Congressional Representative Tony Cardenas, political analyst Estuardo Rodriguez, Smithsonian Director Jorge Zamanillo, and historian Felipe Hinojosa are four men with very different stories. But when it comes to creating the long-coming National Museum of the American Latino, these four men are in agreement: “Latino history is American history.”

In 1994, Raul Yzaguirre, the Chair of the Smithsonian Institution Task Force on Latino Issues, authored a report about the Smithsonian’s attention to Latino history This report found that the Smithsonian Institution “almost entirely ignores and excludes Latinos from every aspect of its operations.” Among this report’s list of recommendations was that the Smithsonian embark on a mission to create a museum that tells the history of Latino and Hispanic people in America.

For years, this recommendation went unheeded. But in 2003, Congressional representatives Xavier Becerra and Ileana Ros-Lehtinen introduced a bill to create a commission that would study the feasibility of such a museum. A year later, Estuardo Rodriguez, political analyst and principal founder of a lobbying organization, known as The Raben Group, formed an informal, volunteer-based advisory group to study the recommendations of the original 1994 report. By 2008, president George W. Bush had approved the creation of the proposed commission, and Estuardo Rodriguez’s informal group was recognized as an official 501(c)(3), newly named the Friends of the National Museum of the American Latino.

The commission published their findings in 2011, declaring “there must also be a living monument that recognizes that Latinos were here well before 1776, and that in this new century, the future is increasingly Latino.” But after these findings, progress on the museum was stalled for years.

California representative Tony Cardenas was sworn into office in 2013 and later became among the principal advocates for the museum in Congress. He first heard about the museum approximately 20 years ago at a conference about Latino political participation. Six years after being sworn into office, after repeated congressional cycles of bills but no concrete legal advance for the museum, Congressman Cardenas decided to champion the bill himself. He worked closely with New York Congressman Jose Enrique Serrano, who had been the bill’s official sponsor. The newly reconstituted bill went through many legislative hearings, the first in May 2019. Here, Cardenas referenced the 1994 report in his testimony, declaring “I think it’s important for the livelihood and the positive existence of the current generations of Latinos and future generations of Latinos that we finally get the respect and the attention that we deserve.”

By the time bill HR 2420 reached the floor of the house, Cardenas made an explicit effort to “show the senate the strong bipartisan support it had in the house,” gaining 295 cosponsors, with 234 democrat signatures and 61 Republican signatures. In previous years the bill had only gained 51 cosponsors, mostly Democrats.

On December 21st 2020, the bill passed in the Senate as part of an omnibus package. However, the legal battle did not end there. HR 2420 instructed the Smithsonian Board of Regents with two tasks, the first of which was to find a building site. But deciding on a site for the museum quickly became an issue of controversy. Democrats believed that the museum would be best positioned as part of the National Mall, the 150 acres of land that stretches from the Capitol building to the Washington monument and serves as DC’s main tourist attraction. But some congressional staffers argued that the National Mall is a completed work of art that should not be further altered. Eventually, a clause was included in the museum bill that prohibited its construction on the National Mall.

“Some Republicans would not allow it [the bill] to pass the Senate had that clause not been included. Once it was amended, the bill was able to get out of the Senate and onto the President’s desk,” explained Cardenas.

The second task for the Smithsonian Board of Regents was to find members for the board of trustees and authorize them to begin the process of curating the museum. Jorge Zamanillo was named the founding director of the National Museum for the American Latino in May of 2022. An archaeologist and a son of Cuban immigrants, he previously served as chief executive officer for the museum History Miami and President of the Florida Association of Museums. When he first joined the board in May, the Smithsonian was investigating 27 possible museum sites on and off the National Mall. “Most of the people that come to Washington, DC are visiting the monuments and the museums along this area…visibility, location for public transportation, ease of access, are all different things we look at.” But the museum’s location was not just about its convenience for tourism, Zamanillo explained. “You need public spaces for exhibits. You also need a backup house. You need food services, you need an auditorium, you need restrooms, you need collection space, offices.”

The investigation landed on the Tidal Basin, a site located on the National Mall just west of the Holocaust Museum and south of the Washington Monument. With a location on the National Mall in defiance of the founding bill’s original provisions, another congressional effort was needed.

In August of 2024, almost two years after the investigation was concluded, bill HR 9274 was introduced to Congress to allow the construction of the American Latino Museum on the National Mall.

As Congressman Cardenas and Estuardo Rodiguez fight for the museum on the National Mall, Zamanillo and his Board of Trustees embark on their fundraising journey. Preliminary estimates place the museum’s cost at over a billion dollars. The Smithsonian has been tasked with independently raising about $500 million, while Congress is expected to make up the rest. Donors are of utmost importance to this effort. “It can be a little daunting, but it’s actually kind of exciting.” Zaminillo comments, “It’s really about building relationships with [donors]––they need to believe in the story, that they’re doing the right thing, that they can trust us.”

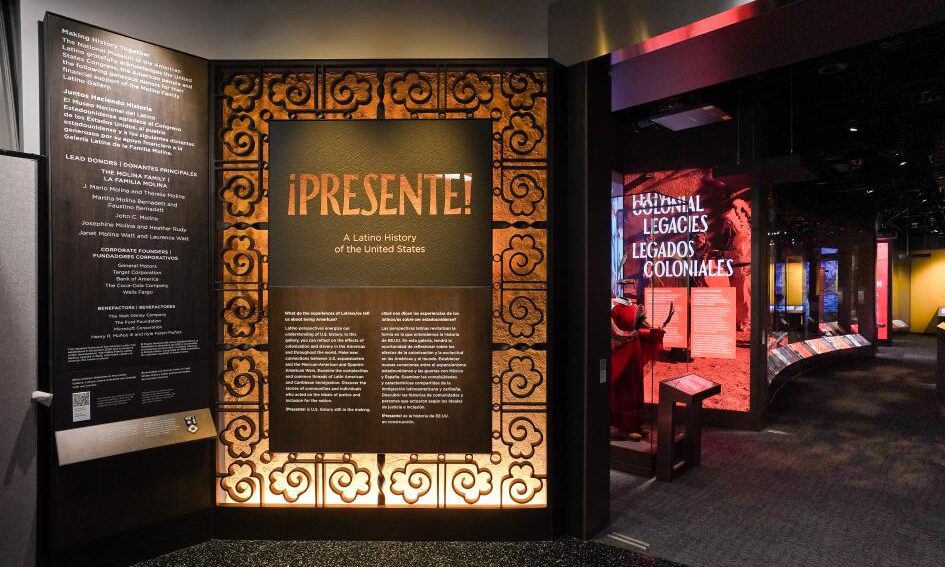

Another focus of the Board is the curation of small “sneak peak” exhibits, which are previews of future museum exhibits to build anticipation for its opening and assist in fundraising efforts. In June 2022, the Molina Family Latino Gallery opened their “sneak peak” exhibit, ¡Presente! A Latino History of the United States. The exhibit displayed everything from colonial legacies of Latin America andLatino contribution to American culture to stories of Latino immigration to the United States.

There was an explicit emphasis on variety—from languages spoken, to struggles faced, to physical appearance. Not everyone was fond of the display, however. A group of Latino Congressman took action towards defunding the Museum in the summer of 2023. They spoke out against the exhibit for portraying Latino Americans as victims and for erasing the histories of Latinos who benefited from American Liberty, with one Congressman even calling it “a Marxist portrayal.”

As ¡Presente! had its time in the spotlight, The Smithsonian was working behind the scenes on another “sneak peak” exhibit. This exhibit would focus on the social and political movements of the Young Lords and the Latino Freedom Movement of the late 20th century.

Felipe Hinojosa, a History professor at Baylor University, was invited to help curate the new exhibit. When asked why exhibits such as these are an important part of the Smithsonian’s mission, Hinojosa responded, “Latinos often get seen as perpetual foreigners, as people that are newcomers, as people that don’t give much value to the nation, or we get viewed as dangerous or a public menace. These exhibits I think serve to correct that history and inform and educate the public about how Latinos have shaped American democracy.”

Hinojosa was given a private tour of the ¡Presente! exhibit before it opened. “I got chills… a sense of pride.” Hinojosa feels that the negative reaction to ¡Presente! had more to do with politics than the content of the exhibit: “I think what was really frustrating is that you had a lot of people with zero experience that were not very qualified to make these kinds of assessments, basing their assessments based strictly on the political climate that we’re currently in.” Not only did he stress the professionality and expertise of the curators, but he also argued that exhibits such as ¡Presente! are “in fact very representative of the American experience…these are communities that immigrated here, searching for the American dream. And that American dream failed them. They had to fight for their rights and their representation.”

In September of 2022, three months after ¡Presente! opened, Zamanillo and his board made the decision to cancel the exhibit on Latino Youth movements, and replaced it with one on Latin music. Hinojosa and his colleagues, who had spent two years curating content, were sorely disappointed. “This was going to be really special. My heart was broken,” he said. Zamanillo told reporters the Board had decided that an exhibit on Latino Youth movements wouldn’t raise the necessary funds. Although Zamanillo stated the decision was not a result of political pressure, shortly after, articles came out expressing an uncertainty for the future museum’s content, and how much the political climate may influence it.

Although Hinojosa highlighted the extensive survey research done by the Smithsonian before deciding on “Latino Youth Movements,” Rodriguez explained, “you’ve got to think about how to attract the most people possible… Zamanillo’s decision was in the best interests of the museum.”

“There’s so many different perspectives that we bring in, but at the end of the day, we have a lot of commonalities shaped by our experiences here in the United States as Latinos, and that’s what’s really important,” Zamanillo commented. He emphasized that with the space of the museum, there will be opportunity to tell a variety of stories encompassed by the Latino experience. “When we open the bigger museum, we’re going to have over 100,000 square feet of public space, so you can imagine the number of stories that you could tell in there, and the contrasting viewpoints.”

Although the struggle to build the National Museum for the American Latino on the National Mall is still ongoing, the Smithsonian has begun the curation, research, and funding efforts necessary to create the first museum to be dedicated to the history of the largest ethnic group in America. A few months ago, the journey to create the museum turned 35 years old, with many key contributors whose passion for their heritage and a dedication to their representation has served as the fuel behind their effort. They carry on the baton to eventually pass it on to the next generation of activists, lawmakers, and experts who will take on the next big challenge.