The modern environmentalist is an intellectual individual, armed with vast amounts of data, robust environmental theory, and no shortage of protest tactics. They recognize their role in the climate crisis, opting to switch to plant-based diets, transitioning to public transportation, buying second-hand apparel, protesting for climate justice, and learning to recycle more effectively. Having assumed personal responsibility for their environmental impact, they do not fail to then look at the larger, systematic problems. They look to “carbon majors” – 90 companies including investor-owned firms such as ExxonMobil, state-owned companies, and government run industries, all of which are responsible for 63% of cumulative global emissions of industrial carbon dioxide and methane from 1751 to 2010 – as leading culprits of the climate crisis and work to hold them accountable.

The questions of how individuals and carbon majors ought to act towards the environment are more or less matters of general consensus. However, as a budding environmentalist, I struggle to understand how to perceive community-level patterns of energy consumption and sustainability – how to perceive and act towards the actions of others. The scope of the community varies. On a global scale, the demand for plastics has taken off during the COVID-19 pandemic. On a national scale, American car culture remains a great obstacle to a clean energy transition and for public health. On a local scale, bus stigma in major cities and a general aversion from public transportation remains a missed opportunity for sustainability.

For passionate environmentalists, it might be easy to write off certain groups of people bound by an unsustainable practice as being beyond persuasion. I’ll be the first to admit that I felt great frustration during a 2016 Trump rally, where citizens of West Virginia passionately held up signs saying “Trump Digs Coal,”and anointed the billionaire with a hard hat. The facts are clear, and coal has long been on an inevitable decline that bodes poorly for coal miners and well for the environment. Thus, their continued support for coal conflicts with my still-developing environmentalist approach, one primarily informed by quick facts, computer models, and IPCC reports.

A closer inspection of coal culture and how it came to be elucidates how community values can sometimes be “irrational” but meaningful and valid nonetheless. Notions of culture in environmentalism complicates the idea of writing off groups of people who engage in unsustainable practices. Coal culture, specifically, exposes the true climate antagonists and demonstrates their influence, as the formation of this identity is one that is inextricably linked to corporate pull and well-funded manipulation. It reframes coal miners as victims of darker systematic devices, and recenters companies as responsible for unsustainable social behaviors.

The Corporate F(o)unding of Coal Culture

The relationship between communities in Appalachia and coal companies situated there is admittedly an illogical one. The coal industry has been responsible for damaging the region in many ways without providing enough benefits to counterbalance these externalities.

Coal operations such as mountaintop removal have resulted in the decimation of ecosystems and waterways. From 1985 to 2001, the practice of filling valleys with mountaintop debris has resulted in the burying and disruption of around 724 miles of streams in Appalachia.

Coal-sludge dams, pools of black chemical sludge produced by coal extraction have also led to devastating tragedies in Appalachia. In 2000, Martin County, Kentucky saw an impoundment collapse that led to the spilling of 250 million gallons of coal waste and the pollution of over 70 miles of waterways in West Virginia and Kentucky. This incident echoed the similar 1972 Buffalo Creek Disaster, which claimed the lives of one hundred twenty-five people and left thousands homeless.

While the environmental effects on towns in Appalachia are clear, the benefits reaped are not. Since Donald Trump’s 2016 promise to bring coal back, over 41 mines have shut down. In 2019 alone, U.S. coal production decreased by 6.6%, and in 2020, it was projected that coal production would be down 25% compared to 2019. That same year, jobs in clean energy came to outnumber those in the fossil fuel industry by 3-to-1, and this industry’s job opportunities are only expected to grow under the Biden administration.

Despite the unkept promise of coal’s comeback, Appalachia voted overwhelmingly red in the 2020 general election. The pride of being a coal miner, despite the seemingly inevitable end of coal also persisted. The Columbus Dispatch, in an interview with former coal miners in Perry County, Ohio, noted how working in the mines was a “point of pride” and that many would return to the mines if they could.

The continued legitimacy of coal culture in Appalachia despite the lack of benefits for its communities is one at odds with the logical processes of the modern environmentalist. To gain a better understanding of what drives popular support of the coal industry, researchers interested in environmental sociology have conducted ethnographic studies where they interview and live alongside hundreds of coal-invested people. One such study characterizes coal culture as revolving around a faith that the coal industry will provide good jobs, that renewable energy is less affordable, that coal mining embodies community values, and that the symbol of the miner resists urban encroachment.

The tenets of coal culture are clearly out of touch with the reality of the coal industry and what it has to offer. As demonstrated above, the current economic reality of energy in America runs counter to the idea that the coal industry can provide well for its employees. Because of these illogical disconnects and the vast poverty plaguing towns in Appalachia, sociologists concerned with this coal question have argued that industry transformed Central Appalachia into an “internal colony.” This term emphasizes the tendency of coal companies to expropriate community wealth while neglecting fair wages and community reinvestment of profits.

In a widely cited study of coal towns in West Virginia, Shannon Bell and Richard York describe past and present methods of cultural manipulation employed by coal companies against residents. Beginning with land acquisition, Bell and York note how many purchases were made by eager entrepreneurs coming outside of Appalachia. Their knowledge of the potential wealth of the land and the inhabitants’ lack thereof led to the procurement of literal mountains in exchange for values as minimal as a hog rifle. Furthermore, once coal companies had purchased contiguous and large enough tracts of land in this fashion, they would build and retain ownership of essential services such as houses, streets, schools, churches, sanitation systems, medical offices, and company stores. Many companies went so far as to enforce worker payments through “scrip,” their own monetary system that was only redeemable within a given town, stifling any prospects of social mobility.

These tactics, though no longer employed, contributed to the enduring myth of coal companies as being the backbone of many towns in Appalachia, inextricably linked to a town’s history and culture. The manipulation of culture has since changed in character, but persists nonetheless.

In 2002, the West Virginia Coal Association (WVCA) formed a “grassroots organization” called the Friends of Coal, which aimed to educate citizens about the coal industry and its role in the state’s future. Having studied regional and national newspapers, the Friends of Coal website, the West Virginian Coal Association’s website and having gone into the field, Bell and York concluded that the WVCA was able to co-opt cultural icons and use money to forcibly install themselves into the cultural identity of Appalachia.

As a part of their strategy to earn the trust of residents, Friends of Coal appealed to town pride and virtues such as the idea of a champion, the provider icon, and the outdoorsman tradition. This was done by the strategic hiring of reputable townsfolk such as College Football Hall of Fame star Don Nehlan, professional bass fisherman Jeremy Starks, or retired air force general ‘Doc’ Foglesong. These spokespeople appeared in ads playing to their background and celebrating the importance of coal mining. For instance, Foglesong states in an ad emphasizing coal’s role in upholding our nation’s stability, “If these miners didn’t produce coal, our nation would be in trouble… America needs that energy – today more than ever.” In a similar vein, Starks appears in a riverside ad, explaining that “Scientific tests have shown that this water quality is better now than it’s ever been. And this is after 22 million tons of coal have been mined in nearby land.”

Coal interests groups were able to engender enthusiasm and vindicate the environmentally hazardous externalities of coal production through methods besides advertisements. Leveraging its capital and influence, Friends of Coal was able to implement an education curriculum called the CEDAR program in various public schools. The program sought to “socialize school children in the southern coalfields to an ‘understanding of the many benefits’ the coal industry provides in daily lives.”

The CEDAR program consisted of materials prepared by the WVCA staff. Although optional, teachers were offered attractive grant money to create units on coal that used the CEDAR materials. Furthermore, three teachers having the “best performance” would be eligible to win cash prizes,and the CEDAR program also independently gave ten $1,000 scholarships to students from five participating coalfield counties.

The money used by the WVCA to fund its culture-forming activities is not negligible. At the same time, it is far from unprofitable and can be perceived as constituting a type of “cultural commodity.” Critical traditions such as Marxism and feminism analyze the role that ideology plays in perpetuating the oppressive status quo, and they note how capitalist societies produced “cultural goods for mass consumption” such as Hollywood movies. The socialization of children and adults in coal-connected towns falls under this tradition. Coal companies stress an economic identity in order to legitimate their operations; once the culture of coal was established, companies felt that they could rely on continued popular support deriving not from a rational assessment of benefits and burdens, but from tradition and history.

Broadening Coalitions

Reflecting back to 2016, my initial frustration regarding the West Virginia Trump rally stemmed from the self-destructive support that coal miners were giving to their poison. The fact that impoverished, manipulated workers could support a billionaire with no lived experience of the working class struggle and one who specifically supported the already wealthy coal barons harming Appalachia communities seemed ludicrous.

However, a fixation on reason and logic when considering natural resource use in America can fall short of the intersectional imperatives of environmental justice. Culture can clash with logic and technocracy, and this consideration should factor into how we advocate for climate justice.

Today, the environmental movement continues its war on coal. The Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign has meaningfully contributed to the retirement of many coal plants in America and movement away from fossil fuels is a recurring tenant of environmental groups. During the 2016 presidential campaign, Hillary Clinton said at a March 13 CNN town-hall event, after talking about her approach to energy jobs: “We’re going to put a lot of coal miners and coal companies out of business, right?” Clinton proceeded to lose several Ohio counties that election cycle.

I, by no means, seek to vindicate or defend the coal industry nor its operations. A liveable planet categorically calls for the rejection of fossil fuels. It is also not unreasonable to feel some degree of antipathy towards coal miners, who aside from their stance on coal, endorsed many other controversial political positions by voting for Trump in 2016 and 2020. However, noting the deliberate cultural engineering by coal companies and the subsequent burdens beared by coal miners, I have since gained a newfound appreciation and understanding of their psyche.

And this appreciation is not useless. It is not the case that the environmentalist movement’s affront on coal is inextricable from an affront on coal miners. The subordination of towns in Appalachia by large coal companies and a reassignment of blame calls for measures that also take this into account. Such measures, such as retraining, have already been proposed, and more recent scholarship argues for greater support, such as subsidizing local communities and helping to address the re-employment problem well.

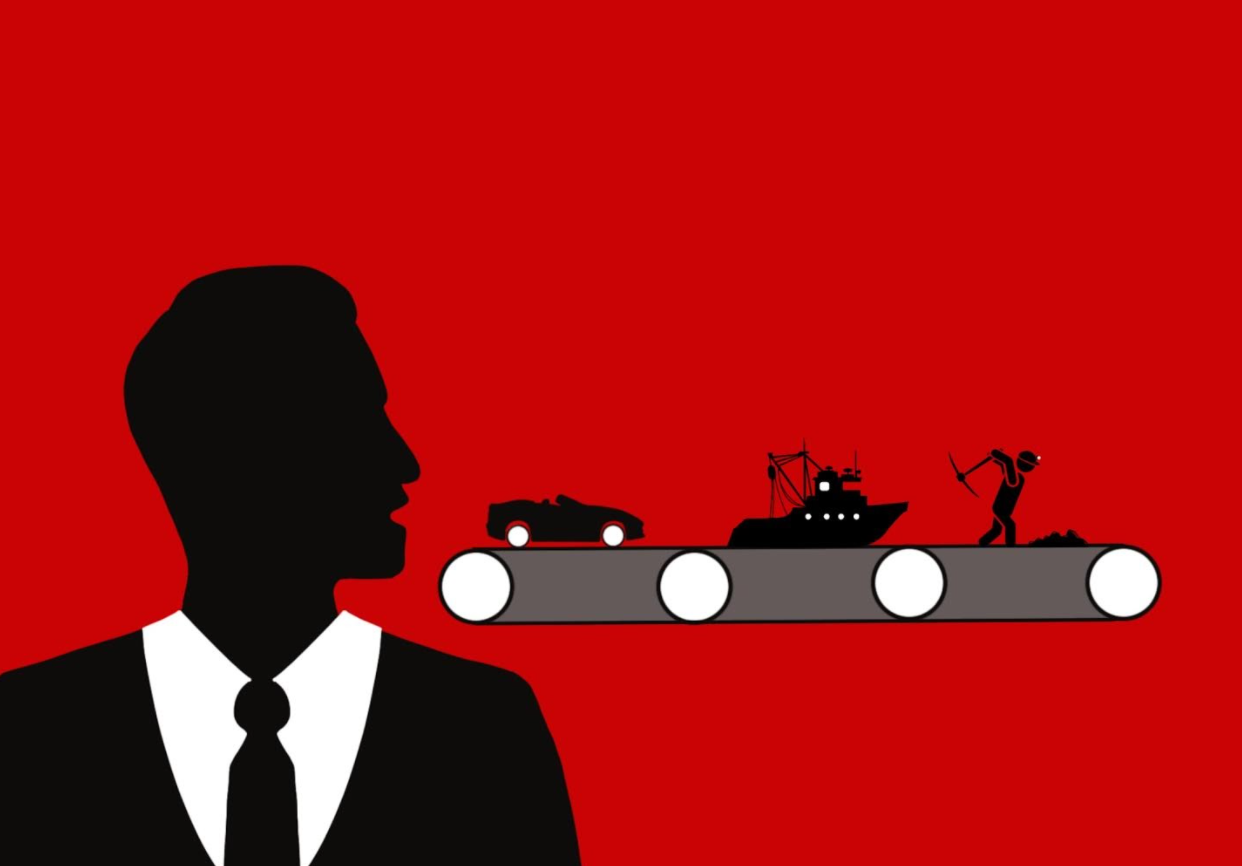

The coal question has helped me to redirect my animosity. Whereas the visible demonstrations of people in favor of coal, or of blue-collar workers romanticizing cars serve as easy targets for environmental outcry, profiting companies and their psychocultural warfare are much harder to identify. The history of company towns and more contemporary co-optation of community icons speak to this notion of subtle tactics employed by industry. The goal should be thus, to reclaim all types of histories and cultures, and to think critically about where they came from. Noting this and the power of industry can serve to reclaim alienated groups of people at different levels of oppression. Achieving such a feat would build a more powerful, more nuanced, and more inclusive coalition of people against climate change.