One freak occurrence across the globe froze our lives in place. A microscopic fleck of protein prevented us all from seeing our families and friends, from attending parties and movies, from even showing our faces in public. How can we continue to live, knowing that existence itself is so fragile, so chaotic, so absurd?

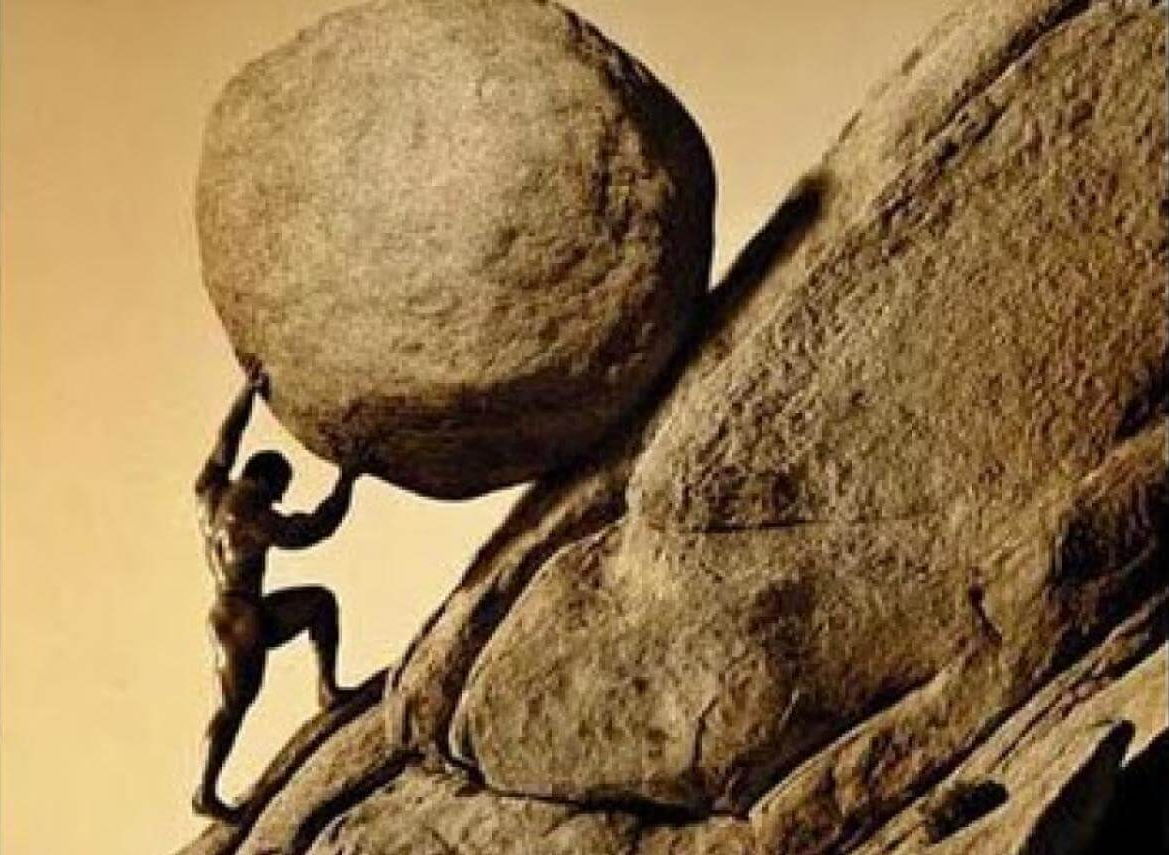

For French existentialist Albert Camus, the questions surrounding the meaning of existence lay beyond the scope of human reason. Yet, despite our inability to understand our condition, Camus believed we all continually attempt to find meaning, purpose, and reason. This paradox, rational beings forced to grapple with an irrational world, characterizes our absurd existence. Camus painted his portrait of human existence most famously in his essay The Myth of Sisyphus in which he likens the human condition to the torment of the mythical King Sisyphus. As punishment for cheating death, King Sisyphus must push a boulder up a hill ad infinitum. Every time Sisyphus approaches the summit, the rock slips back down, and Sisyphus must begin again. In torment, we endlessly pursue ultimate truth and meaning, only for definite answers to slip between our fingers, forcing us to start building our understanding anew.

I certainly experienced the Sisyphian struggle during the lockdown. Just a few weeks in, I decided that lockdown would be good for me. Adopting the mantra “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger,” I embraced the experience, believing I would use my COVID experience to handle any of life’s subsequent absurdities. But if I needed to be tempered in COVID’s crucible, then surely there must be a reason? Was something worse headed our way? Even if preparation for some greater evil was the “point” of COVID, what was the point of that subsequent struggle? Much like Sisyphus, any attempt to rationalize the pandemic fell apart just before I could find a definitive answer.

Jean-Paul Sartre, a fellow French existentialist, painted a similar landscape of human existence. In his public lecture “Existentialism is a Humanism,” delivered in 1945, Sartre argued that human existence comes before essence. “Existence” in this sense refers to the atoms of the thing itself: the tangible reality we can grasp. “Essence” connotes everything else: the qualities or form that make a thing what it is. Consider a pen. The existence of the pen would be the physical manifestation of an ink cartridge surrounded by a plastic body. The essence of a pen is the concept of an ink-based writing instrument. For a pen, the essence precedes existence as a craftsman must first hold the idea of a pen – what functions it ought to perform and how it will perform them – before he can bring the pen into existence. However, for humans, existence precedes essence. Life has no intelligible meaning, thus we are born (read exist) before we have been assigned function or purpose.

Again, Sartre’s ideas ring true in the year of COVID. Lockdown destroyed our quotidian routines. What was the purpose of going to the mall anyway? Were mundane activities – going to the mall, attending school, eating with friends – integral to our essence? If I did have some definite essence that I should obtain through my existence, then was COVID separating me from the very point of my being? Then how can I live, knowing that I have been severed from my reason for existence?

Many people stop their foray into existentialism there. Thinkers like Camus and Sartre portray haunting depictions of existence. I contend they provide some of the most heartening answers. Unlike philosophers who paint rosy pictures of life, existentialists are capable of providing meaningful answers because they ask meaningful questions. Take Camus’s Sisyphus. Sure, there appears to be no meaning to his repetitive life, but Camus argues his actions are meaningful in and of themselves. To Camus, “we must imagine Sisyphus happy” as the struggle itself is enough to fill our lives with joy. The action of struggle has meaning and merit.

Sartre also finds that action is the solution. Since our existence precedes our essence, we have the power to author our own meaning. In saying “we are our actions,” Sartre argues our actions define us, but also that we define our actions. To Sartre, humanity is “condemned” to freedom because we carry the burden of defining ourselves.

COVID has presented a unique opportunity to test out these existential dogmas in our own lives. We rebelled against the absurdity of our circumstances, searching our lives for the meaning of the pandemic. This rebellion in and of itself had meaning. We found ourselves questioning the purpose of our existence in the absence of family and friends. Yet, we also found the chance to author new meaning in our lives. We had the opportunity to exist in a new context, to define our essence in the solitude of lockdown instead of the maelstrom of the public. In many ways, existentialism replaces the nouns of meaning – family, friends, school – with verbs of meaning – struggle, define, labor. During a time in which those nouns are stripped away from our lives, these verbs are all we have. Let’s take a lesson from the bleak and dreary existentialists.