“In sixth grade, we were greeted by metal detectors and school police officers. When you walked into the building, that was the first thing you saw.”

That’s how Tamir D. Harper, a rising junior at American University and co-founder and Executive Director of UrbEd Advocates, began detailing his educational experience growing up in Philadelphia. After transferring to schools in the more-affluent southern Philadelphia community for 7th grade and beyond, Harper became aware of just how differently safety protocols were enforced across the city. His school in south Philly did not have metal detectors, and School Resource Officers were nowhere near as involved in this school system as they had been for him as a sixth-grader. Harper discussed that, as it stands, policy makers are “incriminating students by the zip code they live in and the color of their skin.”

In his conversation with The Politic, he continued by saying, “if you [walk] into a building that feels like a prison, that doesn’t have school supplies, that has substitute teachers every day, that is dark, with bars on the window—it affects [you, the student] mentally. Any human being who understands adolescent development will not deny that.”

These experiences, shared by thousands of underserved students in Philadelphia and millions across the country, clearly portray punitive institutions within school settings for what they are—yet another example of educational inequality in America on the basis of race and socioeconomic status.

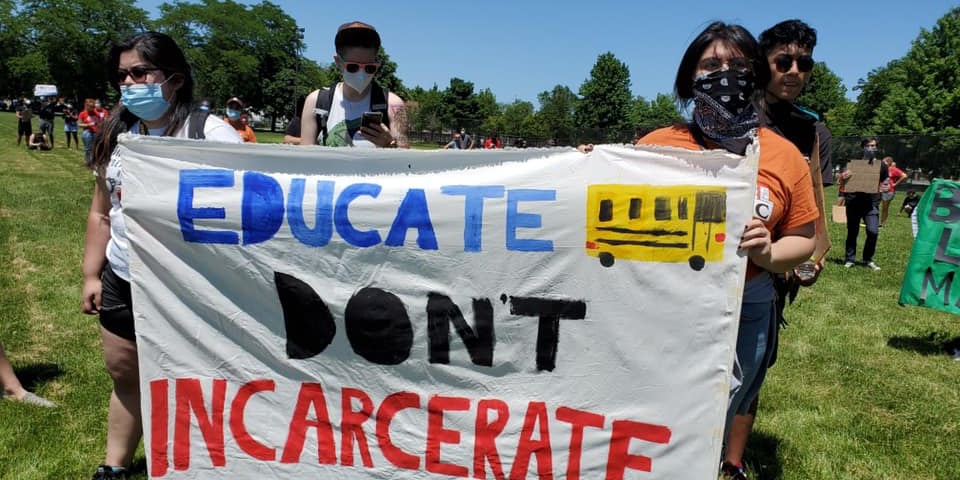

In recent weeks, the momentum behind removing School Resource Officers from learning environments, divesting local funds from police departments, and investing more in school health services has taken the country by storm. Ella Burrows, Operations/Partnerships Director of UrbEd, a non-profit focused on reimagining urban educational standards, told The Politic about the organization’s Police-Free-Schools initiative launched this year. Burrows noted that the launch of their new email campaign just last week has since led to almost a thousand call-to-action emails being sent to school leaders. From Seattle to Chicago to D.C., and anywhere in between, education activists are forming task forces and organized coalitions to address the detriment of hyper-militarized school climates and communities by advancing research studies, policy advocacy, and social media coverage.

In fact, several major school districts across the United States have addressed and even adopted plans to remove the presence of law enforcement within school buildings. In a June 19 Hechinger Report article, education reform advocate Elona Wilson elaborates on Portland (OR) Public Schools’ recently-adopted plan of action to discontinue partnerships with its communities’ School Resource Officers. It almost directly follows Minneapolis public schools’ decision to end its relationship with the city police department as a result of the injustice and hatred displayed by the officers in uniform who murdered George Floyd.

However, these progressive and localized policy reforms were adopted primarily as a result of our nation’s current state. It would be too idealistic to assume students, teachers, and advocates alike had not already recognized the negative impacts of promoting systems of penalization in learning settings long before the events of the past several months came to light. Students of public schools in Portland have been active in campaigns and on social media for the past two years trying to remove SROs from their schools. In Chicago, a coalition of organizations under the title Cops Out CPS produced in-depth research, with data spanning the past decade, supporting the need to dissociate Chicago Public Schools from law enforcement officials (LEOs).

The serious lack of oversight and accountability within police departments across the country has existed for decades now, and the nation’s collective repulse against police brutality caught on camera has only led to increased awareness of the issues at hand. Policy makers have for far too long placed priority on maintaining law and order over practicing justice—a child’s educational environment is one of the first places to rectify this failure.

Right now, the majority of our public schools value penal repercussions over rehabilitative services, and America’s historically underserved students continue to be disproportionately afflicted. As it stands, The ACLU reports “1.7 million students are in schools with police but no counselors. Six million students are in schools with police but no school psychologists, and ten million students are in schools with police but no social workers.”

According to data compiled in 2016 and released in 2018 by the United States Department of Education, 47 of America’s 50 states do not meet the recommended student to counselor ratio. Set at 250:1 by The National Association for College Admission Counseling (NACAC) and the American School Counselor Association (ASCA), this proportion is only met by New Hampshire, Vermont, and Wyoming. This sends a clear signal that America’s recent shift in student safety and well-being protocol has strayed from the goal at hand. Students, particularly those from first-generation, low-income, and regionally remote backgrounds necessitate the support of counselors in their efforts to learn, grow, and transcend systems of hardship with higher education’s promises of social mobility.

In addition, 3 million students report attending school where police officers were present but nurses were not. This ACLU report continues by pointing out more than half of states across America do not meet the recommended nurse to student ratio of 750:1, as per the National Association of School Nurses. This is a critical shortcoming in American public education that must be addressed on a nationwide scale—until then, youth-led organizations are leading the way in redefining student safety and health within specific school districts in hopes of promoting policy that can benefit any public school in America if adopted.

According to the Cops Out CPS report updated on June 22, “the $33 million currently allotted to 180 SROs in CPS could fund positions for 317 social workers, 314 school psychologists, or 322 nurses.” Another case example: Philadelphia’s police-in-schools budget is increasing from $29.9 million in fiscal year 2019-20 to $31.3 million in fiscal year 2020-21. The same documents display funds for counselors, nurses, and psychologists as a lump sum—this amount of around 70 million dollars is substantially less than the approximate 90 million that theoretically should be cumulatively allocated to the three positions. It is detrimental, in this case, for the School District of Philadelphia to refrain from differentiating the funding of these three positions in school systems because in doing so, schools fail to identify the importance of each resource as individual but equally necessary components to ensuring student health. State and local decision-making boards in Pennsylvania and around the country are able to overlook the very real truth that police positions are proportionally funded more than the individual counselor, psychologist, and nurse positions in schools.

This is why we have to recognize “defunding the police” is not as scary as it seems. Mariam Khan ‘24, of Hamden, CT, commented on the necessity and feasibility of defunding police departments with proven budget surpluses and returning those funds to the community in the form of education. “We have been defunding necessary and important aspects of life regularly, without a problem, and ‘defunding’ wasn’t a scary word there… [but] policing is related to fear.” Khan recounted an instance in Hamden Middle School in late 2018 where a school resource officer observed a student enter the principal’s office and proceeded to make unsubstantiated assumptions, taunt the student, and prevent the student from calling his grandmother when he requested. This kind of policing does nothing to create a welcoming environment for students of color.

The argument that punitive systems and their enforcers are necessary in schools to defend against gun violence falls because police aren’t actually new developments in response to safety. The first school resource officer programs were instituted in Flint, Michigan, in hopes of bringing police and students on closer terms. The presence of police in predominantly Black and Brown communities have always been more prevalent than in affluent neighborhoods and public schools. Only in the 1990s did the movement to expand the presence of law enforcement in schools gain momentum. In 2018, after the Marjory Stoneman Douglas tragedy, school boards and state governments across the nation began confronting the issue of school safety even further.

However, urban schools were overrun with punitive elements long before legislation addressing gun violence in schools compounded police presence in all educational settings. Despite the intent of promoting school safety, those policy decisions have exacerbated “zero-tolerance” punishments that disproportionately affect students of color and have done nothing to diminish the school-to-prison pipeline. Also, analyses of about 200 school shooting cases found police to have successfully mitigated situations only twice. Considering the amount of public funding poured into school safety institutions, a 99 percent rate of error in addition to the constant threats police pose to students of color only leaves room for their removal.

GenZ and Millennial activists have been at the forefront of advancing this effort, and have done so by utilizing the pen—often mightier than any weapon. Students and organizers in the Washington D.C. metropolitan area have turned to essays and poetry to dictate what impact police divestment can turn into for hyper-policed urban communities across the nation.

An excerpt from an essay by Naomi Chasek-Macfoy, a D.C. organizer for Black Youth Project 100, reads, “the call to defund the Metropolitan Police Department is a call for the urgent transformation of the daily conditions of Black life toward new conditions of safety and liberation. Real safety lies outside the harassment and surveillance of policing. It lies outside of caging and imprisonment…. We must reject the punitive posture of law enforcement and instead adopt an approach rooted in redistributing resources and cultivating relationships with friends and neighbors.”

Similarly, Samantha Paige-Davis, founder and Executive Director of D.C.’s Black Swan Academy, wrote, “We know that police do not keep us safe and, in fact, cause more harm. Black girls in D.C. are 30 times more likely to be arrested than white youth of any gender identity. 60 percent of girls arrested in D.C are under the age of 15, and many of them are disciplined and referred to police for their responses to experiencing sexual violence.

The youth demand is simple and clear: Love us, don’t harm us.”

There are three key areas of reform to focus on when it comes to mitigating and eliminating the excessive uses of force that pervade educational settings in particular. The first step is to simply defund and divest recognizable police funding surpluses, especially in communities that are known for massive patrol units and massively underfunded per student public education funds. The second step towards healthier school environments year-round is to recognize that the increased presence of officers in school settings without additionally prioritizing the essential service of counselors, nurses, and therapists is naturally counterintuitive to securing student safety. Ideally, surplus funds originally dedicated to policing will in turn be utilized to bridge the gap in schools where students have reported the presence of School Resource Officers (SROs) and no mental or physical healthcare professional.

The final course of action is to establish systems of justice and behavioral reform that actually strike a chord with and aim to rehabilitate students and their communities—a proven course of action being Restorative Justice (RJ). This disciplinary practice does not focus on depriving the student of a privilege or suspending a student from school to learn from a mistake. Instead, the goal of Restorative Justice is to eliminate zero-tolerance policies that inherently teach students to disbelieve in the school establishment while also keeping them from realizing their educational potential. RJ encourages conversations between the student and the school community about the causes and implications of behavior that is not in accordance with school rules. This alternative to punishment has been successfully implemented in various settings around the world and across the United States. Students who experience this system that genuinely invests in personal improvement are better prepared to leave their educational upbringings and address a world that, in time, will no longer assume the worst for them based on “the zip code they live in and the color of their skin.”