Every train that travels between Beijing and Ulaanbaatar must come to a halt at the Mongolian-Chinese border. Although China receives around 90% of all Mongolian exports and supplies Mongolia with more than one-third of its total imports, the track gauges between the countries differ by 85 millimeters.

This miniscule difference is enough to ensure that each railroad car must be raised in the air and its wheels, or bogies, changed before it can continue on to its final destination. The process can take up to 36 hours for an entire train.

This reality reflects the tense and impossibly taut relationship between China and Mongolia, stemming from both historical and contemporary causes.

Despite their country’s geographic proximity to China, Mongolians’ relationship with the Chinese is fraught: xenophobia towards Chinese people—termed sinophobia—within Mongolia is far-reaching. Today, this national sinophobia has tangible impacts on not only cultural interactions between Chinese and Mongolian citizens, but also business investment and industry within Mongolia.

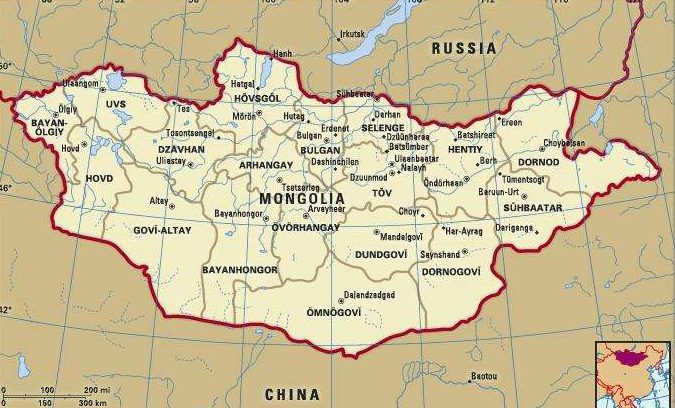

Mongolia’s contemporary relationship with China can be traced back to the year 1691, when Outer Mongolia came under the control of the Manchu Qing Dynasty (Inner Mongolia, currently an autonomous region of China, fell to the Chinese in 1636). This conquest sparked a period of Chinese domination of Mongolia that would span more than 200 years, until 1911.

Morris Rossabi, an Adjunct Professor in the Department of Eastern Asian Languages & Civilizations at Columbia University, said in an interview with The Politic, “the Mongols view that as a period of great oppression and exploitation by the Chinese [which has caused] a heritage of animosity and hostility between the two peoples.”

Tensions between the two countries were replaced by a period of brief amicability in the late 1940s, when Chinese communism spread to Mongolia. Chinese workers came to Mongolia as technical advisors and laborers with the goal of improving Mongolian infrastructure.

However, with the eruption of the Sino-Soviet dispute in 1956, the rift between the Mongolians and Chinese rose again, with the Mongolians siding with the Soviet Union. Until the 1980s, back-and-forth attacks dictated the Mongol-Sino relationship. The existence of varying train gauges between the two countries, or the lack of asphalt roads connecting Ulaanbaatar and Beijing, can be traced directly back to the point at which Mongolia decided to move closer to the Soviet Union and away from China. The railroad gauges in Mongolia are known as “Russian” or “Soviet” railways as this gauge is primarily used in former Soviet states, such as Georgia.

Despite Mongolia’s economic reliance on China today, before the fall of the Soviet Union, trade with China represented a mere 1.5% of Mongolia’s total foreign trade, according to Reuters. During the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s, the Soviet Union prohibited Mongolia from pursuing normal trade relations with the outside world. With the fall of the Soviet Union, whose aid at times represented one-third of Mongolia’s GDP, Mongolia collapsed into a deep recession at the start of the 1990s.

Over the past three decades, Chinese trade has slowly but persistently filled the void in the Mongolian economy that the Soviet Union’s fall left. Today, according to Reuters, trade with China represents 68.5% of Mongolia’s foreign trade.

Jack Weatherford, the former DeWitt Wallace Professor of Anthropology at Macalester College, explained in an email to The Politic that “China determines the prices of goods and how much can come out. For example, they buy Mongolian coal at a one-third discount of the world price for coal. China is overwhelmingly the largest investor in [Mongolia], the largest source of loans, and the only country allowed to operate its bank.”

Despite the degree to which Chinese investment has shaped the country, Mongolia today prefers to align itself with Russia rather than China, following earlier Soviet-era models. Mongolia is dependent upon Russia for 90% of its energy supplies, and in general, Mongolians prefer Russian goods.

Weatherford said, “Russian goods and technology are highly respected—as are Japanese, Turkish, and Korean—while Chinese goods are disparaged; [however… ] most of the goods are Chinese.”

To say that this is the result of only a governmental preference toward Russia would be to ignore the legacy of underlying anti-Chinese sentiment, or sinophobia, that still exists in the country.

In 2016, a top Mongolian rapper, Amarmandakh Sukhbaatar, performed on stage in Ulaanbaatar in a red deel, or traditional robe, embroidered with a swastika. In response to his performance in the outfit, he was attacked onstage by a Russian diplomat with a bottle and spent ten days in a coma.

Although Sukhbaatar defended his attire by emphasizing the history of the swastika as a symbol used in Mongolia long before the Third Reich appropriated it, Sukhbaatar’s use of the swastika may better reflect the rise of neo-Nazi groups in Ulaanbaatar over the past few years.

These groups, one of the best known being Tsagaan Khas, have received significant media attention both inside and outside of Mongolia. The majority of Mongolians are not members of these groups, even though many share some anti-Chinese opinions.

However, by focusing primarily on neo-Nazi groups, the media understates the influence of anti-Chinese sentiments in Mongolia. “[Media coverage implies that] there are only these really extreme groups that do this…[but] xenophobia is really well distributed in Mongolian society in all contexts,” Marissa Smith, a sociocultural anthropologist and the current research coordinator for the McNair Scholars Program, said in an interview with The Politic.

This racism—from the prohibition of Chinese characters on signs in Ulaanbaatar to racial slurs—stems from fears that China will attempt to take over Mongolia again, just as the Chinese have done in places such as Tibet.

Shirchin Baatar, a Mongolian-American currently living in the San Francisco Bay Area, explained that during his high school years in Mongolia during the 1970s, China’s brief engagement in the Sino-Vietnamese War sparked fears in Mongolia. “We suspected that China would attack next time in Mongolia,” Baatar said in an interview with The Politic.

These experiences have led to Mongolians’ adopting a cautious approach towards China and Chinese people. “We don’t hate Chinese people,” Baatar said, “We are just very careful and cautious about Chinese politics and economic politics and religious politics.”

Beginning in 2012, the Mongolian economy, which had previously been expanding at astronomical rates, began to contract severely due to a plunge in the price of raw energy materials, particularly copper and coal which are two of Mongolia’s primary exports. Alicia Campi, an adjunct professor at Johns Hopkins University and a former U.S. State Department Foreign Service Officer, said in an interview with The Politic that until that crash, Mongolia had adopted a stance towards China that was “deliberately” exclusionary.

After the crash, the Mongolian president at the time, Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj, began to seek active relations with China by way of a trilateral partnership between Russia, China, and Mongolia. As a result of this trilateral association, Mongolia is looking to become a type transit and economic corridor between Russia and China, with the three countries becoming better connected through railroad development, highway construction, and a gas pipeline.

Campi continued, “Mongolia’s relations with China…in this trilateral setting…are going back to pre-democratic relations with China where Mongolia’s relations with China are, to a major degree, being influenced by China’s relations with Russia.”

While seeking to be independent of China as a result of historic and contemporary prejudices, Mongolia has made itself even more dependent on Russia. And while some Mongolians respect the need to move towards China as a trade partner for the sake of development and modernization, others would avoiding moving closer to China at any cost.

Campi said that “most Mongolians believe they should temper economic development… in order to be sure that they are not flooded by foreign workers, and particularly Chinese workers, [and] if that means they have a smaller number of investors [or] if that means there is a slower [-growing] GDP, then that is worth it.”

In this country of just over three million, which was estimated to be the fastest-growing economy in the world as recently as 2011 when its growth was 17%—before becoming what The Wall Street Journal called the “Land of Lost Opportunity”—factors driving investment may be more complicated than they first appear. In a society long dictated by its nomadic lifestyle and its unique culture, the prospect of Chinese domination, as it appears has been attempted in Inner Mongolia, is not a worthwhile price to pay for economic prosperity.

“We at least must suspend our judgement,” Campi said, “and look at the issues that we are talking about to see if the strategy, the feelings, the information that is in front of us is the reflection of something deeper.”