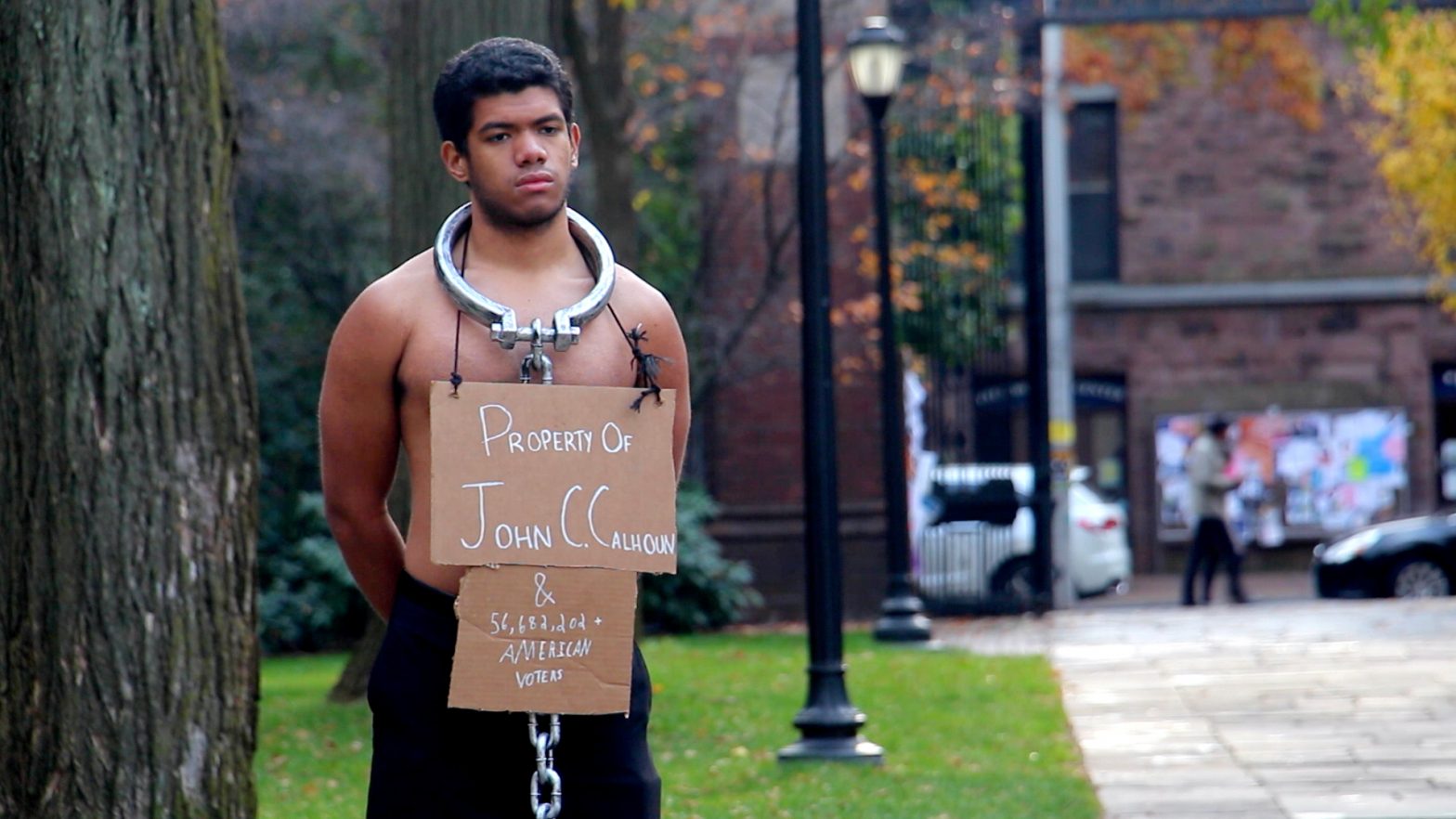

On November 9, when the world woke up to an election result that had been hard to expect and, for many, was even harder to believe, Branson Rideaux ’20 decided to stage a protest. Passerby saw him on Cross Campus, standing bare-chested, a chain around his neck with a sign reading “Property of John C. Calhoun and 59,930,946 American voters.” Rideaux sat down with The Politic to share the motivation behind the protest and his opinion on the implications of the vote.

The Politic: Why did you choose this particular form of protest?

Branson Rideaux: After the result, as I was sitting in the African-American Center I started wondering if there was anything I could do. I’m an actor so for me it was about how can I employ that to send my message and display my emotions about what happened. What I did was as much for myself, as it was for others; it was just important to me that I do something.

TP: Did the night of the election change how you think about this country?

BR: Definitely. I had a lot of conversations with people during the week and I was very optimistic. I’d say, “Trump will not win more than 35% of the popular vote because I don’t believe there is that many people who could support a campaign like his.” And I was wrong. The reason I put the popular vote on the sign, instead of just “Property of Donald Trump”, was because for me what hurt the most was that there is that many people in our country that this message of hate could resonate with.

TP: Do you think after these long months of polarizing, offensive campaign that we witnessed it is possible for the new government to be able to represent the voice and interest of all citizens rather than of their electorate?

BR: I think this election was also different because it was the worst possible time for one party, regardless of which one, to sweep both Congress and the executive branch, as they also get to decide the judicial branch. This system makes it hard for both sides to be represented properly in the government. I believe it becomes up to us now, as individuals, to appeal to those people who don’t share our ideas. The fact is that our view of the world isn’t going to be represented enough in public life so we have to make sure that we are vocal and that we still find ways to get our views out there.

TP: According to the exit polls 3% of African American and 17% of Hispanic voters chose to support Trump. How do you think it was possible, what can be a motivation for a person to choose a representative who repeatedly offended them?

BR: I think his supporters are just people who identify with his general message. No matter what aspect you’re looking at, whether it’s policy, or how offensive he is, it all revolves around hate, around resentment, around this feeling of abandonment. I think the reason why minorities still voted for him was that they had a similar feeling, whether that’s because of outsourcing of jobs, or because they feel the government has left them behind. It’s just the feeling he vocalized that resonates with them, even though he is offensive towards some parts of their identities.

I don’t think people who support him are wrong or bad, I think there’s some kind of environment and mindset that we as a country have facilitated and allowed to happen. And it’s just as much a fault of all of us. You cannot just blame it on the Trump supporters, you have to understand and ask why it is that they think the way they do. I wanted to show that just as much as it is our responsibility to change the name of Calhoun, it is our responsibility to try to change the fact that there are 59 million people who support the message of hate.

TP: Do you think the election changes the context for the discussions that emerged on campus last year?

BR: Coming here I didn’t care as much about the name changing, it was only after I realized that just like Trump, Calhoun is also primarily a symbol. And when you have these symbols of hate it just validates the negative feelings that people have. I think what we’ve seen in Trump is that legitimizing hate and ignorance encourages perpetuating these feelings.

TP: Did the result change how you personally feel on campus?

BR: The thing I thought about the most was how am I, as a person of color here, going to react. There are people all across the country who just don’t have the voice that I have because I was able to come to a place like this and be in a world that minorities are still not equally welcome in. What has happened now, just made my being here much more important. A few months ago I didn’t think of it that way, I assumed I’m just going to study and get a degree, but I realized there’s far more to that, especially now, that I must represent the people of color and give voice to those who don’t have the same opportunities and the same influence that I can have here.

TP: What do you think is now to do for those of us who imagined America in a different way than the result has shown?

BR: I was told that what I’ve done was divisive. How I would explain it was that “yesterday it was okay to be divisive,” and I do not mean yesterday only in a literal sense. It was okay to grieve, to be mad, to be angry. And for some it surely won’t be over for a while, the elections have shown some things that not all of us were ready to hear. But when that’s passed, it’s about figuring your place in what is happening. What you can do, and what you are responsible for doing. I think that especially because we’re at Yale, because we’ve chosen to say, “I’m going to be something impactful, I’m going to try to change something,” we are responsible to deal with it now. There are millions of people who don’t have the comfort of being in our position. It’s about finding your individual role in the chaos and figuring out how you choose to fix it, in big or small ways, even if it’s simply making sure you communicate a message of love and respect, not hate.