Martín Nova is a Colombian executive and, according to his country’s Dinero Magazine, one of the 50 most influential people under 40 in the national business scene. He is also deeply engaged in the country’s cultural scene. He was the executive producer of the nature documentary Colombia Magia Salvaje, the highest grossing film ever produced in the country, and wrote Conversaciones con el fantasma, an account of the past 50 years of Colombian art history.

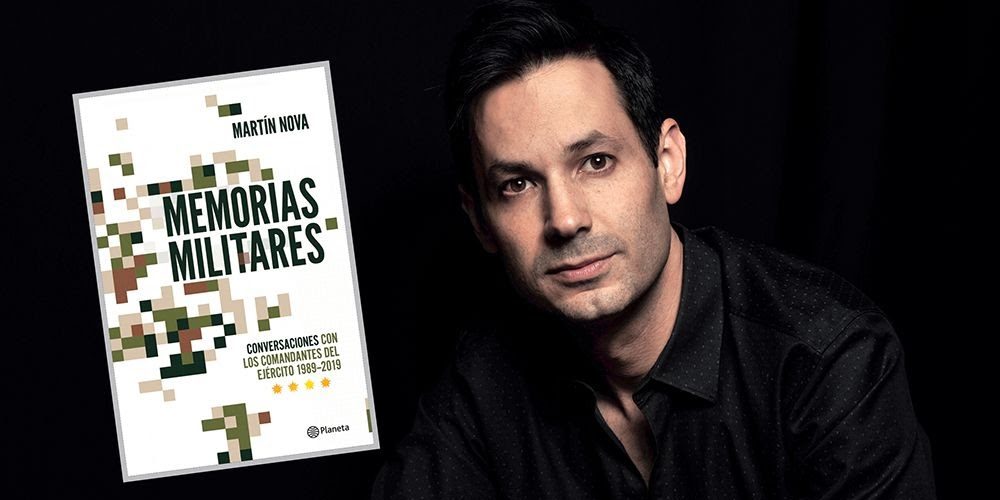

The Politic reached out to him to discuss his most recent book, Memorias Militares, rooted in his conversations with Colombia’s army generals from 1989 to 2019 about the armed conflict that dominated the country’s history for 30 years. The conversation includes insights from these generals, the lessons their experiences can provide in other spheres of life, and the overall importance of listening and writing, both in one’s personal life and to enrich our historical records.

***

The Politic: Considering your position in the world of business, what drove you to get involved in the process of writing?

Nova: I think that’s a very good place to start. I’ve always been a very restless person with a very curious mind. I think that a person must have different interests and hobbies, and especially an executive must always have interests apart from those of business, because everything is complementary. What I try to do with these processes is to learn and to deepen my own knowledge. For example, when we talk about art, which is very interesting to me, art is an ideal complement for any person because it awakens their creative, innovative, disruptive, empathetic side. It also involves marketing, because at the end of the day marketing, which is one of my great passions, requires considering what the other person is thinking and feeling. Now, with my book about the military, there’s a similar motivation: learning. Ultimately, a successful business depends on a good security environment in the country where it operates, so understanding how that’s achieved has also drawn my attention.

Secondly, I’d also say it’s an interest that comes from my household. My parents and grandparents have always been people connected to the world of culture, to the world of letters, and the world of art. My grandfather was one of the precursors of the contemporary art scene in Colombia, creating the “Bienales de Coltejer” events in the ‘60s and ‘70s. I would say that it’s inescapable for that reason—I can’t escape the world of art. I spend a lot of time on it, and I feel a great passion for it. And at the end of the day, writing is just that—it’s a manifestation of art and culture that is always present in my life. And so when there’s a topic that interests me, that captivates me, that’s how I explore it. Nowadays, I’m also working on another couple of projects, both related in important ways to the one we’ll be discussing today.

It is interesting that you describe writing as a form of art and creative expression, because, at first glance, Memorias Militares seems like a mostly investigative work—fundamentally a collection of interviews. How would you describe the relationship between investigative and creative writing? Do you think this may be a dichotomy worth questioning?

Yes, and I think that the paradigm I’m proposing with these books will be increasingly understood. My intention was never to start writing—it was something that kind of won me over. One day, I carried out my first interview, on art, and that was the beginning. I interviewed Gloria Zea, a very important art museum director in Colombia and the first wife of Fernando Botero, the famous painter who was friends with my grandfather. That was the first one, and so the project got started and I understood the value of these kinds of conversations. And I think it’s very interesting that you use the term “collection of interviews,” it’s a term that someone [else] also used to describe my book on art—“what an interesting idea, collecting interviews.” But I think it’s not exactly accurate, in fact I see what I’m doing as very different from a collection. There’s a person who really inspires me on this whole subject of interviews, his name is Hans Ulrich Obrist, one of the greatest art curators in the world, and he sets up a very interesting model of open conversation, rather than a unidirectional interview. In any case, I don’t see myself as a collector of interviews—what I really want to do is to tell stories. And so what I found is that the tool of the interview is very useful. When you begin a real dialogue with someone, you find that everyone has something to tell, a story to share, but we need to listen.

What I did with the art book, on some level, was to tell the story of my grandfather through people who knew him, and then that evolved, and it became a long story about art history in Colombia from personal experiences. And that happens also with Memorias Militares. If you pick up the book, what I try to do is tell the story of the Colombian armed conflict over the course of the past 30 to 50 years through the eyes of the commanders of the Colombian army, who were real witnesses because they lived it. I interviewed almost all of the ones alive at the time. What you’ll find [in the book] is a common story where each general passed the torch to the next, and you will read that view of our history. The questions are framed in such a way that I try to tell a story by letting them speak. Every story is independent of course, but at the end of the day, they tell a common story. All of this is to say that the interviews are not ends in themselves, but narrative tools to tell a story. I also don’t want to turn the interview into the chronicle. In this book, I wanted my effort to be more like that of a curator or an investigator than an expositor of my own perceptions of our history. I try to be very clear in this—I am a vehicle for their story.

Interesting. So, why did you choose to cover the perspectives of generals in particular for your second book? What drew your attention to that subject?

Well, I would tell you that this book has a very clear origin. It’s written in the book—during my whole life, I’ve had a certain degree of closeness with the Colombian military world. I took a course in 2017 called the Integral Course for National Defense (CIDENAL), and it’s designed to give civilians the opportunity to contribute to, and learn from, military thoughts and strategy. A lot of politicians take that course, and in that course, there are lectures and conferences. I clearly recall one delivered by General Juan Pablo Rodríguez Barragán, who is among the interviewed in the book. He led the Colombian armed forces during most of the years of the recent peace process with FARC, so he had to deal with that whole difficult period and its challenges during the Santos administration. And he gave us a very interesting quote: “The one who wins the war is the one who writes the historical memory, and the FARC are 15 years ahead of us in writing the historical memory,” despite the fact that the FARC were clearly defeated by the military and obliged to a negotiation. So, from that point he was already aware of this danger, and the topic of historical memory and history more broadly has always drawn my attention. When I heard that quote, that was the seed for this project. I started to contact every general alive, I sat down with them; of the 16 who were then alive, I sat with 11. Two have died since, so I was privileged to speak to them on time, and that’s the book: the personal memories of the generals. There is clearly a vision, a set of memories from Colombian history, narrated by its protagonists.

Now, when you talk about the issue of historical memory and the unfortunate advantage of the FARC in that regard, what would you say is the greatest mistake in common discourse surrounding the Colombian conflict, whether domestically or internationally?

As I said before, I think before I answer it’s worth mentioning that my intention here is not to give my own point of view, but to be a vehicle for the transmission of a vision and a series of thoughts beyond my own. And I was very careful in that regard—in many ways, it was not easy, it was the defining challenge of writing this book. And I insist a lot on that word—“vehicle”—I am a vehicle.

Now, with regards to your question, I could give you a myriad of different answers, but what really draws my attention in particular is that, when you look at the official website of the Nobel Prizes, and you see their justification for the Nobel Peace Prize granted to former president Juan Manuel Santos; it says that he made great efforts to end a “civil war” in Colombia. So, for example, that’s very interesting to me, because in Colombia there is no such civil war, nor has there been a civil war for the past century. There should be an effort to change that international perception, because it’s very difficult when historical memory is built on such digressions. And so really, the book is about that: it’s about really asking what exactly Colombia has been through.

When you talk about Colombia not having faced a civil war recently, can you clarify for our readers what a civil war is and why conflicts like the War of a Thousand Days in Colombia and the American Civil War would be included while the Colombian experience of the past 40 years would not?

I will insist again that I am neither a historian nor a purveyor of my own opinions, but a vehicle. I just try to ask questions out of legitimate curiosity and seek out the answer. I asked the same question you asked me to the generals in the book—what do you call what Colombia went through, what is a civil war?—and you will find all of those theoretical answers there. We’ve had all sorts of generals, and a lot of them are supremely studious and strategic. For example, there’s General Ospina, who really gives a master class during his interview, and he tells us what a civil war is, because it does have a definition. The generals I interviewed variously described the Colombian armed conflict as either an insurgency or an irregular armed conflict.

Right, that makes sense. Now, returning to General Ospina, having watched the book launch where he participated alongside you, I recall him emphasizing the difference between the strategic and the tactical mentality in military affairs. Could you explain this distinction as he understands it for our readers and, returning to the idea of interdisciplinarity, do you think that this is a useful paradigm in other spheres of society, such as in your life as a businessman?

Of course, I think that’s a good question! Now, this book can be understood in many different ways. You can see it as a book about Colombian history, about war history, some may see it as a work of journalism because it has a lot of “chivas,” or fresh details, although that wasn’t what I was seeking. I was much more interested in the human side of the general in his solitude. You could define that it’s a book about leadership, but it’s also a book about strategy, because clearly, beyond your question, which I’ll get to in a moment, one does see that in the military world everything that happens is derived from a broader strategy, which then extends to the specific tactic or operation. And that’s discussed very deeply, especially in terms of how a successful general must transcend the tactical mindset and adopt a strategic mindset, something not all military officers can achieve. A general needs that. And the same thing happens in the business world, because at the end of the day, it’s also a world of leadership and strategy. A high-ranking executive without a strategy, without leadership, and without teamwork, cannot do anything. He can’t do anything. At the end, we are all nothing more than the team we lead and how we lead it, as well as the strategy we conceive of, with all of the sacrifices we need to make to deliver it. I do think it’s a very good question, and I have never had it asked to me before nor did I consider it, but it goes to show how the book can be read in so many different ways, including as a lesson in strategy and leadership.

Of course. Well, I ask this in part because of the general tendency in today’s corporate world where many people go to their workplaces, do what they’re told to do, but ultimately don’t see the larger purpose of what they’re doing. They feel that their jobs are useless, and this makes them demoralized. Do you think maybe there’s a greater need today for business leaders to make sure that their employees understand the strategy behind what they’re doing?

I think that’s indispensable. It’s absolutely necessary. You bring up another interesting word—“purpose”—related to some of the generational changes we’re seeing in how work is perceived. At the end of the day, the new generations leave college and they aren’t thinking, as our parents did, that they want to join a company, serve it their whole lives, and then head off to a peaceful retirement. Now, the new generations are thinking instead about how they can change the world. They don’t work only for a paycheck, but also for a chance to change the world and serve a broader purpose. That’s why it’s so important for all companies to make their purpose a motivating force, relating again to the issue of leadership we discussed earlier.

You said that the most interesting aspect of the book to you was the human side of the generals. What surprised you the most in that regard?

Yes, what I have been trying to do precisely is to capture the human side, even in a book dealing with such a loaded political subject nowadays. Colombia is at an important juncture in its history, with a relatively recent peace process, the difficulties of the pandemic, and increased political polarization. And maybe that juncture limits the way in which many people will view this book, without considering its broader significance. This book is written as a historical document, intended to serve as a reference point for one of the harshest periods Colombia has faced since its independence. It will remain interesting for the next 30, 50, or even 100 years for that reason. But that isn’t so evident now because its immediate relevance clouds its longer-term significance, making people think it’s only a journalistic book rather than a historically significant one. That’s not what the book is, and I’ve never wanted it to stay at that. Now, when we talk about the human side, my belief has been that we need to learn from the wealth of every person’s experiences. I was especially interested, in this specific case, that the generals, while typically perceived as distant, authoritative figures, came off in the way I heard them and observed them as being much more like the average person than one might expect. I’m inspired here by another quote—the idea that “armies look like their countries,” because they’re so big and draw people in from a range of different regions. These are people with solid family backgrounds, albeit from a range of very different families, despite the difficulties of family life when the father needs to be away in dangerous regions. Above all, the vocation of the military man to serve his country is constant. Each of these generals, without exception, said that they would rejoin the armed forces if they were born again. All of them. Of course, it was the life that they led, and the life where they succeeded, but they also have such a strong sense of pride in their institution.

To conclude, what would you say is the most important lesson you’ve learned throughout the process of writing Memorias Militares?

On a personal level?

Yes.

Or on a historical level?

I had the former in mind, but if you would like to answer both, that would be perfect.

I would ratify what I said a while ago, perhaps, and that’s the importance of listening to others, of hearing points of view. No one has the only truth. And I would ratify that to me, that’s what a lesson is—it’s about the value of the word, the value of stories, and the value of people. And it’s something that I will continue to work on, because both in this last book and in my previous one, I’ve found that it’s the only way in which we can build a much more valuable historical record. On a historical level I have no doubt that this book is a key material for any Colombian to read, especially the new generations, the ones that didn’t live those tough years in the past decades.