On Wednesday morning, I pulled up the New York Times “Politics” page and counted the number of times the names of declared or expected-to-declare presidential candidates appeared in the headlines. Jeb Bush led the way with six headlines, and Hillary Clinton came in at second with three. Marco Rubio, Chris Christie, Carly Fiorina, and even Donald Trump each merited one headline of their own.

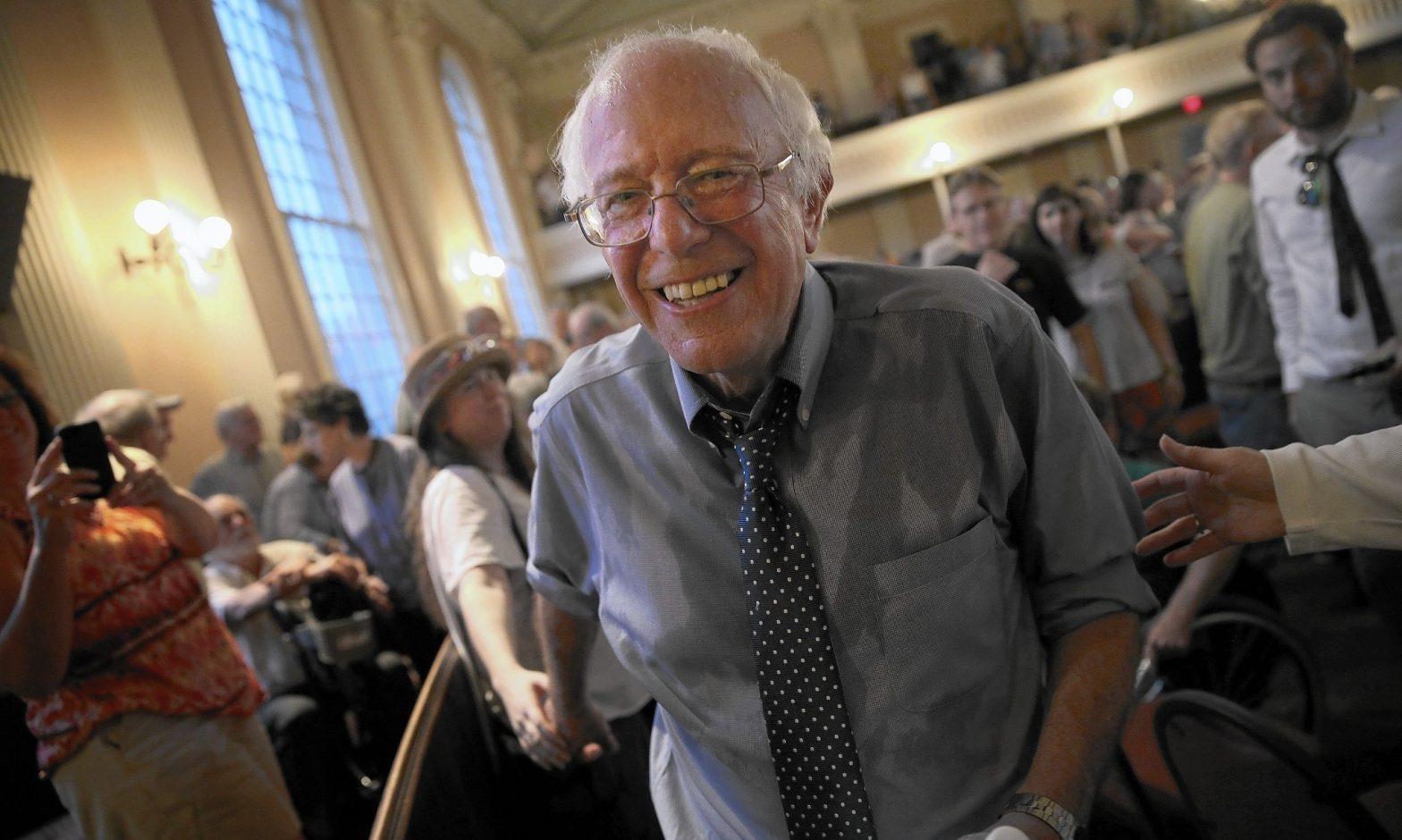

Notably missing from that list is the most serious challenger to Hillary Clinton in the Democratic primary: Bernie Sanders, who declared to a crowd of hundreds of people in New Hampshire last Saturday that he was going to win that state’s crucial primary. Or, to quote him directly: “We’re going to win the New Hampshire primary.”

Bernie’s right — if he pulls off a New Hampshire primary victory, it will be because of a “we” effort: the concentrated work of both the campaign and his staunch supporters in the state. There are more of those than you might think. Although an early May poll showed Sanders down by 28.5 points to Clinton, there has been an apparent groundswell of support for his campaign since then. In a series of events in New Hampshire last weekend, Sanders consistently drew hundreds of people to hear him speak, and the crowds were enthusiastic about his policies.

“People were excited to see him, and glad to see a progressive alternative to other candidates,” said Janice Kelble, a New Hampshire resident and Sanders supporter who attended a union-sponsored public event at which Sanders spoke to both members of labor unions and to attendees from the wider community. “Bernie Sanders is the one candidate that everyone involved in labor thinks respects and understands our issues.”

The crowds that Sanders drew in New Hampshire were consistently a mixture of younger voters and their older counterparts, evidence that Sanders may have more widespread appeal than many pundits have given him credit for. “He seemed confident that people are underestimating his ability to win the race,” said Kelble. “There’s a lot of people who aren’t taking him seriously, but he expressed confidence that he can do that, and people seemed really excited about it. He really has widespread appeal to a variety of people because he’s worried about things that affect a variety of people, but he actually puts his money where his mouth is. He walks the walk and talks the talk, and doesn’t just say stuff. He actually does things.”

To be sure, Sanders still has a lot of work to do to merely pull even with Clinton in New Hampshire polls, let alone beat her. And even if he were to win the New Hampshire primary, there is no indication yet as to how well he’d do in other vital states such as Iowa, where he’s spending the end of this week holding events. Recent numbers out of Wisconsin, however, seem to be promising for Sanders: in a straw poll of voters at the state Democratic Party’s convention, he finished only 8 points behind Clinton. For a candidate who doesn’t even call himself a Democrat, that’s surprising.

Or is it? Sanders’ approach to campaigning is much more personal than Clinton’s. At her campaign stops, she appears polished and visibly prepped, and her marketing team sends out email updates at least once a day, often twice, that read like the Hillary Clinton Gazette. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, and such a polished appearance is, regrettably, probably necessary for a female candidate who has already been subject to questions about how her gender and age will affect her presidency. But because Sanders has run counter to mainstream politics his entire career, his presidential campaign is able to run counter to usual campaign tactics. One of Sanders’ primary platform issues is his belief that big money and big business do not belong in the political system, a belief that he shares with the overwhelming majority of American voters. Although this stance puts his campaign at a significant financial disadvantage, it buoys his standing in the eyes of working and middle class families towards whom his message is directed. So, too, do his stances on increasing taxes for the wealthy, making access to healthcare a basic human right, and making public college tuition-free for students. If Sanders can turn out low-income and middle class voters in his favor, particularly in the primaries against Clinton, who is often perceived as out of touch, he could potentially beat her out in many key states, including New Hampshire. Could he beat her in enough states to clinch the Democratic nomination? Such an outcome is highly unlikely, to be honest, but possible all the same.

Sanders’ big problem, it seems, at least for now, is a lack of publicity. Americans don’t know who he is or what he stands for. In many cases, they hear the moniker “socialist” and immediately discredit him. Sanders has recently been attempting to boost his visibility and explain his policy positions through appearances on NBC’s Late Night with Seth Meyers and The Diane Rehm Show, which is distributed by NPR. He has a long way to go and will continue to struggle in the polls if major news organizations like the New York Times and CNN continue to give him less coverage than they give Clinton and the herd of Republican candidates. But if he is able to overcome this hurdle, pay attention to Bernie Sanders. His “political revolution” might be more likely than we think.