Several highways intersect in the charming, albeit unremarkable manufacturing town of Cadillac, Michigan, which is nestled in the Manistee National Forest on the shores of two lakes and one river. The latitude of the northern Lower Peninsula provides a rare sweet spot for deciduous trees to coexist with the pines, and, in true Midwestern fashion, the people are perhaps too friendly. With all the bias of a lifelong resident, I can say that I have been to few places with more beauty and charm.

But my hometown faces many of the challenges plaguing rural Michigan as a whole: Wexford County Prosecutor Jason Elmore (R) cited early in 2018 that drug arrests are among the highest in the state per capita. Cadillac Area Public Schools—from which I graduated in 2018—reported a free or reduced lunch rate of 58 percent, which, according to the National Center for Education Statistics, defines the area as a mid-range poverty district. The relationship between education and poverty is apparent in Cadillac, where school facilities have failed to meet student needs for decades, and local property taxes and donations do not sufficiently supplement state per-pupil funding.

On May 15, 2018, the local Board of Education approved the first phase of construction on a 65.5 million-dollar bond to improve school facilities, many of which are cramped, outdated, and unsafe. In one high school chemistry classroom, students struggle in near-freezing indoor temperatures; in classrooms with leaky ceilings, overhead tiles commonly crumble and fall. Many of these spaces have needed repairs for years, even decades. The bond was a scaled-back version of a 2017 proposal that had been rejected by voters. Some of the upgrades in the 2018 bond had been proposed in a bond failed by voters in 1996, approximately ten years before current Cadillac seniors were of school age.

Lisa Kassuba, a fifth grade teacher at Mackinaw Trail Middle School, has worked in this school district for 28 years. “I feel like I was born to be a teacher,” Kassuba told me.

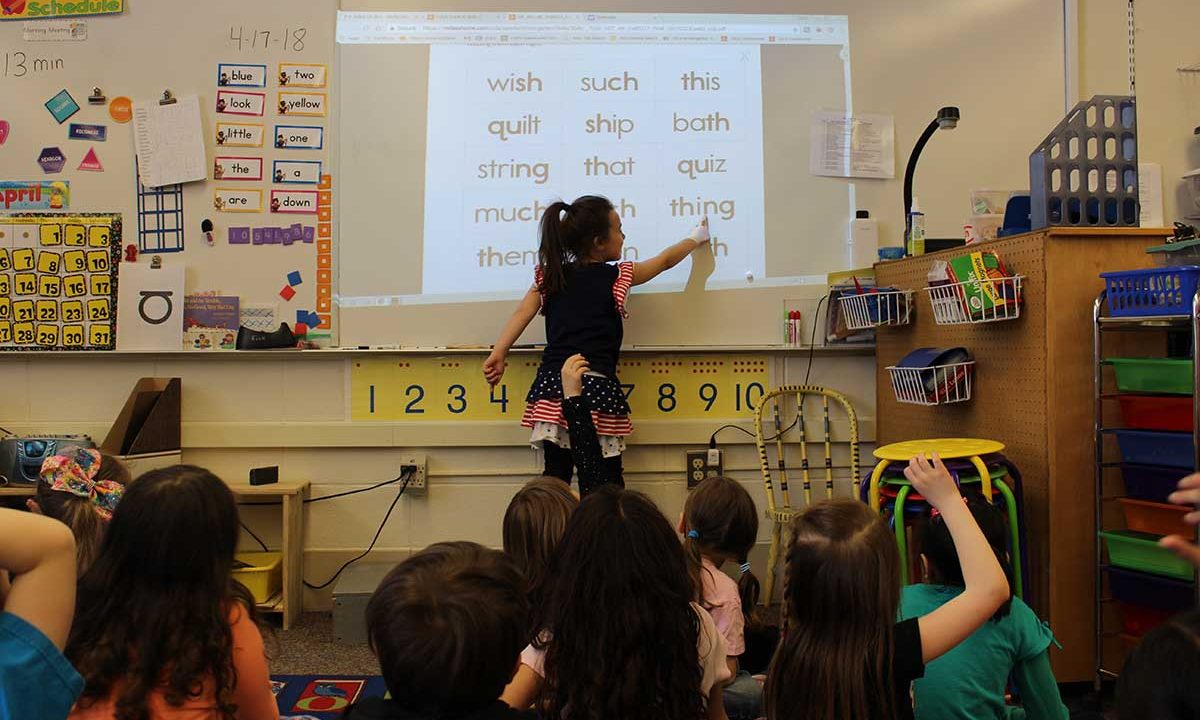

But Marsha McGuire, a kindergarten teacher at Franklin Elementary School, one of Cadillac’s four elementary schools, emphasized that although she finds her job rewarding, being a teacher also comes with a tremendous responsibility to personally fund supplies, professional development, and even students’ basic necessities. “In no other profession would we expect someone to put so much of their own money and resources into their job without being compensated [for it],” McGuire told me.

School budgets in Cadillac allot only small stipends of 100 to 200 dollars for classroom supplies, and these stipends rarely cover full expenses. McGuire said she has spent an “obscene” amount of her own funds supplying her classroom.

Sheila Bosman, a career educator who taught for Cadillac Area Public Schools before moving to teach kindergarten at a local private school, described experiences similar to McGuire’s. “As a kindergarten teacher, one finds that our meager annual classroom budget [at Cadillac’s public schools] just barely covers consumables such as crayons, markers, colored paper, glue, and paint,” she said. “I never had any extra money to replace broken items like puzzles and blocks.”

Teachers have learned to be cost-savvy, especially when required to fund classroom improvements themselves. “Teachers are hoarders, creative, frugal, recyclers, reusers, and bargain hunters,” Bosman said.

Teachers have not seen any significant raise in classroom stipends for decades. Meanwhile, inflation rates have averaged approximately three percent per year, and teacher pay in Michigan has eroded over the past two decades. Adjusted for inflation, Michigan teachers are paid 11.5 percent less than they were 20 years ago, and Michigan is one of 12 states that have cut school funding by more than seven percent per student over the past decade. Michigan allots Cadillac 7,500 dollars per pupil–the lowest amount the state allots to any district. Cadillac’s allocation is 26 percent lower than Michigan’s recommended minimum per-pupil spending of 9,590 dollars, which does not account for sharp spending increases recommended for at-risk and non-native English-speaking students.

Michigan’s per-pupil funding method was proposed in 1994 under the administration of John Engler (R), who was governor from 1993 to 2001 and is currently interim president of Michigan State University. The policy was originally intended to close the resource gap created under Michigan’s previous school funding structure, which funded schools solely through local property taxes. But rather than increasing education spending in poorer areas, Michigan implemented a tiered system that granted more resources to wealthy districts accustomed to higher education budgets. Despite the supposedly equal per-pupil allocations, inequality persisted.

Coupled with Michigan’s statewide fiscal challenges and declining property values, unequal education funding exacerbated the problems faced by poor school districts. Michigan also shifted funding to privately-run charters, favoring deregulatory practices and school choice. These policies, supported by advocates like current U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos, contributed to inequality in education resources and poor oversight of charter school performance. They funneled wealthy, white students out of public schools and created a de facto segregation policy.

The result? Although Michigan’s per-pupil spending was once near the median of its Midwestern counterparts’, a 2016 study from the National Education Policy Center ranked it at the bottom among Midwestern states. According to a 2016 report by the Education Trust-Midwest, Michigan’s public education has been rapidly decreasing in quality over the past decade. While this disproportionately hurts low-income students of color, the report notes, “Michigan is witnessing systemic decline across the K-12 spectrum.” Students are suffering—“white, black, brown, higher-income, low-income—it doesn’t matter who they are or where they live.”

Michigan has taken an increasingly deregulated approach to education, placing the well-being of its 1.5 million public school students in the hands of corporations by investing in for-profit charters at much higher rates than the rest of the nation. According to The New York Times, while for-profit charters account for just 16 percent of charter schools nationwide, they comprise 80 percent of charter schools in Michigan. Michigan now has the most for-profit charters in the country. And perhaps as a result, Michigan was ranked dead last in student proficiency improvements in a 2017 Brookings Institution analysis. Michigan lawmakers have allowed children to become vehicles for profit.

***

Despite struggling to stock their classrooms due to inadequate education funding, some Michigan teachers use their personal income to meet students’ basic needs. Bosman, the kindergarten teacher, recalled recycling her own children’s items, such as clothing and toys, and purchasing clothing for students.

“When your children outgrow something or no longer play with certain toys, you find yourself taking them to school,” she said. “I have even had to buy underwear, socks, boots, et cetera, to keep at school so there are extras when needed.” Kassuba, the fifth grade teacher at Mackinaw Trail, described pooling money with my mother, a school social worker, to fund a student’s haircut.

I was no stranger to this phenomenon. When my mother worked at Kenwood Elementary School in Cadillac, she regularly provided students with basic necessities, paying out of pocket and using donations. She became well-known for carrying personal hygiene products for students in her purse, her car, and her office. When I was in elementary school, my mother sought donations for kids’ snow pants and boots and, once, a new skateboard. She has anonymously funded thousands of dollars worth of Christmas gifts for Cadillac families.

Bosman ruminated: “Why do we spend our own money? One, we don’t want any child to go without. Two, you can’t ask for school supplies in a public school. You can ask for donations, but you aren’t likely to get much. Three, you want the education setting to be safe, happy, and engaging.”

A 2015 federal Department of Education survey found that nationwide, 94 percent of teachers had spent their own earnings on school supplies, and seven percent had spent over 1,000 dollars annually on school supplies. According to McGuire, teachers have always spent personal funds on classroom supplies, but it is “becoming more apparent because social media and the voices of teachers has helped tell the stories of what is really happening in the lives of teachers and their classrooms.”

McGuire emphasized that effective teaching requires investment in creative teaching strategies, which can often be expensive. McGuire said, “If you want to have a hands-on, engaging curriculum for science—or even ELA or math—you need materials that your students can touch, manipulate, and explore. These items [have to] come with a new classroom. As a teacher, you are on your own to figure out how to acquire them.”

Adding to teachers’ expenses, quality education in the digital age requires access to technology. Psychological research cited by Edutopia, a popular education blog, portrays learning as a social and interactive process, one that cannot be reduced to bubble sheets and flash cards. Cadillac teachers favor methods like peer revision and small-group discussion, which aim to foster personal growth and a more detailed understanding of concepts. Many of these methods make use of technology like Google Suite and online forums.

My high school English class required us to submit weekly blog posts; in math, we used grant-funded Smart Boards and interactive videos; and for chemistry, teachers and students scrounged up money for sensors and graphing calculators while relying on excruciatingly slow computers for our labs. Even Kahoot, the popular review game, requires one technological device per student. McGuire explains: “The fact is, teaching in paper and pencil is just not a reality, and it’s not [the] best teaching practice.”

According to Benjamin Herold, a staff writer who covers education technology for Education Week, American public schools now house at least one computer for every five students. The same blog stated that the 2015-2016 school year was the first in which standardized tests for elementary- and middle-school students were administered more frequently online than with pencils and paper.

However, lack of access to technology remains an issue, especially in rural areas. Cadillac’s 2018 bond aims to provide each high school student access to one device for classroom and home usage, but this goal is unlikely to be met for several years. Cadillac elected not to add one-to-one technology for K-8 level students due to research indicating potential harms of some screen technology for young children. Even so, the bond has no provision to grant elementary and middle schools important resources like computer labs or laptop carts.

In order to fund technology-focused opportunities for students, many teachers have turned to educational grants and professional connections. Two of my high school teachers kept grant-funded, mismatched sets of Google Chromebooks and iPads in their classrooms, but there still were not enough devices to meet student demand.

Teachers are also using technology to raise money for other needs. McGuire described using online crowdsourcing and fundraising platforms like Teachers Pay Teachers to share resources with other educators.

Kassuba recalled discovering how to attach an Amazon wish list to the Remind app. “I did it, and within an hour, parents had donated 50 dollars of the specialty paper I wanted for the kids to do a project. It was amazing because I couldn’t go out and buy 50 dollars worth of paper. I could do it once, maybe, but I couldn’t keep doing that kind of thing.”

Social media allows teachers to engage with their professional networks, too. On Twitter, they share inspiration, ideas, professional development opportunities, and raise funds.

But fundraising on Twitter is haphazard and, ultimately, insufficient. The Department of Education’s 2015 study also found that on average, teachers spend nearly 500 dollars a year on classroom spending. This amount does not account for the items teachers bring into their classrooms from home—hand-me-downs from their own children, for instance—or buy with donations. Still, it is double the 250 dollars in annual federal tax deductions that teachers can receive for personal spending in their classrooms.

Kassuba told me that classroom purchases occur throughout the year. “Every week when I buy groceries, there’s something in my cart for my classroom. And I just do it because it’s what I need to do my job. I don’t really think about it—it’s not always a lot at one time—but if I need it, I buy it,” Kassuba explained.

“I even found myself rationalizing my spending by telling myself it was a gift to the students,” Bosman reflected.

Having spent 14 years in the Cadillac Area Public School system, I was frequently caught between an instinct to criticize rural schools’ lack of resources and a desire to laud their outstanding educators, who sacrifice their personal comforts to help kids who might otherwise go without. Cadillac teachers refuse to allow their students to become casualties of state budget battles.

This students-first mindset defined my experience as a student in Cadillac. My teachers saw financial investment in their classrooms as investments in us—their students.

My classmates have told me stories of teachers who transformed their experiences in K-12 education—teachers who invested in them. My chemistry teacher, for example, would stay several hours after the end of the school day to work with students.

“I know that many teachers feel that if we continue to supply classrooms using our own resources, things will never change,” McGuire explained to me. “But I’m not that teacher that can just turn the other way and ignore the needs of my students.”

By the end of a recent conversation with fellow Cadillac alumni about the people who made a difference in our high school lives, nearly every teacher was mentioned.