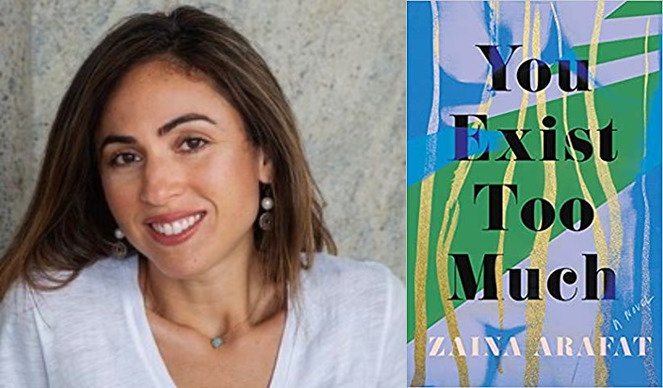

Zaina Arafat is an LGBTQ Palestinian-American writer. She is the author of the novel You Exist Too Much, which won a 2021 Lambda Literary Award and was named Roxane Gay’s favorite book of 2020. Told in vignettes that flash between the U.S. and the Middle East—from New York to Jordan, Lebanon, and Palestine—You Exist Too Much traces its protagonist’s journey for two of our most intense longings—love, and a place to call home. Arafat’s stories and essays have appeared in publications including The New York Times, Granta, and The Believer. She lives in Brooklyn and is currently at work on a collection of essays.

You Exist Too Much is a story about healing. Did writing and publishing the book help you heal?

Yes. I think writing emotionally and physically affects you because you write your way through something. Something that obstructs your ability to move forward in the world. For me, the issues that the protagonist is grappling with—her sexuality, her biculturalism—are issues I also relate to as a Palestinian-American queer woman. I can definitely say that who I was when I started writing this book and who I am now is different. The book has been a journey that has been a bridge for me to get to where I am now, and I have transcended a lot of pain.

While the narrator admits herself to a treatment center to get help for her “love addiction”, what are ways of healing without institutional support? How can we take care of ourselves in a world so fraught with violence?

Forming communities is hugely important for healing and taking care of oneself. The communities in my own life, such as my writing community, my queer community, my fellow Arab American community, have been a huge source of strength and healing. We’re in a space in a world that’s filled with so much pain, violence, and horror. Without community, I think I would feel so rudderless and so much more helpless. I also think taking healthy actions can be really helpful towards healing. I like to run and I’m participating in a 5k this weekend, and that is really uplifting and nourishing. I also think family, even though it is an institution in some sense, is important because family teaches you how to find the good in and multi-dimensionalize people.

On that note, family, and especially motherhood, plays a crucial role in You Exist Too Much. How does your family influence your work, and how did they respond to the book’s publication?

So much of the book is about intergenerational dynamics between immigrants and first generation Palestinian-Americans, which was influenced by my growing up. My mom and dad had a different culture and spoke a different language than myself. Interestingly, they were supportive of the book. They’ve also been incredibly supportive of me as a writer, which is amazing and shocking, honestly. I also hoped that this book could be relatable to other people who are the children of immigrants, outside of the Palestinian community.

The exploration of how culture exacerbates the narrator’s conflict with her sexuality really stood out to me, especially the line: “A relationship with a woman meant failure: I had failed to get a man, failed to find something normal, failed to not be pathetic.” When building this novel, how much of it did you want to be driven by sexuality?

Sexuality is obviously at the heart of the book in many ways. The narrator discovers and accepts her sexuality. She falls in love with women that are unattainable because that’s the safest way for her to express her sexuality. At the same time, the narrator comes from a culture where it feels unacceptable to inhabit her sexuality in a genuine way. Being Palestinian, Muslim, and queer is not necessarily compatible. But also, I think sexuality is a symptom of her relationship with herself. The narrator has a lot of internally-imposed shame. Her sexuality is an outward manifestation of that shame and her fear of not being acceptable.

Recounting the intifada that she experienced as a six year old, the narrator says, “But I remember. Perhaps because I want to. I can just as easily forget when I want.” This is such a fascinating line, and I wonder how you came to it. How does personal memory situate itself in historic memory? Does memory contribute to the alienation that the narrator, as an immigrant, feels?

That lineharkens to the idea that memories are created by stories—stories that you’ve heard from your parents that they lived through and were traumatized by. Those experiences trickle down to you. It can be hard to know what belongs to you. What is your personal memory versus a story you’ve been told? What pieces of memory stick to you? And what do you choose to forget and block out? I think that the narrator intentionally forgets often, because she keeps repeating the same destructive patterns. She can remember when she wants to and forget just as easily. It’s a cycle of willful forgetting. This also speaks to this idea of what belongs to you. What are your personal traumas? What are your collective traumas? How do these two get mixed up or confused or parsed together when they should be parsed apart?

You Exist Too Much splices the narrator’s present-day life with flashbacks from her past.

The narrator explains her parents’ relationship with a metaphor about Hamas and Israel and defends herself against other people’s misunderstandings about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict at the treatment center. How do you accept, or have you accepted, the need to repeat and to reexplain yourself and your history to people?

I have accepted it. Since October, people have asked why they have to do the emotional labor of explaining what’s going on. People often say that it’s not their job to explain, whereas I feel like it is. Because otherwise, it will never be explained. It’s frustrating, in some sense, but I hope that I can explain in an artful and, at times, humorous way. The metaphor with the narrator’s parents being Hamas and Israel is not funny in the current context, but it’s meant to be a cheeky shorthand that conveys information about these two factions. I’ve accepted the need to explain, and I will do that explaining if I have to, until the day I die. I feel like the benefit of being a Palestinian-American, and not being seen as a typical Palestinian that people often immediately shut off, is my ability to get through.

You said in an interview with PEN America that once, an editor struck the word “Palestine” from your writing and wrote in the margins, “Palestine does not exist.” Have you had similar experiences since then? How has the publishing industry been affected by the escalation of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in the past months?

Yes, I have had similar experiences. Not to that degree of blatancy, but there have been experiences that have been very problematic. Editors have reached out to me and asked me to write things now, which is fantastic. Usually, it’s with an empathetic sort of desire to hear from Palestinians or the Palestinian diaspora. At the same time, I’ve been told that several editors or publishers are Zionist and are not going to publish my work. I think that’s even more the case right now.

You also mention Edward Said in the book. How has Said’s, or other Palestinian writers’, work influenced your writing and teaching practice?

Said has influenced me to have the courage to be out here writing as a Palestinian. He has influenced myself and other Palestinian authors like Randa Jarrar and Hala Alyan to call ourselves Palestinian. Edward Said is a genius when it comes to how Orientalism is so unbelievably pervasive and limiting. I’ve thought a lot about that as a writer because I was expected to play into that Orientalism. When I was submitting my book, there were requests from agents or editors to add more camels or more spices because they were exotic Orientalist imagery. And I was just thinking, gosh, that’s exactly what I’m trying to push against. I don’t want to tell a story that falls into an Orientalist framework.

What are you currently working on?

I’m writing an essay collection and another novel about an artist, set between Europe and the Middle East, as opposed to the United States and the Middle East.