“I think a lot about violence,” she says. Behind her, her son breaks her daughter’s pottery animals into a thousand pieces.

Girls and Boys, a one-woman play by Dennis Kelly, premiered at London’s Royal Court in February 2018 and moved to Off-Broadway in June 2018. The play centers on an unnamed woman, “Woman,” played by Carey Mulligan, who finds her way into the film industry, has two children with her husband, before her life teeters into tragedy.

Girls and Boys alternates between “chats” and “scenes.” In the “chats,” Woman stands in a white box, void of props or a backdrop. She directly addresses the audience, sharing stories of travelling the world–“Paris is a dump”–, meeting her husband-to-be in the queue to board an easyJet flight, and falling in love with his “ridiculously articulate” hands.

In the “scenes,” the white box falls away, and Woman is in a well-furnished home. This home is awash in a pastel blue light. Everything is blue, baby-boy blue. An island table punctuates the kitchen, ornaments and books decorate the shelves lining the wall, milk bottles and children’s toys litter the floor. Here, Woman no longer addresses the audience. Instead, she begins to interact with unseen presences on stage–her daughter Leanne and son Danny–, chastising Leanne for bringing a bucket of mud into the house, cleaning up after Danny spills food over himself.

As Woman plays “Architect” with Leanne and then “Terrorists” with Danny while Danny drops a pretend nuclear bomb on Leanne’s imaginary skyscrapers, the thesis at the heart of Girls and Boys becomes apparent: girls create and boys destroy.

As the play unfurls, this thesis takes a brutal turn. Woman’s husband is not pleased that she is attending film award ceremonies as he folds up his antique wardrobe business. He stops engaging, stops trying, stops caring. Woman asks for a divorce. He relents and everything is okay, until he decides to plunge a Kandar GX208 hunting knife through both his children’s chests.

It is then that we understand that Woman’s children are invisible not for just stylistic reasons. No–they are invisible because they are dead.

This living space washed in blue is a kind of twilight zone in Woman’s memory, one that represents a past now gone. The stage gives the audience, uncomfortable voyeurs, access to that place, as Woman continues to revisit it.

Girls and Boys recalls contemporary literature on the construction of gender. In her article “The Metaphysics of Gender,” Elizabeth Barnes poses the question: What does it really mean to be a woman? Or a man? Or genderqueer? Is it your body? Your personality? How others perceive you?

The play offers one answer: that to be a man is to have a proclivity for violence. That boys want to destroy their sister’s toy skyscrapers and wield a toy gun because they are boys. Woman tells us that family annihilation happens “more than [we] think,” that 95% of people who annihilate their family are men.

Girls and Boys recalls examples in art, literature, and the news where women endeavor to acknowledge, comprehend, and recover from violence inflicted by a man. In Paul Verhoeven’s Elle (2016), Michele Leblanc, played by Isabelle Huppert, spends the entire film searching for the masked man who broke into her house and assaulted her; in Speak (2004), fourteen-year-old Melinda Sordino, played by Kristen Stewart, stops saying anything after a senior student rapes her; in TV series Big Little Lies, Celeste Wright, played by Nicole Kidman, wrestles with how her husband hits her, just sometimes, in their beach-home marriage that otherwise resembles a postcard.

In these examples, we observe these women from afar. We wince behind a screen and press pause; we swim in our moral emotions. In Girls and Boys, however, Woman takes away our immunity. By speaking to us, she addresses us, implicating us in the her narrative.

“We didn’t create society for men,” she says. “We created it to stop men.”

Here, Kelly presents a twist to the Hobbesian state. He suggests that civilization is invented to tame the brutish instincts of not all human beings, but of men specifically. The men in the audience shift in their seats; a few women fold their hands on their lap, as they are forced to wonder: “my husband would never do that… right?”

We could, on the one hand, cubby-hole Girls and Boys into the category of a “radically feminist play,” dismissing it for purporting “radically feminist” perspectives that are not objectively true. It would be misguided to think that all men are violent, right? The Guardian’s review laments that the play just presents “one side” of the story and that its singular perspective reduces its credibility.

However, I argue that the play’s radical subjectivity is its greatest strength; that for once, an audience of all genders is held captive to a woman’s authority–authorial for its exclusivity, for its refusal to acknowledge that there is any other side to this story, for its laying claim that her story is the story.

As she tells her story, we live in her body. As she shows us where exactly her husband stabbed her children–back of the left shoulder, upper stomach, lower chest, right of heart– we feel the knife in our bodies too. We witness her find reprieve in her mind; we watch her make believe. We are glad it is not us. Yet the play presents audiences with the unsettling reality that to certain women, this play is not fiction. And that as we, holding our breath, watch Woman build a skyscraper of a life, a skyscraper elsewhere crashes to the ground.

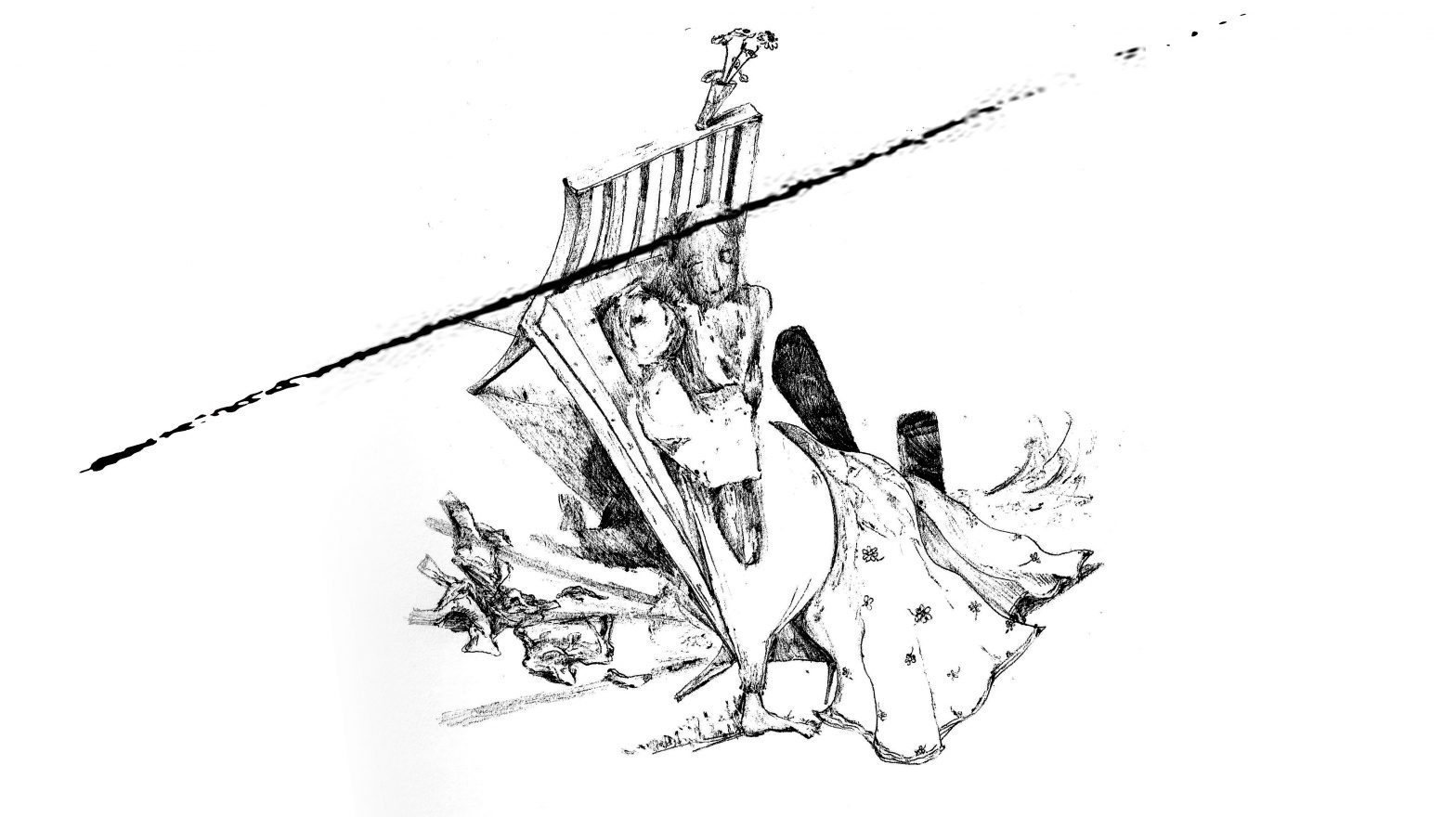

Illustration by Itai Almor ’20, a junior in Saybrook College.