set in the year 1987, but, except for situations like the country being under the reign of a military regime and electing a president at that time, all other things, like its characters and institutions, are fictitious,” Jo Hyun-tak said in an online press conference. JTBC stressed that Snowdrop is not intended to defend the military government’s claims that Pyongyang was behind the pro-democratic movement in the 1980s, highlighting that there is no North Korean agent participating in the protest throughout the series.

Still, the show continued to make its way to the global screen on Disney Plus. The impact of cultural products, the likes of film and media, are not to be slighted as mere, transient entertainment: Culture is both elusive and pervasive in shaping public opinion as a compelling device of soft power. In turn, platforms must grapple with the responsibility of relaying the right messages—what is the goldilocks trade-off between creative entertainment and historical integrity, free expression and content moderation? Should a more prudent approach be taken in adapting sensitive historical episodes for entertainment purposes? Beyond the responsibility of individual producers on the historical integrity of their projects lies the bigger picture of international flows of culture imports and exports. Cultural products have long been the West’s to export, with US giants like Hollywood at the helm. Positively, this stream of cultural products brought creative works and boundless entertainment to a global audience. However, the nature of media and film as cropped and filtered versions of ‘real life out there’ can misrepresent and draw skewed impressions.

Presently, America faces an import surge of foreign media, a “cultural tiding” that is refreshing Western perspectives on pop culture’s capacity to influence intercultural comprehension. With imports of historical fiction like Snowdrop, the risk of misinformation on Korean history is imposed on Western audiences. This turn of cultural flows sheds new light on the responsibility of international platforms, zooming out of independent producers, to manage misinformation. The debate of platform censorship was most recently pushed to center stage with Elon Musk buying up Twitter and pledging to allow untethered free speech on the platform. Musk’s vision is criticized for its potential to unleash hate speech, misinformation, and incendiary statements. These are risks that would spill beyond American borders as Snowdrop’s historical distortion did beyond South Korea—countries prone to the stoking of hate or violence between groups are particularly susceptible to exploitation and radicalization of free speech in cyberspace. This is yet another thorny demand for meticulous balance: on the one hand, free reign to producers makes platforms vulnerable to misinformation; on the other hand, censorship conjures extreme cases as China’s Great Fire Wall (blocking websites including a range of foreign media that misalign from state narrative) and North Korea’s draconian speech suppression. Snowdrop’s adaptation of an incendiary historical episode has split its audience between culpable historical distortion for some and harmless story-telling for others. Extrapolating from one show, we are faced with the wider, emerging climate of intercultural communicative responsibilities—a roulette to respect perspectives and fact-check while magnetizing the foreign and unknown.