Bounded by the massive Mojave and Sonoran deserts, the Colorado River is known as the Lifeline of the Southwest. Winding from Colorado to Utah, through Arizona, and along the borders of Nevada and California, it encompasses 1,450 miles of flowing water. Traversing through labyrinths of deep sandstone canyons unique to the American Southwest, the river comprises a drainage basin of 246,000 square miles across the states of Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, Nevada, Arizona, and California. Yet in the face of historic drought and climate change, the mighty Colorado River is drying up.

On January 31st, the seven western states that utilize the Colorado River as a source of water failed to reach an agreement regarding how they would share the burden of cutting 2-4 million acre-feet of water usage per year. California is the lone holdout on agreement. As the original deadline was June 2022, this is the region’s second failed attempt to collectively reduce its water usage.

It now seems likely that the federal government will have to intervene and impose its own cuts on individual states. Currently, California and Arizona are at risk to lose the most water. Yet given Arizona’s status as a junior rights holder to the Colorado River, as opposed to California’s senior status, it is likely that the Grand Canyon State will have to bear the brunt of this burden.

“California has more senior water rights than Arizona. Arizona has this large canal, the Central Arizona Project, which runs 300 miles from the Colorado River all the way down past Tucson,” said Kristen Wolfe, coordinator for Arizona’s Sustainable Water Network, a coalition of 30 advocacy groups including the Sierra Club and local audubon societies.

The Central Arizona Project is how Phoenix receives its share of the Colorado River water. When the canal was built with the federal government’s money in the 1980s, Arizona agreed to junior water rights. While California could agree to more cuts, it doesn’t possess a legal obligation to do so.

Encompassing Phoenix, the fastest-growing metropolitan area in the country, as well as numerous rural areas that have already experienced well-depletion, Arizona faces tough decisions moving forward. The state receives 2.8 million acre-feet of water per year from the Colorado River and currently stands to lose 20% of that access. One acre-foot, which is equivalent to 326,000 gallons, is sufficient to supply water to three families per year. Last year, the state was forced to cut 512,000 acre-feet from the Central Arizona Project and is looking at similar cuts this year, on top of the 2-4 million acre-feet that the seven states must collectively give up. While these cuts shouldn’t affect citizens’ access to water, future ones could lead to water shortages in metropolitan areas if the Colorado River continues to dry up. High-density populations coupled with booming agriculture industries in the desert region will spur these water shortages.

“For most of the century, there was more than enough water feeding into the Colorado River system to meet all needs and allocations. The usage gradually grew through the 20th century,” Bob Henson, a meteorologist from Colorado and writer for Yale Climate Connections said. “By the end of the century, usage had pretty much caught up to availability.”

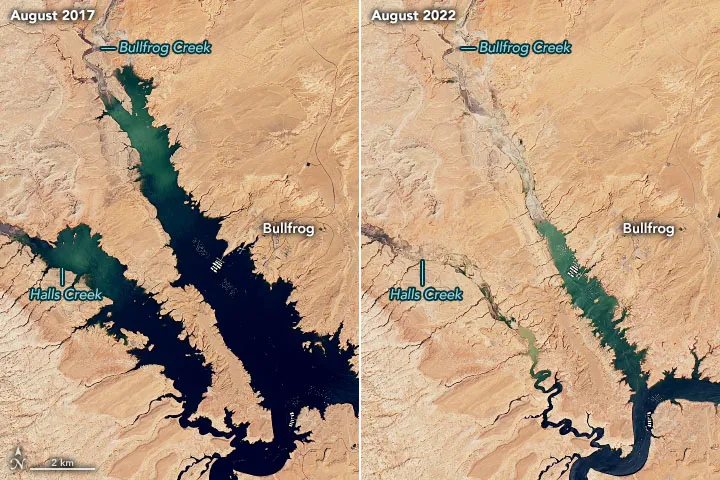

Between 2000 and 2020, the flow of the Colorado River averaged 13.4 million acre-feet per year, while consumption averaged 15 million acre-feet per year. Combined with the ongoing drought, the Colorado River has lost 33.6 million acre-feet of its total volume.

There are also concerns amongst environmentalists and meteorologists that 2023, an unusually wet year for the West, will distract people from the long-term issue at hand. Between October of 2022 and January of 2023, Flagstaff received two feet of snow above average; in Phoenix, the city received 1.23 inches of rain in January—the ten-year average for the month is around 0.75 inches. This past year of heavy rainfall and snow is not indicative of future wet years to come. Rather, it is an anomaly that may buy the region some time but is unlikely to repeat itself.

In fact, rainfall has not changed much within recent decades. Seasons are just becoming more extreme; wet years are getting more rain and dry years are getting even less rain than usual. Up until this past season, Arizona was in the midst of a dry spell that was exacerbated by rising temperatures. “What’s happening is that there are higher temperatures, which are absolutely related to climate change. That’s drying the landscape out, and the impacts of megadrought have been worsened by climate change,” Henson said.

Media coverage of water shortages doesn’t often highlight the struggles that rural communities face to obtain water. Currently, residents of cities like Phoenix and its suburbs are only asked to voluntarily reduce their water use, but nobody in these metropolitan areas deals with water rations. Meanwhile, some rural areas have already seen total well depletion due to droughts, and indigenous communities have dealt with water insecurity for decades.

“Water helps us clean things. When the pandemic hit, the people in the Navajo nation suffered greatly because there’s no running water up on Navajo tribal lands. We saw very clearly what happens when you don’t have water,” State Representative Stephanie Stahl Hamilton said.

As of 2021, 40% of Navajo households didn’t possess running water and had to travel several hours to outside areas to obtain water. With limited water reserves, Navajo families sometimes must choose between safe drinking water and frequent hand washing to prevent the spread of viruses. This meant that during the pandemic, the Navajo were at greater risk of exposure to COVID-19. With more intense droughts plaguing the Colorado River, Navajo people face heightened water insecurity and its consequences.

“I’ve read stories of neighbors fighting each other over water,” Auston Collings ’26, an environmental studies major from Tucson, said. “Rural communities, specifically indigenous communities, in Arizona have a very long history of water problems and inequity.” While the average American household uses 88 gallons of water per day, indigenous families only use three to four.

As it stands, Arizona is currently receiving about 40% of its water from the Colorado River. When it comes time to cut 20% of that amount, Arizona will have to reduce its total water usage by about 8%.

Given the economic benefits of a booming population—between 2010 and 2023, the state’s population has grown by over 15 %, jumping from 6.4 million to 7.4 million inhabitants—Arizona is reluctant to impose water restrictions on households, as these may disincentivize people from moving to the state.

Still, something will have to change, and it will likely be the agricultural industry. Farming uses upwards of 70% of Arizona’s Colorado River allocations. This may lead to the decline of some specific agricultural industries. For instance, the Yuma area in Southwest Arizona is a critical exporter of leafy greens across the nation. Other crops, such as alfalfa, are water-intensive plants used to support both the local and national cattle industry, but could easily be grown elsewhere in states not dealing with water shortages.

“Farmers need to do more of what they have been doing in trying to save water, and they have a very good history of implementing water efficient irrigation and adapting crops and the timing of their planting to reduce water use,” Susanna Eden, research program officer at the University of Arizona’s Water Resources Research Center, said. “As urban dwellers and citizens of the state, we may need to subsidize that ability for farmers, especially as so many farmers are working lands that they don’t own and don’t have the financial incentive or even ability to adopt conservation measures that require expensive infrastructure.”

Moreover, the agricultural industry’s water usage extends beyond the Colorado River. Farmers also have a complicated history with groundwater, and its depletion has another set of ramifications. Groundwater provides base flow to rivers, so when its supply is diminished, rivers go dry, a phenomenon already being witnessed in areas around San Pedro, Santa Cruz, and Tucson.

“They’re trying now to do more groundwater pumping, to supplement. [The agriculture industry] agreed back in 2007 to take less priority cap water as they try to find new sources, and they didn’t move on it,” Wolfe said. “So now they’re trying to supplement with groundwater, and groundwater is another whole different animal here in Arizona in terms of depletion.”

The problems of the Colorado River cuts and the issues revolving around the agricultural industry beg the question: what is the Arizona legislature doing to conserve water? By and large, the answer is nothing.

“In 1980, our groundwater management act passed. It was groundbreaking in many respects; it finally regulated groundwater in our most populous areas. And that was fantastic. It really did set us on a course of sustainability for our most populous areas at the time,” State Senator Priya Sundareshan said. “But now, it’s been over 40 years, and the state has grown. And we’ve grown into those more rural areas. Those areas were left unprotected back in 1980. That’s the problem. That’s one of the major problems that we need to be fixing, that we still haven’t been able to.”

Water is a highly politicized issue in Arizona, where Republicans currently control both branches of the state legislature and Democrat Katie Hobbs acts as governor. While a lot of legislation gets proposed, most bills never move forward. For example, during the past five years, Arizona Democrats have been trying to pass a watershed health bill, but it has yet to receive a hearing. Many politicians act in favor of the cattle and ranching lobbies and don’t want to see legislation pass that creates change for those industries.

“The unfortunate part is, there’s a little appetite for change,” Hamilton said. “It’s not only highly politicized, but it has fallen on partisan lines. It didn’t matter what bills we submitted to address the effects of climate change, to take care of greenhouse gas emissions. Those bills never got heard in committee. The decisions are still being made by agriculture and their own industry.”

Arizona might be able to successfully manage its water supply through conservation efforts, such as building solar panels over crops to prevent evaporation, capturing rainwater, and curtailing industries that misuse water. These preemptive measures proposed by Democrats would not harm the environment, nor would they take water from new sources.

Yet, in spite of these proposals, there are still politicians throughout the state floating impractical ideas such as desalination plants or piping water across the country from the Mississippi River—which has also been experiencing low water levels—if water insecurity becomes too severe. Under former Republican Governor Doug Ducey and the Water Infrastructure Finance Authority, Arizona allocated $1 billion dollars in 2022 to investigate these potential out-of-state water sources.

“A lot of money is earmarked for finding how we can import water from somewhere else. There’s talk of shipping water from Mississippi out here to the West, which from an environmental aspect is beyond ridiculous,” Wolfe said. “So when the Mississippi floods there should be a giant pipe that could suck that water across half the continent and alleviate water issues here in the West. Everybody calls that a real pipe dream.”

Republican legislators have also suggested building desalination plants on the Gulf of California, where salt water would be purified into fresh water and then pumped to the Phoenix area. This would involve hundreds of miles of piping, five to ten years of labor, and billions of dollars.

“It’s very interesting and quite frustrating that the state allocated a billion dollars to look into importing water from outside of the state and only 200 million for conservation,” Wolfe said. “So that alone tells a story. The legislature seems to be banking on finding water elsewhere versus making serious cuts within the state.”

Legislators often act without the interests of the most deeply affected communities in mind. Extending back to the Groundwater Management Act in the 1980s, the legislation was chiefly designed by farmers and developers, while environmentalists and indigenous people were largely kept out of the conversation. With the state’s decades-long precedent of inaction and exclusion of critical groups from influencing new laws, it’s become clear that the people of Arizona must act to create change. As voters actually begin to feel the effects of climate change and water insecurity more intensely in the coming years, environmentalism will become a bigger issue for campaigns.

“Water security has been a rising issue, especially in 2022. I worked on political campaigns, and I felt that when I talked to voters, when I went door knocking for political candidates, a lot of times water came up as a very big issue,” Collings said. “As water starts to become more and more scarce, it’ll become more of an issue for voters. And hopefully, candidates will make it a more central focus of their campaigns.”