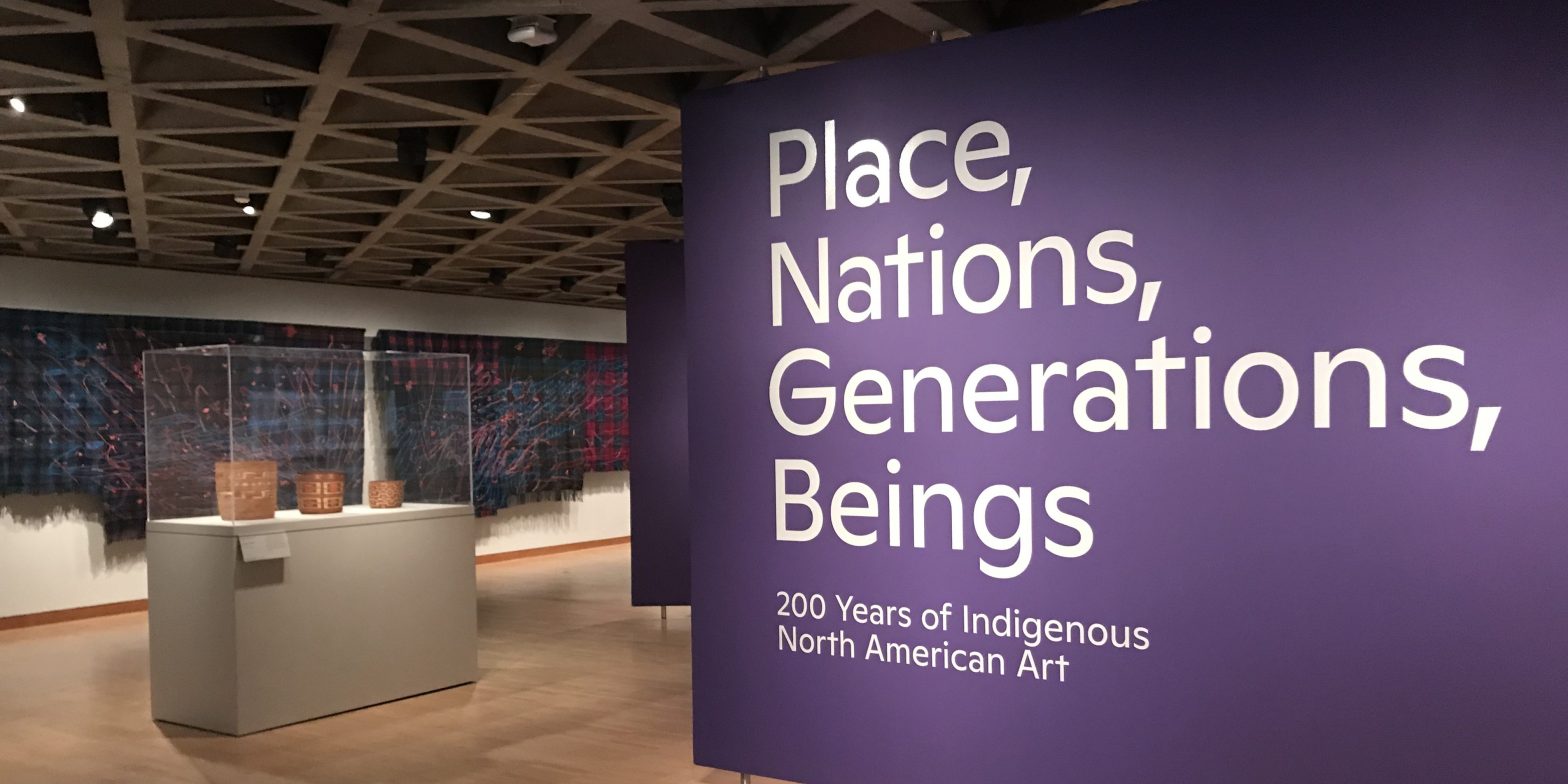

Warm light filters through the gallery, illuminating an array of intricate beadwork, embroidery, carvings, weavings, ceramics, and prints. The entire display feels as intentional as each individual piece of art. Colorful wooden panels partition the space, guiding visitors through the exhibit and encouraging them to place individual works in conversation with one another. Striking a balance between a formalist and ethnographic display, the rather unconventional structure of the exhibit is quite freeing; it centers individual works while also inviting visitors to consider how each unique story can be woven together. In more ways than one, the exhibit demonstrates ground-breaking challenges to traditional representations of North American Indigenous art.

On November 1, 2019, the Yale University Art Gallery (YUAG) unveiled a new exhibit entitled Place, Nations, Generations, Beings: 200 Years of Indigenous North American Art, Yale’s first major exhibition of Indigenous North American art. The installation was curated by three former students: Katie McCleary (Little Shell Chippewa-Cree) ’18, Leah Shrestinian ’18, and Joseph Zordan (Bad River Ojibwe) ’19, and showcases works from the 19th century to the present from over 40 Indigenous Nations. The exhibit also represents an interdisciplinary and university-wide engagement with Indigenous art, as the pieces were collected from The Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, the Beinecke Rare Book Manuscript Library, and the YUAG.

Prior to the exhibit, Indigenous art was almost non-existent on campus. With the exception of only a handful of pieces in the YUAG, Indigenous works were predominantly stored in The Peabody. The lack of visibility of Indigenous art on campus was shocking to students who were raised in Indigenous communities. In an interview with The Politic, McCleary described growing up on a reservation in Montana, where she was surrounded by Indigenous art made by her family and community. She recalled, “coming to the East Coast was pretty jarring because Native people are so erased.”

Until 2017, The Peabody offered an exhibit entitled The Hall of Native American Cultures, which displayed Native objects after visitors walked through a series of exhibits featuring dinosaurs, mammalian evolution, and human origins. As the student curators expressed in the catalogue of their exhibit, “this path conveyed a confused notion of evolution, in which Indigenous cultures were a step in the history of humankind.”

The Indigenous community at Yale has been discussing how to improve representation for decades, and the student curators cited the influence of generations of Indigenous activists that came before them. According to McCleary, “the impetus for this project came from Native students and staff pushing The Peabody and the YUAG to better present Native art.” Displaying Indigenous works within an art gallery as opposed to a natural history museum changes the ways that visitors approach the works, as the pieces are perceived as works of art rather than as artifacts buried in the past. As Zordan emphasized, in an art museum, “there is a more immediate sense of respect.”

In addition to improving visibility and representation, there was a desire within the Indigenous community at Yale to challenge the settler colonial practices of collecting and presenting Indigenous art and bring awareness to Yale’s engagement with these practices. Historically, government policies that forced Indigenous containment made the collection of Indigenous artifacts readily accessible to settler scholars, and the process of Indigenous relocation legitimated settler claims to Indigenous land and material cultures. Therefore, even ‘legal’ purchases of Indigenous objects are often tied to settler colonial policies and assimilationist practices. In previous representations of Indigenous art at Yale, there was not an explicit acknowledgement of this history, which further contributed to its erasure.

In 2017, the YUAG asked McCleary to design and curate an exhibit dedicated to North American Indigenous art. The proposal came as a result of McCleary’s participation in Yale’s Native American Arts Internship in 2016, co-sponsored by The Peabody and the YUAG. This internship allowed students the opportunity to present original proposals outlining how both institutions could better collect and display Indigenous art.

McCleary presented the exhibition proposal to Shrestinian, who also participated in the internship, as well as Zordan, who was working as a Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) assistant at The Peabody. At first, the trio was uncertain that they had adequate experience to take on the project. While they were excited by the idea, they also believed that the YUAG should invest in hiring a professional Indigenous curator for the project and form an advisory council of Indigenous artists and scholars.

However, the students’ desire to improve representation of Indigenous art outweighed their initial qualms. From the beginning, McCleary emphasized that “this project has always been about increasing visibility, better representing Native people, and having the opportunity to better educate non-Native people about our societies, knowledge, and cultures.”

When discussing issues of representation, the students also considered the significance of displaying Indigenous art in spaces where it has been traditionally excluded or ignored.

“Now, it’s a question of who is benefiting from Indigenous art being on display and [from] being a part of this art historical narrative. It’s a really complicated question,” Zordan explained.

Eventually, he also decided that the art should be showcased, primarily out of a desire to increase awareness. “It’s a powerful thing to feel seen, and especially powerful coming from other students,” he said.

To ensure that Indigenous students at Yale felt represented in the exhibit, the curators sought the input of a Student Advisory Committee, consisting of about 15 students. Madeleine Freeman (Choctaw and Chickasaw) ’21, a member of the Committee and a gallery guide at the YUAG, explained that the exhibit sparked more discussions about representation and other Indigenous issues. Through her involvement with the exhibit, Freeman had the opportunity to give a tour with Shrestinian about the different ways in which the YUAG could improve their portrayal of Indigenous art that was showcased elsewhere in the gallery. She also continues to educate others by giving specific highlight tours of the exhibit.

The exhibit is guided by four themes—Place, Nations, Generations, and Beings. Upon entrance to the exhibit, visitors first walk through the ‘Place’ section of the exhibit, where they can begin to consider what the works reveal about the significance of land to Indigenous peoples. Most of the artifacts were collected between 1870 and 1930, when Indigenous North American peoples were often forced from their homes, so many of the pieces speak to that experience. Shrestinian reflected, “we wanted to think about the significance of Native people’s relationship to place and the effects and violence of displacement.”

According to Shrestinian, sourcing the artifacts was an extremely emotional process. For instance, many of the pieces were not stored appropriately, found inside wooden drawers in The Peabody that had swelled shut in the summer. Additionally, the curators wanted to ensure that they were only using artifacts that Indigenous Nations wanted them to display. As a result, they steered clear of artifacts that were sacred, and requested permission from a representative of each Nation before the artifacts were put on display.

While the exhibit was designed to more accurately reflect the diversity of Indigenous stories, the curators also wanted to make the exhibit accessible to non-Indigenous people and provide a vocabulary to talk and think about Indigenous art and experiences. Language, as Shrestinian described, “is one of those areas in which you could see that balance or tension coming to life.” She explained that Indigenous sovereignty is a crucial theme in Indigenous studies, but that they were advised by their editor and others at the YUAG to use the word nationhood instead of sovereignty because the concept of Indigenous sovereignty can be more difficult to grasp. However, Shrestinian explained that they decided to maintain the original phrase in their exhibit because “that was something we felt was really important both to us and to Indigenous audiences.” McCleary added, “for Indigenous audiences, we wanted them to feel well-represented in the space and feel accurately spoken and written about.”

While Place, Nations, Generations, Beings is the first university-wide project to invest in Indigenous art, the curators hope that it won’t be the last. Beyond a single art exhibit, McCleary envisions an Indigenous North American art department at the YUAG, more Indigenous curators, and increased institutional support for tenure-track positions for scholars of Indigenous art. Ultimately, the curators see their exhibit as part of a broader conversation; as McCleary underscored, “investing in Indigenous studies should be a university-wide initiative.”