I grew up in rural Wisconsin in a small town with a population just over 3,000. The town rests at the bottom of a valley with a stream running through downtown and a single four-way stop on Main Street. We live on the edge of the city, where houses fade to family farms that stretch back through the generations. Growing up, I was raised with small town hospitality and a strong sense of roots. My state may have been led astray in the 2016 election, but I was still proud of its past. Wisconsin had led the progressive movement, became the first state to ratify the 19th amendment recognizing women’s suffrage, and passed the first statewide anti-discrimination law in the country. But, despite its progressive legacy, Wisconsin, like many states in the Midwest, had a history that never made it into the curriculum—sundown towns.

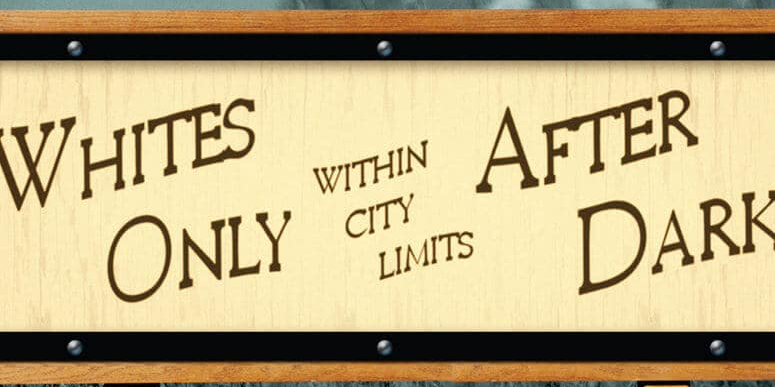

97 percent of my community identifies as white. My town was likely one of the hundred cities across Wisconsin that were once known as sundown towns—all-white communities that, either formally or informally, excluded African Americans from settling in town or staying after sunset. Between 1890-1970, the Midwest had the highest number of sundown towns in the nation; Wisconsin alone once had an estimated 100. Signs posted on the city limits warned black visitors to keep their distance after dark. One outside Manitowoc, Wisconsin included a racial slur followed by the threat, “don’t let the sun go down on you in our town.” Those who didn’t obey the sign were often forcibly removed by white supremacist groups that used threats and violence to run black families out of the city, sometimes with the help of local law enforcement.

It wasn’t just small towns either. Sundown towns soon spread to sundown suburbs, like Edina, Minnesota, a wealthy suburb on the outskirts of Minneapolis. Edina was originally founded by black families, but, in 1924, the surrounding land fell into the hands of Edina’s Country Club which turned the town into one of Minnesota first planned communities with the informal motto “Not one Negro and not one Jew.” By the 1930s, most black families had left Edina and moved back to Minneapolis or into more welcoming communities in other parts of the state.

All-white towns, like mine, are no accident in the Midwest. The sun may have set on sundown towns, but the relics of racism linger. Despite its history as the heartland of progressive politics and the stereotype of Midwestern nice, Wisconsin, and particularly small town Wisconsin, still bears the scars of segregation. “Racism with a smile,” is how Leila Ali, a Somali immigrant and resident of Minneapolis, described it to The New York Times.

Like Minneapolis, Madison is a liberal bastion with politics as deep blue as the lakes surrounding the city. Residents boast of the miles of bike paths, America’s largest farmer’s market, the ardent student activists, and one of the highest concentrations of nonprofits in the nation. But, Madison is as fraught with racial tension as the rest of the country. Black adults represent just 6.7 percent of Wisconsin’s population, yet they make-up 42 percent of inmates. In Dane County, one of wealthiest counties in the state, almost three-quarters of black children live below the poverty line. In 2011, only 50 percent of black students graduated high school within four years and were only half as likely as their white peers to take the ACT or SAT. In fact, a 2014 report by the Annie E. Casey Foundation ranked Wisconsin as the worst state in the country for black children. For black students seeking opportunity, Wisconsin was one of the worst states to be.

Last Tuesday, protesters in Madison tore down two historic statues outside the state capital: a statue of Col. Hans. Christian Heg, an anti-slavery activist and Union soldier who died fighting the Confederate army, and the “Forward” statue, a bronze sculpture of lady liberty with her right arm extended in a symbol of progress and devotion. In a tweet, Wisconsin Assembly Speaker Robin Vos condemned the violence, calling the destruction “despicable” and criticizing Governor Evers and Madison officials for failing to “deal with these thugs.”

But, for protesters, the statue was a reminder of white liberal hypocrisy. The greatest outcry over the statues’ destruction came from proud progressives, those who vote Democrat, attend Black Lives Matter marches, and applaud the fall of Confederate monuments. And yet, many are unwilling to confront the legacy of slavery in their own backyards.

Two days after the statues fell, Althea Bernstein, a biracial 18-year-old woman from Wisconsin, was attacked by a group of white men who yelled the N-word at her, doused her in lighter fluid, and threw a lighter through her car window causing the liquid to ignite. Bernstein sustained second- and third-degree burns on her cheek and neck. The Madison police and FBI are investigating the attack as a hate crime.

As Ebony Anderson-Carter, a spokesperson for protesters, told Channel 3000, “We’re not moving forward, we’re moving backwards. This [statue] doesn’t need to be here until we’re ready to move forward.”

By mourning the destruction of the statues, we are mourning the myth of progressivism. Madison’s liberal bubble hasn’t just insulated us from Trump’s bigotry. It’s allowed us to turn a blind eye to racism within our own city. The spirit of Wisconsin progress, embodied by the “Forward” statue, only applied to part of the population. For black residents, the state has failed to live up to its motto.