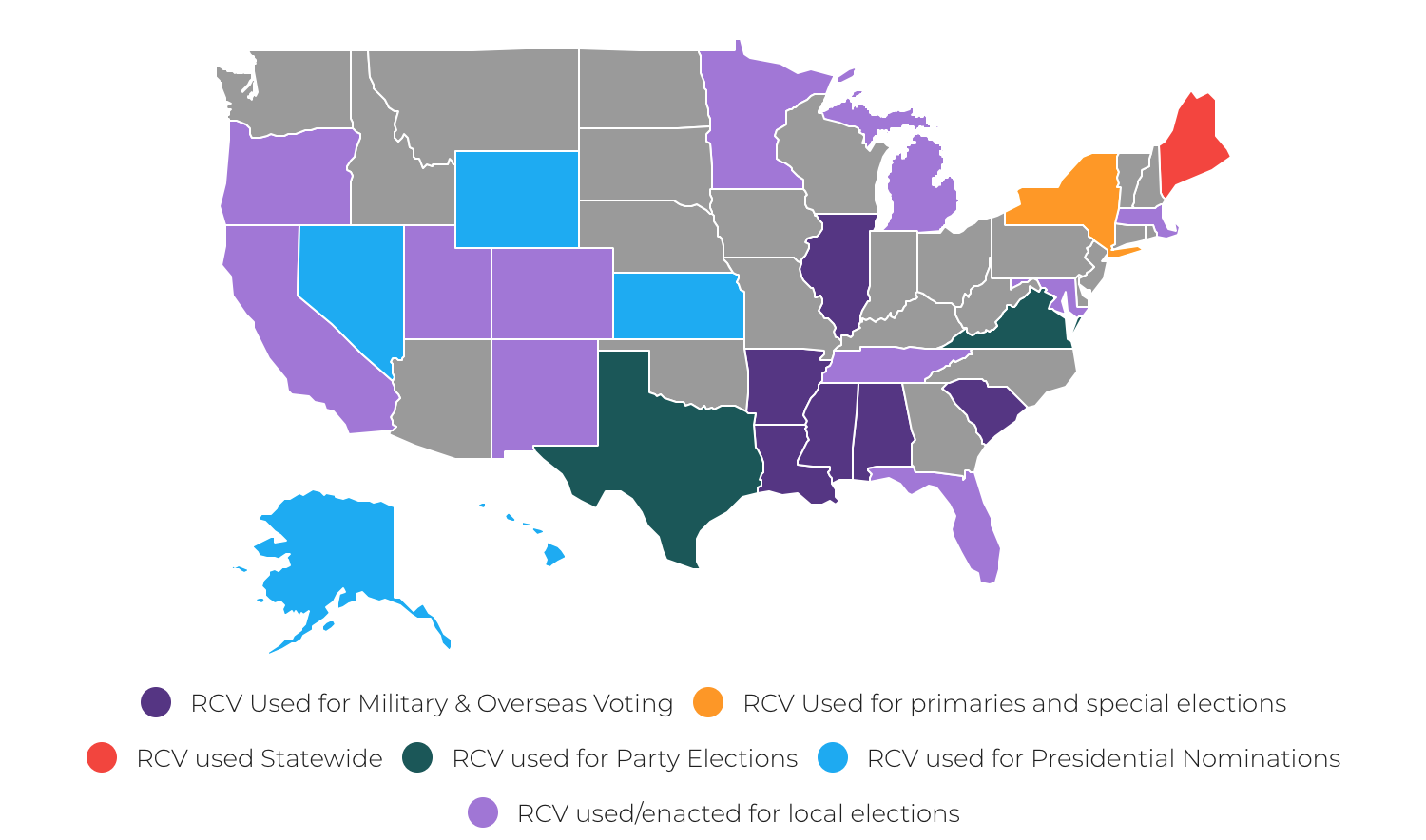

In the 2020 election cycle, cities across America voted to implement ranked choice voting (RCV) in their electoral process. Many cities and states, including Maine and Alaska, already use the system, or have voted to implement it but have not yet done so. Maine is currently the only state that has adopted RCV, but it is joined by cities like San Francisco, Santa Fe, and Minneapolis. Outside of America, RCV enjoys widespread use in Australia, Ireland, New Zealand, Malta, Northern Ireland, and Scotland. So, what is ranked choice voting, and why is it gaining popularity?

Ranked choice voting is an electoral system in which voters rank candidates on their ballots, rather than just choosing one. After the votes are tallied, if a candidate has received more than 50 percent of the first-choice votes, he is declared the winner. However, if no candidate meets the 50 percent mark, the candidate with the fewest first-choice votes is eliminated. The second-choice votes on that candidate’s ballots are distributed to the other candidates, and votes are again tallied. The process repeats until a candidate has a majority of the votes. Ranked choice voting is also known as instant run-off voting.

The system has faced support and opposition almost exclusively along partisan lines, with Republicans strongly opposed to the practice and Democrats typically supporting it. This divide makes sense. Two of the most well-known elections brought up in favor of RCV are the 2000 election and the 2016 election. In both of these elections, “spoiler” candidates prevented Democrats from winning the presidency. Had RCV been implemented in 2000, third-party candidate Ralph Nader’s votes would likely have gone to Al Gore. In 2016, Green Party candidate Jill Stein’s votes would have been counted toward Hillary Clinton, and may have helped her win. In both of these elections, there is a reasonable case to be made that single-choice voting benefitted Republicans.

Despite opposition, many aspects of ranked choice voting seem objectively positive. For example, the entire premise of RCV is based on the idea that many candidates are elected with a plurality of votes, but not a majority, leaving more than half of voters dissatisfied with the results of any given election. In theory, RCV ensures that any candidate elected has at least some support from a majority of voters.

RCV also promotes more positive and broader campaigns. Because candidates can still earn the second- or third-choice vote from voters with a different first choice, they should be less likely to run a negative campaign against their competition. It will be in candidates’ best interests to alienate as few voters as possible and to campaign beyond their core base. Candidates could theoretically campaign together to diverse groups of voters, petitioning to be either their first- or second-choices.

In recent elections, notably the 2016 and 2020 general elections, many voters have felt an obligation to vote for the “lesser of two evils.” RCV proposes a way to end this phenomenon and to allow voters to choose candidates they actually support by offering more options, even without dismantling the two-party system. RCV should also help third-party candidates win elections and gain prominence by eliminating the spoiler effect mentioned earlier. In 2020, Democrats strongly urged progressive voters not to support third-party candidates, arguing that it was more important to remove President Trump from office than to support the best candidate. For the most part, they made a reasonable argument for the current electoral system. A vote for the Libertarian or Green Party was, in most cases, a vote taken from Biden. RCV would allow voters to rank their favorite candidates first, regardless of their odds of winning, without fear of “throwing their vote away.”

In cities where it has already been implemented, RCV has proven to increase the number of women and minority women elected, likely the result of voters trying to balance their ballots with a mix of men and women. The system would also likely favor centrist candidates, which may seem like bad news for progressive readers, but which could help end the partisan divide in modern politics. A desire to appeal to a broader base may also lead more radical candidates to moderate their ideas and may encourage more centrist or independent candidates to run.

Despite its many apparent advantages, ranked choice voting poses a few potential problems. Because it is a slightly more complicated process, RCV could lead to invalid ballots if not supported with sufficient educational efforts. Voters would also need to research more than just two candidates in order to rank them accurately, which may be unrealistic for many. If voters instead only rank one or two candidates, their ballots may be “exhausted” after all of their votes are eliminated. In this case, their ballot would have zero impact—a fate, opponents of RCV argue, that is worse than voting for a candidate who loses.

Some proponents of RCV suggest that it could replace the primary process, but opponents argue that this new system, along with a lack of negative campaigning, could lessen the public vetting to which candidates are subject. This lesser level of scrutiny could allow unqualified candidates or candidates with negative histories, to be elected. It is worth noting however that almost every Democrat and many Republicans in America would argue that this worst-case scenario has already occurred, with a primary system and negative campaigns doing nothing to prevent corrupt politicians from taking office.

Ultimately, ranked choice voting is a worthwhile experiment in democratic reform. When it was implemented in Maine in 2018, it was largely seen as a success, and it has proven effective in cities across the country and in countries around the world. As with any major change to the electoral process, the change deserves significant investigation before it earns widespread implementation. Still, the large number of cities that have voted to implement RCV suggests a sense of optimism regarding the practice. Ranked choice voting may be the solution that America needs to lessen the partisan divide and ensure that voters’ voices are heard.