Why the Rust Belt is not working

The Rust Belt is coming to grips with the changing world of work. Automation, international competition, and industry consolidation eat away at steel and coal production. As manufacturing jobs lose ground to white-collar or low-wage service work, a new work ethic is developing and threatening to replace the work culture that sustained a blue-collar middle class. Economic security now demands a college education, but many resist what seems foreign to blue-collar values based on manual labor. From joining gangs to opting out of work entirely, resistance to the cultural transformation of the post-industrial economy takes on many forms, most of which hinder the transmission of a work ethic from parent to child. Now, people in the Rust Belt are not just worried about the future of work; they are uncertain if there will even be one.

*****

In the Rust Belt, the value of hard work has grounded identity and community for generations. Steel jobs in the 19th century built the Rust Belt in all its families, communities, towns, and cities. For a few places, they still serve that role. “We are the community,” said Pete Trinidad, the President of Local 6787 of United Steel Workers in Chesterton, Indiana. Chesterton, like much of northwest Indiana, has flourished thanks to the steel industry. “A job means everything,” he said. It means feeding, clothing, and raising a middle-class family, retiring with dignity, and leading a decent life. Pete worked to win the union members’ benefits: healthcare, pension, vacation, overtime and holiday pay, and a family wage above $100,000 in annual income. And these benefits don’t require a bachelor’s degree – thanks to the union, the plant will train you on-site. Pete is proud to say his mill has the best steelworkers in the world.

Before unions gave industry workers these material benefits, steel communities produced an identity based around men laboring for lengthy shifts in smoke and heat to provide for their families and contribute their part to national prosperity. Founded in 1800, Johnstown, Pennsylvania, quickly became a steel town and home to Polish, Lithuanian, Italian, and other eastern and southern European immigrants who found opportunity in the steel mills. Rebuilding after the flood and fire of 1889 demonstrated the strength of the steel community. The mills meant more than a job. They represented an ethic, a way of life. This spirit rooted generations of steelers in the valley, resisting its natural proclivity to flood and wash away civilization.

Johnstown’s resilience originated in its work ethic, and the steeler work ethic sprang from the pride of providing for one’s family and contributing to the community. Eight-hour shifts ran from 7 AM-3 PM, 3 PM-11 PM, and 11 PM-7 AM. If a worker didn’t show up for his shift, someone else would be forced to cover it, inculcating a strong sense of personal responsibility to show up and work hard. At the same time, workers and their families could rely on one another if in a bind because mill work structured the town – the community pitched in to make sure the kids didn’t go hungry during strikes. Sharing the same work-life meant workers would toil away side by side, blow off steam at the same dive bar, and go home to sleep – then repeat it all the next day. The tight-knit community ethic of families supporting one another forged a certain dignity for workers that ensured the furnaces burned hot, day and night – nothing else could.

Today, only remnants of the steel industry remain. The scrap metal factory on the outskirts of the town feeds on the former life of the steel mills, squeezing out what it can. But the blue-collar work ethic that built Johnstown hangs on for survival.

Samuel Esbasito sat on his retirement pension and his porch, watching the annual amateur baseball game begin in Johnstown. Sam’s father came from Genoa, Italy, and worked in the mills in the 1960s to feed a family of 15 children. Immigrants built enclaves around the mills. Through his scraggly grey beard, Sam mumbled, “Working hard won’t help you anymore.” He meant that industrial work can’t help families and communities survive since the mills shut down. “Everything is overseas. You get something made, it’s overseas.”

Though Sam recognized industrial work is hard to come by, he attributed the prevalence of welfare dependence to cultural decline rather than the loss of economic opportunity. “People giving [non-working people] everything made them that way,” he grumbled. “People who don’t wanna do nothing, who don’t wanna work, don’t bring ‘em to Johnstown.”

Holding just any job doesn’t count for the old guard like Sam who grew up when industrial work was plentiful. “Them half-way house people, they work at McDonald’s over there to pay their bills because they are afraid to go out and get a job,” Sam asserted. “They don’t want a job.”

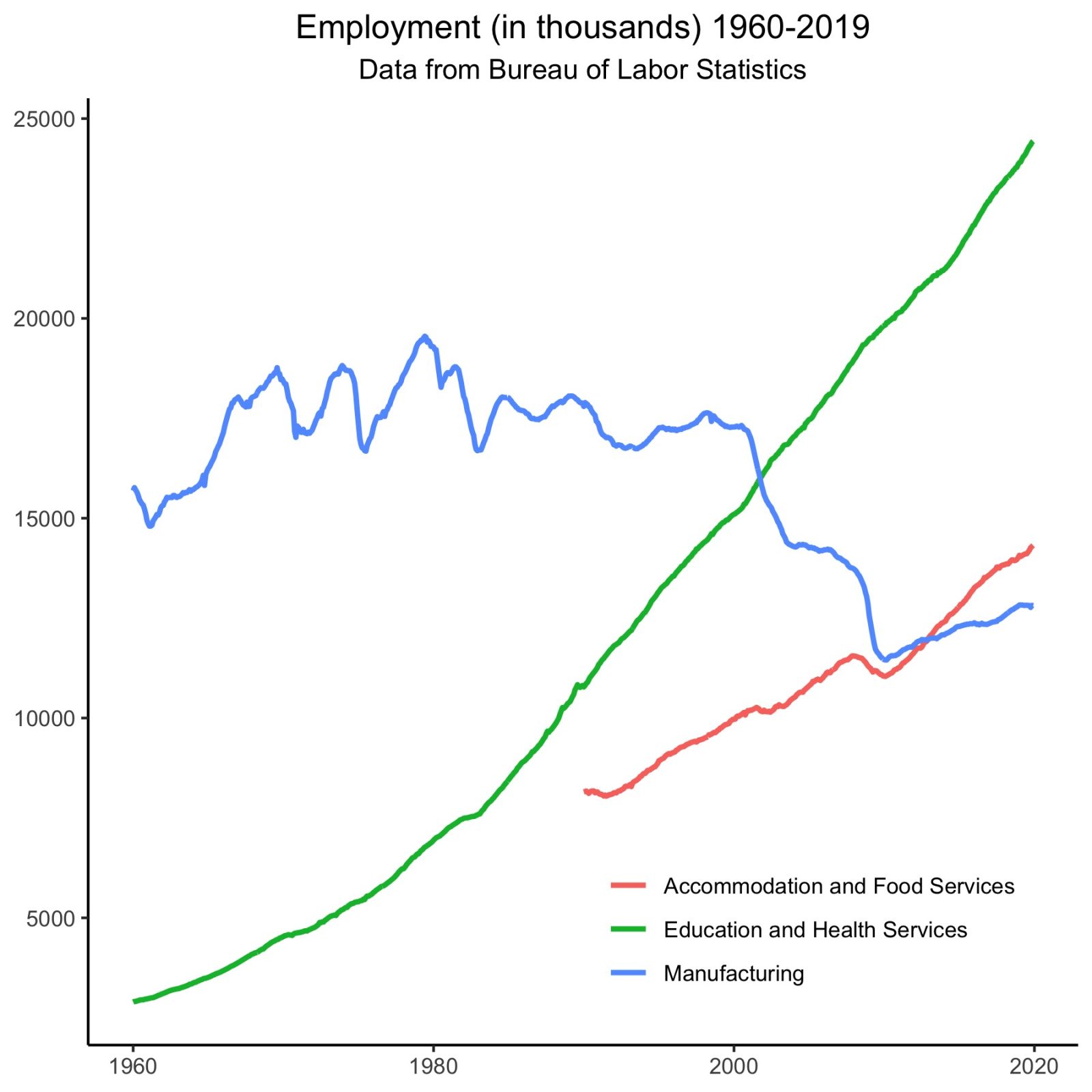

According to Jennifer Klein, a history professor at Yale, the value of work is tied to definitions like “breadwinner” and “masculinity.” In a place like Johnstown, service jobs fall outside of a conception of hard work that had once meant working in the mills to provide for one’s family. This is a problem. Low-wage service and care jobs have been outpacing manufacturing jobs for several decades, a gap that will only continue to widen.

“If the mills were to leave, just look at what happened in Gary,” said Pete Trinidad, who hails from nearby Chesterton.

Gary, Indiana, was once a true steel town — its plant manager was the mayor. Today, U.S. Steel owns the last mill in the city. As of 2015 it employed only 5,000 workers of the 30,000 it had in 1970. They’re no longer unionized. Thirty percent of Gary lives in poverty. The once-commercial main street of Broadway now largely consists of gas stations, dollar stores, and boarded-up buildings. Newly painted residences sit next to burned-down homes and spontaneous treehouses. Only 20 minutes away from the Cleveland Cliffs mill in Chesterton, Gary is a warning for steelworkers.

When a mill closes and workers lose their jobs, it can be devastating. The skills workers develop in the mill over the course of their lives are hardly transferable to other jobs. “It’s very tough for someone in their 50s used to working in the steel mill environment to go out and work for Google,” Pete said.

As industrial mills and factories close, so do their unions, diminishing middle and working-class earnings as non-college-educated workers have to take non-unionized, low-wage service jobs. It is no wonder that since the onset of deindustrialization, men 25-54 have steadily dropped out of the labor force, declining from 97.1 percent in 1960 to 88 percent in 2021.

While the U.S. has seen mortality rates halve over the 20th century, the increased deaths due to alcoholism, suicide, and opioid abuse among non-college-educated prime-age white men have been so dramatic as to increase the overall mortality rate for the group, including those with bachelor’s degrees. The causes of these deaths are debated, but they surely include the disappearance of industrial jobs.

A 44-year-old bartender and former union representative at a paper mill, Danny witnessed the heroin epidemic kill his former classmates in Middletown, Ohio, just around when AK Steel locked out and replaced workers on strike. “This town ain’t what it used to be. This town used to be a good town,” Danny said.

*****

Yet this narrative of industrial decline its effects on the community conceals why the white-collar opportunities that do spring forward in the Rust Belt are not always taken. One-time steel cities like Pittsburgh and Chicago have largely overcome the decline of their blue-collar origins. They now offer professional pathways in law, finance, medicine, and academia, but only if one is able and willing to get an education.

Economic change has made the tools for education inaccessible to displaced blue-collar workers. Pittsburgh’s Carnegie neighborhood library system is a case in point.

Suzy Waldo, manager of the South Side Carnegie Neighborhood Library, explained that over 10,000 “mill hunkies” came to the library in its opening week in 1909. The library met the needs of the vast working immigrant population by lending technical and mechanical books in English, Polish, German, Lithuanian, Italian, and Slovakian. As one of Carnegie’s 17 neighborhood libraries in Pittsburgh, it served its intended mission: “to engage the community in literacy and learning.”

Then, when the mills shut down in the 1980s, white-collar workers gentrified much of Pittsburgh, including the South Side, pricing blue-collar workers out of the neighborhood. Whereas the old working-class customer base used the library for educational purposes and workforce development, the new professional “lunch crowd” goes to the library for poetry readings and jazz performances. Blue-collar families are effectively shut out of this opportunity for life-long education.

The clinging pride to the Steeler work ethic prevents many blue-collar parents from prioritizing the education of their kids, even though this is key to accessing professional opportunities. Their resistance often keeps their kids out of the world of work altogether.

A 21-year-old lifeguard manager at the pool behind the South Side Library, Jalen Pennix explained older men preach “hard work” and “getting dirty,” even though that life is long gone. “Parents tell their kids to get union jobs,” he said. “If you want to go to college and graduate college, they’re proud of you, but they don’t understand it, so you don’t get the right motivation for it.” Without strong parental support, Jalen said that pursuing higher education is more difficult and less familiar than joining a gang, given how embedded gangs are in the neighborhood.

Parents are key to passing on a work ethic to their kids — in their absence, that work ethic dies. Barbara Barber, a grandmother from Chicago’s West Side, said that a lot of the kids in the neighborhood call her “mom” because their parents are absent or drug addicts. Because gangs often feed, house, and look out for their members, many kids join gangs, so they have people they can call family. And without parental or community encouragement, Barbara said that many kids drop out of school around eighth grade.

Schools alone cannot motivate kids to seek out the white-collar opportunities that conflict with the work ethic and identity of their blue-collar parents. Though the teachers at Jalen’s alma mater, Brashear High, try to cultivate their students’ interests and skills, Jalen noted that they don’t put up much of a fight when they run into motivational problems with students. “Nobody really cares, no one is really striving to do anything,” he observed.

Though Jalen noted Brashear successfully steers most of its students to community colleges, few ever finish, often reverting to gang culture.

It’s almost too easy to craft a story of blue-collar parents and their kids who resist abandoning a way of life that they also can’t preserve. With their work ethic dying, they may try to escape this trap through drugs and gangs. But this path of resistance further forecloses opportunities. Without an education, only the low-wage service and care jobs are left. And these do not confer the recognized dignity of working in the mills.

Blue-collar parents and kids resist the jobs of the new economy because the memory of the mills and what they meant lingers. The mills once grounded communities, built schools, and fed large families. They made the good life accessible through hard work alone.

*****

This sociological picture is probably true in part. But its idealization of the past misses something crucial: Industrial work might not be what it was cracked up to be, and maybe it never was.

In the ghost town of Gary, it seems strange that so few of the workers at U.S. Steel are from the city. Pete Trinidad from Chesterton explained most commute from nearby towns or neighboring states.

34-year-old Gary resident Terrence Woods has a felony from his past involvement with gangs and recently became homeless. A felony conviction is a scarlet letter in many workplaces. But it isn’t the only thing that stopped Terrence from working at U.S. Steel. Terrence didn’t want to. “That’s the last place people decide to go work at,” Terrence scoffed.

In the non-unionized Gary Works plant of U.S. Steel, Terrence knew a lot of mill workers who got injured or died “falling asleep and going there drunk.” Risks aside, many in Gary seem to have changed their minds about the value of industrial work since the mills left. “It’s too much hard work,” Terrence said. “It’s dirty work.” People from Gary would rather work at a Walmart, Family Dollar, or some other service job.

“I told my kids I’d kill ‘em if I ever caught them working in that steel plant,” Danny said. Though he cited the risk of injury and death, he added, “They make good livings, but they don’t have a whole lot of life.” In the sometimes 90-hour workweek, the factory becomes a black hole. “It’s your own greed too. If you want all that money, you can work as many hours as you want. They’re not doing it against their wills, but they look back over the years and think, ‘I could’ve done a lot more than that.’”

Even with his rose-tinted glasses, Pete Trinidad recognized how racking up hours at the mill can affect family life. As union president, he’s helped steelworkers who have told him, “My wife left me. My kids don’t know who I am.”

Steel work doesn’t provide the dignity it once did when it fed families and built communities. Comparing unionized steel work in Chesterton, Indiana to non-unionized work in Gary, it appears the decline of unions has made working in the mills a greater risk to one’s health, family life, and well-being. The decline of economically secure mill jobs has generally undermined the family and community values that made notions of “hard work” worthwhile in the first place.

“If your choice is working in the hazardous waste pit or not working, is not working really an irrational choice?” Klein said.

*****

Like other Rust Belt towns and cities, Sandy Hook, Kentucky, is more than its industry, just like other towns and cities in the Rust Belt. Though industrial jobs probably drew people there in the first place, they are not why people want to stay anymore. They want to preserve their way of life.

Sandy Hook’s amateur genealogist Anita Skaggs, loves to talk and laugh, but she grew quiet and cautious when asked about drug addiction in her community. “We are so much more than poverty,” she said with a kind Southern drawl.

“There’s no place I’d rather live,” Anita’s husband, Gobel, said. “No better place to live and raise your kids.”

Sandy Hook has no major waterways, rails, or highways, but Gobel and Anita like it this way. They are far away from the drugs and crime of the city, not to mention the sirens and odors. Tucked away in the peace and quiet of the mountains where the air is fresh even when it’s grey out, Sandy Hook is nostalgic for the industrial past.

The Kentucky work ethic has stubbornly defied Sandy Hook’s natural obstacles to industry. Farms are perched in every flat plot of land, no matter how small or high up in the mountains. Whether bulldozing coal or welding, Gobel has never worked closer than 45 minutes out of town. Talking about Gobel’s father, Anita said, “Daddy worked as hard for one dollar as for thirty. It was the way he was brought up; you do the job.”

But when the government stopped guaranteeing the minimum price of tobacco and there was no more coal left to mine, the town’s main industries dried up, leaving many without jobs. But the people didn’t want to leave.

Resistance to economic migration can take many forms. Some opt out of work entirely even if it earns them the contempt of the community. Anita explained, “These people don’t want to leave, so they figure out public assistance generation to generation to sustain their way of life.”

Others adapt to the work that is available. A former coal bulldozer, Gobel got technical training and commutes longer distances to be a welder. Anita runs an inn with aims of investing in tourism.

Michael Denning, a professor of American Studies at Yale, said, “Work changes faster than our ideas about work under capitalism, which is different from other kinds of societies in which you might have done the work of your parents and grandparents.” Market forces, indifferent to human dignity, disrupt the values of work that ground communities, forcing people to find new ways to justify why they work.

In a nation believed to have been built on the Protestant work ethic, it is strange to think many Americans are now dropping out of the labor force, and have been for decades. But the context of deindustrialization makes this trend legible. When factories close down, offshore, or automate away jobs, they decrease the bargaining power of unions to increase wages and benefits for blue-collar workers. It is then harder for workers to support their family, contribute to the community, and thus find meaning and take pride in their work. With the blue-collar work ethic thus hollowed out, it’s hard to justify working long hours in arduous conditions. Blue-collar work is more than a job, until it isn’t.

The post-industrial economy is upon us, and there is little hope of going back to the days when industrial labor could create a broad blue-collar middle class. Today, Americans must choose between working at McDonald’s or a computer.

But many in the Rust Belt reject this dichotomy. The retired generation denigrates young people who seem to have given up on “hard work” in the mills and work low-wage service jobs instead. Blue-collar parents don’t attach dignity and pride to college and white-collar work. Many even resort to drugs, and their kids join gangs rather than work at Walmart. While some people adapt just enough to stay where they are, others drop out of the labor force entirely and rely on welfare to support their way of life. As unsustainable as these forms of resistance may be, they indicate that hope for the blue-collar work ethic lives on.

Sandy Hook’s Big Four Store enshrines the hope that the Rust Belt’s future will be like the past. Driving up the mountain, the store appears suddenly at a crossroads. Besides the gravel road, it is the only sign of civilization around. A massive airplane-windmill contraption is suspended on a pole out front. The lone gas pump must have rusted since the 1950s. Inside, Donnie watches a Western on a flatscreen. His antique collection and hand-crafted metal sculptures share the shelves with pickled pork hocks and bottles of pop. Vintage guns and a beehive hang from the ceiling. “They’re not for sale,” Donnie says, standing at the cash register in his overalls with his sun-worn, cheerful face. It is not clear if anything is for sale. At the bottom of the glass cashier booth is a little red hat that reads, “President Trump 2024: Keep America Great.”