Look past the strange fruit swinging in the Southern breeze and see the crowd smiling and cheering, forever immortalized by the flash of the camera. The doctors, lawyers, accountants, secretaries. The young and the old, the rich, and the poor. And some of them were devout Christians who went to church on Sunday after the lynchings.

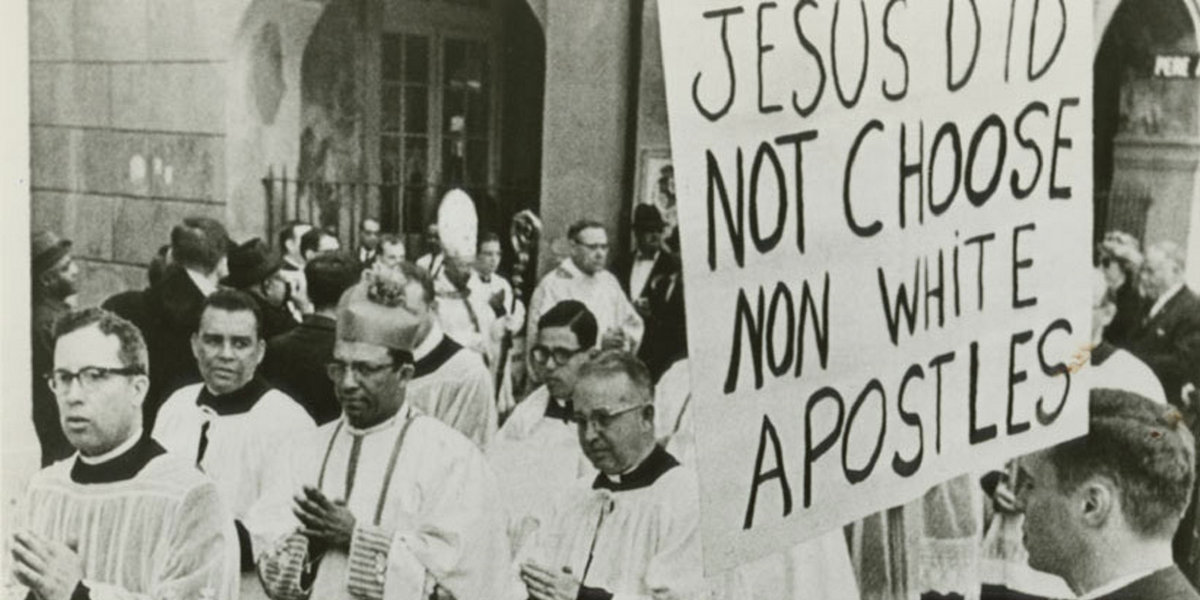

Christian ideals are often weaponized to support the architecture of race in America, and hate groups have often misappropriated its most potent symbols—especially the cross. As Klan leader Barry Black said in an interview with the Roanoke Times in 1999, “We don’t light [the cross] to desecrate it. We light it to show that Christ is still alive.” Biblical allusions fill the pages of the Kloran, the seminal text of the hate group that articulates the Klan’s beliefs and rituals. With white robes and hoods representing cleanliness and purity, the symbolism of the Bible acts as a means to the end of hatred. The primary symbol, the “Mystic Symbol of a Klansman” (MIOAK) is a white cross with a red teardrop.

As a black Christian, the notion of Christ living in one of the most potent symbols of bigotry and anti-black racism appalls me. But the hand-in-glove relationship between white Christian ideology and white supremacy cannot, and should not, be ignored. Like metastatic cancer, racism invades every facet of American life and every institution in our society. It is not a defect that can be effaced by minimal change. It is the rule, not the exception. Unfortunately, churches in the United States are not free of prejudice. Research conducted by Clemson University sociologist Andrew Whitehead demonstrated that white Protestants who believe most strongly that Christianity should hold a privileged place in America’s public square are more likely than others to agree with statements such as “Police officers shoot blacks more often because they are more violent than whites.”

Histories of racism demand a reckoning. They call on us as a Christian community to seriously grapple with the harm some of our members have done. With hypocrisy. Because the honest, ugly truth is that some of us act in ways that have nothing to do with Christ.

“The good Lord set up the customs and practices of segregation, “ said Dr. John Buchanan, a prominent pastor in Birmingham, Alabama in 1957. White churches were not only complicit in the regime of white supremacy in postbellum America; they were part and parcel of its apparatus. In the pages of the Bible, white religious institutions found words encouraging compassion, love for others, and selflessness and weaponized them, grounding theology in the strictures of white superiority. This was the crucible in which the African Methodist Episcopal church was forged in 1787. With knees bent and hands clasped, Richard Allen and Absalom Jones dared to pray in the whites-only section of St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia. And they were violently dragged out by white congregants.

Yet from that crucible emerged a tradition of social justice in the black church that undermined the roots of the racial caste system in America and articulated prophetic moral visions of a better country and world. Churches were vital to the success of the civil rights movement and served as meeting places where leaders like Martin Luther King Jr., Montgomery minister Ralph Abernathy, and New Orleans Congregationalist minister Andrew Young strategized and planned.

Faced with the slurs, systemic oppression, loss of opportunities, and white terrorism, African American people sought the haven of the black church. But even within its walls, they were unsafe then. And they are unsafe now. So when the shrapnel of a bomb made by the KKK tore through the 16th Street Baptist Church and killed four little black girls in Alabama on September 15, 1963, it stung. And when a white gunman killed nine congregants at the Emanuel African Episcopal Church in South Carolina on June 17, 2015, it stung.

But despite the best efforts of religious civil rights leaders, white supremacy remains undefeated, manifesting itself in insidious ways. We need to talk about the myriad of ways you can make a space uncomfortable for people of color without a “Whites Only” sign. To this very day, 86 percent of American churches lack significant diversity. Not only do churches lack meaningful racial diversity, but they are also 10 times more segregated than the neighborhoods they are located in and 20 times more segregated than nearby public schools. Despite the good intentions of some white pastors, there are institutional realities that point to the fact that, to some, the church is a place of refuge from non-white people. 11 a.m. remains the most segregated hour in America.

Anti-blackness in white churches knows no bounds. It manifests when white church leaders call young black children the n-word. It manifests when Vacation Bible School teachers ask students to pretend to be Israeli slaves, while teachers pretend to be slave masters. We don’t gravitate towards predominantly-black churches to “self-segregate:” we do it to escape white supremacy in houses of worship.

Jesus embraced all people with open arms, regardless of their societal status—the poor, the downtrodden, the marginalized. If white Christians are whom they claim to be, they need to own their role in perpetuating white supremacy. If they truly love their neighbors as themselves, there should be no room for racism, discrimination, and hate.

When you respond with silence—or worse, “All Lives Matter”—to calls for the end of police brutality and systemic racism, it tells me all I need to know. It tells me that you don’t love us at all. It tells me that your emotional safety takes precedence over our physiological needs to live. Eric Garner and George Floyd couldn’t breathe. None of us can. Some of you, like Derek Chauvin, have your knees on our necks, depriving us of humanity and respect with words and actions steeped in the bitter poison of racism and hatred that threatens to consume us all. Like Thomas Lane, J. Alexander Kueng, and Tou Thao, some of you stand watch. But your neutrality doesn’t cloak your complicity very well.

But I am optimistic because that is the only choice we have. And if there’s one thing I know for sure, it’s that despite our darkest, most hateful impulses, people have good in them. I know that because of people like Episcopal seminary student Jonathan Daniels, who vocally advocated for civil rights and was killed because of it in 1965. And it gives me hope to see clergymen of every color joining hands and protesting injustice in the streets of Minneapolis and all over the country. Our faith empowers us to fight for justice, and so many honor that call.

The call to “love our neighbors as ourselves” is not rooted in sentimentality or mush or comfort. It is deeply rooted in a sense of justice and empathy towards our fellow man. If your love only extends to the blonde-haired and blue-eyed and pale-skinned, then it isn’t loving. Beyond anti-black prejudices, we need to think deeper about how to love our neighbors. So we need to love our atheist neighbors. Our Muslim neighbors. Our Jewish neighbors. Our incarcerated neighbors. Our neurodivergent neighbors. To only seek the comfort of homogeneity is to ignore the call placed before us and reject the radical kindness that Jesus exemplifies.

Before Jesus explained the parable of the Good Samaritan, a lawyer posed the question, “And who is my neighbor?” We all need to ask this question of ourselves and of each other. Together, we must create a more expansive definition of neighbor that reaches beyond class and race and nationality and ethnicity and skin color and geography, while acknowledging the specificity of our conditions and the historical and social contexts that shape us. Failing to do so will continue to add gasoline to fire of racial prejudice and white hostility.