Before the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) came to power in 1949, Hollywood was the dominant player in the country’s film scene. According to some estimates, American films accounted for 75% of the film market during the 1930s and 1940s. However, with the arrival of Mao and the Communist Party, American films were purged from the country. As the party-controlled People’s Daily proclaimed in 1951, China has “swept out American movies that poison the Chinese people.”

Ironically, the single American film to screen in China between 1951 and 1981 was banned in the United States. The 1954 movie Salt of the Earth, which chronicled worker protests against discrimination in New Mexico, stoked concerns among U.S. officials that the movie promoted communist ideology; with members of the Hollywood Ten on its writing and production teams, the film became a casualty of the McCarthy era and the Hollywood Blacklist. In China, particularly in light of the US ban, the CCP heralded the film as “progressive” and permitted it to screen within the country.

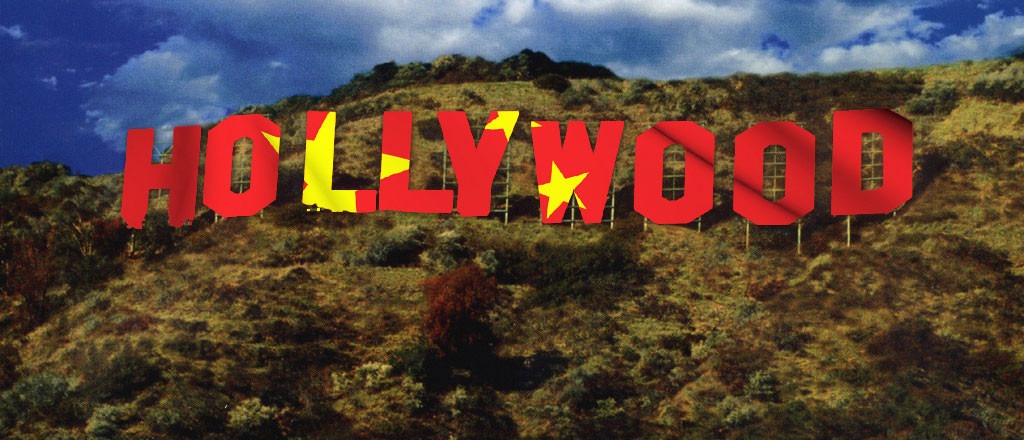

Overall, given the broad restrictions on Hollywood movies during the Mao period, China’s film market wallowed. Although Mao worked to nurture a domestic film industry that could fuel the CCPs propaganda, his efforts could not compare to Hollywood-level productions. Today, although China no longer bans foreign movies outright, it nonetheless wields enormous control over the content of Hollywood films. To some extent, despite the “opening up” of the modern era, China’s ability to harness cinema as a tool of propaganda has never been greater. Indeed, Hollywood increasingly bends to the wishes of the CCP, a trend that grants Chinese propagandists unprecedented global influence.

At the root of this development is the prodigious growth of China’s economy. While the country’s GDP stood at just $177 billion at the end of the Mao era, today it towers at over $9 trillion. This rapid growth has minted an expanding middle class, from which film distributors are eager to reap profits. In their eyes, given the saturation—and even decline—of cinemas in the US and Europe, China represents the next growth frontier. Chinese movie theaters are opening new screens at a pace of 27 per day, and, as measured by box office receipts, will soon overtake the US to become the largest film market in the world.

With billions of dollars on the line, international movie studios have started to bow to the demands of the Chinese state. Although Hollywood often prides itself on its autonomy and intellectual irreverence, this cultural streak has met its match in China. As Chris Fenton, President of the media company DMG Entertainment explained in an interview with The Politic, “If you’re distributing films in China, you have to respect the local preferences if your goal is to do business.” Put another way, the seductive appeal of the Chinese market often outweighs the importance of protecting creative freedom.

The Chinese government exerts its leverage over movie studios in numerous ways, all of which are outlined in its official “Film Management Regulations.” Adopted at the 50th executive meeting of the State Council on December 12th, 2001, the document articulates the rules and expectations of China’s film industry. Put simply, for a film to be made or screened in China, it must secure approval from China’s government censors: “Film scripts (outlines) not having been filed may not be filmed, films not having passed through examination may not be distributed, screened, imported or exported.” As the document continues, these regulations extend to “Sino-foreign coproduced films” and are enforced by the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television (SARFT).

China’s film censorship manifests itself in two key ways. First, all films that appear in China must undergo a story review by SARFT. Content that “endangers national security or damages the honor or benefits of the State” or material that “propagates obscenity, gambling, violence or instigates crimes” is banned. So too is content that “propagates evil cults or superstition” or material that “disturbs the public order or destroys the public stability.” In addition, for films that are shot in China, producers must submit a plot summary of “no less than one thousand characters” describing all story elements related to “foreign relations, ethnicities, religion, military affairs, public security, judiciary, famous historical persons and famous cultural persons.” Movies that explore these subjects are considered “special film subjects.”

Of course, these requirements still leave ample room for interpretation, which often leads to unexpected censorship. The 2013 film Captain Phillips, for instance, which chronicled the US Navy’s rescue of an American hostage from Somali pirates, had difficulty penetrating the Chinese market. While SARFT did not disclose its reason for blocking the film, one Sony executive surmised in a leaked emailed; “The big military machine of the US saving one US citizen. China would never do the same and in no way would want to promote this idea.”

Other films have made substantial edits to appease Chinese censors. The producers of Iron Man 3, for instance, decided to portray the film’s villain The Mandarin—depicted in the comics as an evil Chinese mastermind—with a Caucasian actor. The producers of World War Z changed the origin of the film’s fictional virus from China, as described in the book, to Russia. In addition, Marvel altered the origin of the character The Ancient One in Doctor Strange from Tibetan to Celtic. As Hollywood screenwriter Brian Price summarized in an interview with The Politic, a film’s palatability to China’s censors is “a constant consideration…There is simply too much money to be made.”

In addition to content restrictions, China’s Film Management Regulations also advance an affirmative vision of what movies should entail. Motion pictures should “stick close to reality, stick close to life and stick close to the masses” all while creating “excellent films integrating ideology, artistry and enjoyability.” Furthermore, films should “satisfy the people’s cultural life needs” and “promote socialist spiritual and material civilization.”

These ideas have a clear historical precedent in Mao Zedong’s teachings. In his 1942 “Talks at the Yan’an Conference on Literature and Art,” Mao articulated his belief that art should both support the cause of revolution and subordinate itself to the interests of the masses. In his words, art “can act as a powerful weapon in uniting and educating the people while attacking and annihilating the enemy.” In addition, Mao explained that for artists “the task of understanding people and getting to know them properly has the highest priority.” Unless artists became familiar with the people “they write about…and who read their work,” artists will become “estranged from them.”

These concepts were given a modern articulation in a 2014 speech by Chinese President Xi Jinping. At his “Talks at the Beijing Forum on Literature and Art”—a clear gesture to Mao’s Yan’an talks—Xi called for the creation of art that “can live up to this great nation and these great times.” Xi explained that art “must persist in the fundamental orientation of serving the people, and serving socialism” and that the best method for creating art is “taking root among the people and taking root in life.”

These core beliefs of Mao and Xi—that art should service politics and be inspired by the masses—bear striking resemblance to clauses in the Film Management Regulations, which call for motion pictures to “stick close to the masses” and “promote socialist spiritual and material civilization.” In other words, despite rapid changes in China’s economy and film industry, the CCP yearns to maintain Mao’s vision of art as a social and political force. And today, thanks to China’s enormous economic leverage, Hollywood has been enlisted in the cause.

Notably, SARFT’s content restrictions are not its only tool for influencing Western films. Hollywood distributors must also compete for one of only 34 spots allotted annually for foreign movies. This quota is overseen by the state-owned China Film Group—itself governed by SARFT—and is intended to prevent outside pictures from dominating China’s film industry. Given the strength of the Chinese market, distributors compete fiercely for the right to screen their films. Many producers, vying for limited slots, strive not only to meet SARFT’s core requirements, but also to exceed them. This means designing stories that deliberately cast China and its government in a positive light and that help, as the Film Management Regulations describe, to “promote socialist spiritual and material civilization.” The plot of The Martian (2015), for instance, was altered so that the Chinese Space Agency rescues NASA from an impending crisis. For the millions of viewers around the world, this rendition of the story surely helped burnish China’s image.

This competition for screening rights in China has also prompted Hollywood to hire more Chinese actors, a strategy that allows American studios to further ingratiate themselves with the CCP. However, beyond the political advantages, hiring Chinese actors also benefits Hollywood’s bottom line by enabling films to better resonate with Chinese viewers. In developing the sequel to the 2013 hit film Now You See Me, for instance, Lions Gate Entertainment decided to incorporate a Chinese character. This task fell to Jay Chou, the popular Taiwanese singer, whose presence in the film boosted its popularity. Although box office receipts in the US fell from $117 million to $65 million between the first and second films, the opposite occurred in China. Now You See Me 2 secured $97 million in the Middle Kingdom, a significant leap from the previous $23 million haul. On the coattails of this success, Lions Gate has greenlit the franchises’ third installment. It is also developing a spin off series—in partnership with China-based Leomus Pictures—designed specifically for the Chinese market.

Beyond the financial benefits of hiring diverse actors—and offering them diverse rolls—there are also cultural and diplomatic perks. Films with both Chinese and American actors help inspire cross-cultural collaboration and thinking. During the Cold War, by contrast, Russian actors appeared in Hollywood films almost exclusively as villains. Today, with Chinese and American actors saving the world side by side, Hollywood films serve to highlight our common humanity. Instead of nudging two countries to the brink of conflict, as almost happened during the Cold War, modern cinema may help to bring China and the US closer together.

Ultimately, despite these perks, China continues to leverage Hollywood to further its propaganda goals. Indeed, as the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission concluded in a 2015 report, “With an eye toward distribution in China, American filmmakers increasingly edit films in anticipation of Chinese censors’ many potential sensitivities.” This bending by foreign corporations to Chinese wishes—while not unique to the entertainment industry—is what NYU professor Aswath Damodaran dubs “the China trade-off.” Given China’s gargantuan consumer market, companies “accept rules and regulations [they] wouldn’t in other parts of the world.” Simply put, the financial appeal of China’s market is too seductive to ignore. As Disney’s CEO and Chairman Bob Iger recently proclaimed, China is the “greatest opportunity the company has had since Walt Disney himself bought land in Central Florida.” With stakes like these, Chinese censorship is a pill worth swallowing.

However, the global effect of China’s censorship regime should not be overlooked. For billions around the world, Hollywood remains a powerful influencer of opinion. Even slight tweaks in film scripts or stories can, over the long term, significantly impact public thought. If Hollywood films continue to skirt critical examination of China and its rise—and at the behest of the CCP—China may successfully execute one of the largest propaganda efforts in history. Unblemished portrayals of China, stamped with Hollywood’s legitimacy, will be an unquestionable influencer of public opinion.

Although China’s economy and film industry have changed substantially in the progression from the Mao era to now, the CCP’s commitment to utilizing art as a social and political force remains steadfast. Leveraging China’s immense economy, the Communist Party has successfully prodded Hollywood into bowing to the Middle Kingdom’s interests. Indeed, as the country’s 2001 Film Management Regulations outline, China has deployed its censorship agencies and a system of scarcity for film rights to advance its propaganda goals. The effect is that American studios not only avoid negative depictions of China, but also actively craft positive ones. In many ways, Hollywood has become a global spokesperson for the Chinese state.