As we study in university, passing daily through an academic institution (toward our next station in life), Rousseau suspects we are only contributing to the deterioration of societal morals. “Morals” for Rousseau translates the French word mœurs, which is used in the general sense encompassing social manners, norms, and custom. From a thinker of the Enlightenment period, Rousseau’s stance inspires a double take.

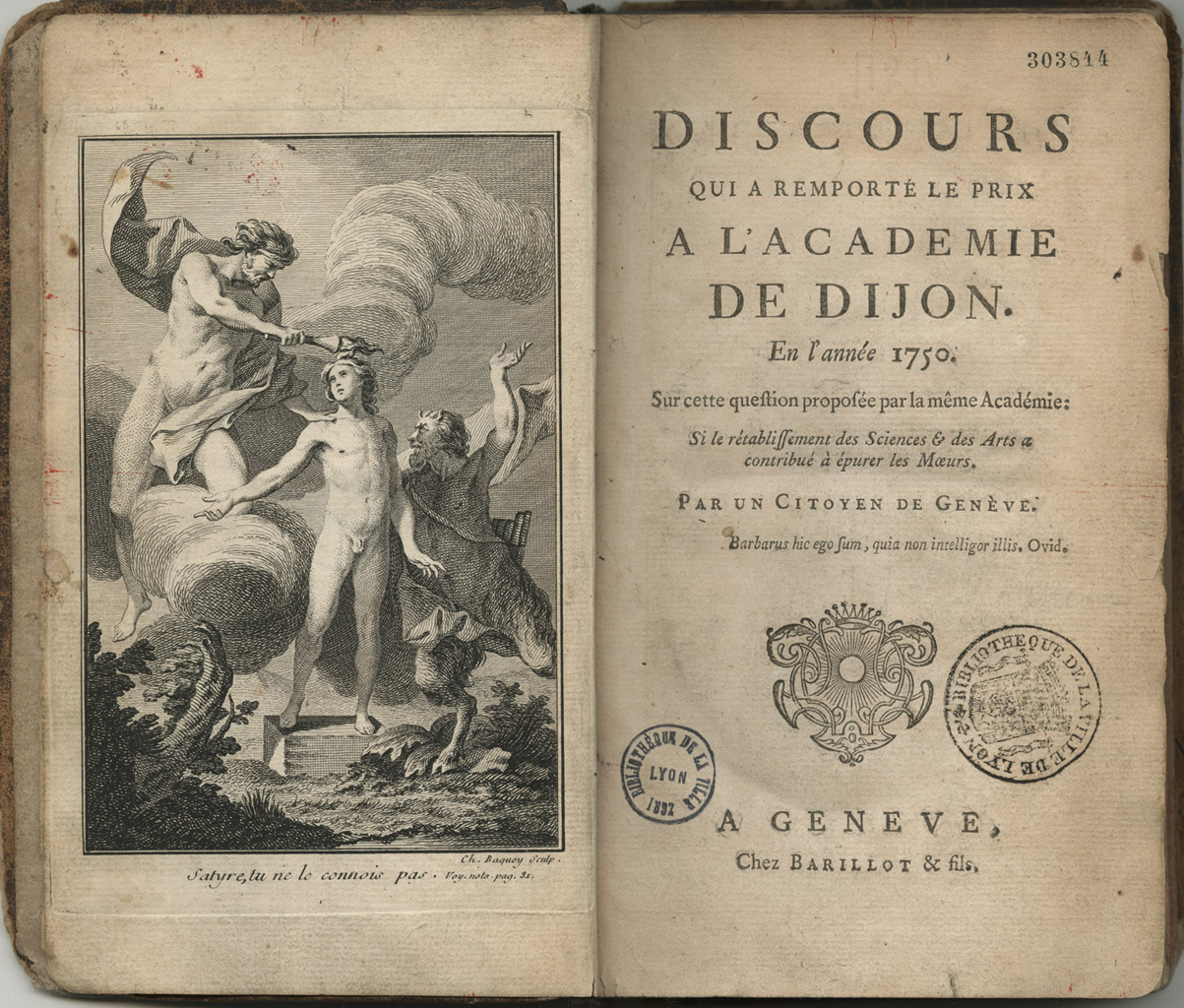

A controversial thinker even during his time, Rousseau gained fame and notoriety following the publication of his First Discourse, otherwise known as the Discourse on the Sciences and the Arts, famously arguing that the sciences and the arts corrupt morals. This article is the first in a series reading and recontextualizing various political philosophers for the present day.

…

Under gilded ceilings in lavish ballrooms, meeting elites in Paris and observing their social courtesies, Rousseau lamented the splendor of his time. Just as we, in the present, are celebrating the pursuit of innovation and new amenities, his society was exploring the heights of intellectual achievement and great wealth in the 1700s at the dawn of the Enlightenment. But Rousseau was nervous.

The cause for Rousseau’s nervousness is this exact sense of progress – in particular, the restoration and rise of the sciences and the arts. In the First Discourse, he writes, “Our souls have been corrupted in proportion as our sciences and our arts have advanced toward perfection” (14).

Importantly, he saw the corruption as a deviation from man’s natural roots, which were ignorant, simple, and virtuous. The source of this corruption is rampant deception, characteristically displayed in the engaging manners, pleasantries, and propriety in his social setting. On the past, Rousseau writes:

Before art had fashioned our manners and taught our passions to speak a borrowed language, our morals were rustic but natural… Human nature, at bottom, was not better. But men found their security in the ease of seeing through one another, and that advantage, of which we no longer sense the value, spared them many vices (13).

Since then, society has put on extravagant appearances, introducing manners and activities of increasing civility. People demonstrate their sophistication with sprinkles of refined taste and agreeableness, “in a word, the appearance of all the virtues without having any of them” (12). Such is the prevalent deception.

…

Rousseau believes this deception is fueled by the sciences and the arts, because they ultimately serve human pride. This notion is not a new one, as it has been transmitted by ancient myths of Prometheus and the Tree of Knowledge. Rousseau offers his own energetic and acerbic explanation for the harmful root of knowledge:

… human knowledge will not be found to have an origin that corresponds to the idea one would like to have of it. Astronomy was born from superstition; eloquence from ambition, hatred, flattery, lying; geometry from avarice; physics from vain curiosity; all of them, and even moral philosophy, from human pride. The sciences and the arts therefore owe their birth to our vices (23). [emphasis added]

The pursuit of knowledge is steeped in vanity. I had been told that a university administrator remarked, “The lifeblood of faculty is envy.” While there exist shining examples of genuine curiosity, anecdotes in academia also brim with accounts of toxic competition, from getting publications, citations, and honors for one’s work. Rousseau exclaims, “O rage for distinction! What will you not do?” (25).Perhaps envy in the academy is not an accident, but a necessary consequence of the fundamental self-motivated reason for learning – to gain renown for one’s name (within our outside academia, in or beyond our current age), even occasionally at the expense of virtue.

Rousseau thinks the sciences and the arts are a waste of time. He writes, “Born in idleness, they nourish it in their turn, and the irreparable loss of time is the first injury they necessarily do to society” (24). An intuition for this claim lies in how intellectual activity is an alternative to work. Sitting at my desk before the bedroom window and hoping to escape from my internship deadlines, I have often wished to hide in a faraway country, reject all work, and lie on a prairie to read. Even last year’s city lockdown had a healthful effect; society was turned upside down, nobody expected anything from me, I could just gaze at the ceiling and endlessly contemplate metaphysics. Was I being a functional, contributing member of society? I highly doubted it. As for the serious scientists or writers making their life’s work, in proportion to the people in the field and the cumulative hours spent, how difficult, and thus perhaps how useless, is the intellectual quest for a person to society. Rousseau writes, “Reexamine, then, the importance of your productions… tell us what we must think of that crowd of obscure writers and idle men of letters who devour the state’s substance at a pure loss” (25). Unlike the non-essential workers of society (it is astonishing the space they occupy today), the nurses and plumbers might actually be doing something worthwhile with their time. Yet we stream enthusiastically into non-essential paths.

…

Evils still worse accompany the sciences and the arts. “One of them is luxury, born like them from men’s idleness and vanity” (25). It is eerie that this sentence, which could easily feature in the New York Times today, was written centuries ago: “The ancient politicians spoke constantly of morals and virtue; ours speak only of commerce and money” (26). Rousseau penned this statement more than a century before Marx wrote on capital; it argues that society’s malaise is luxury, whose source lies much deeper, and earlier, in that misguided, fanatic intellectual chase, encouraging vanity and idleness.

Why is luxury bad? One might consider, as examples of luxury, fine art, haute couture, smartphones, even Tesla. Representing the pinnacle of art, craftsmanship, and innovation in science and technology, for some, luxury is even an end to pursue.

Rousseau concedes luxury may seem good, but argues there must be a trade-off. Luxury may be a sign of wealth, and even increase it. However, it is notably separate from virtue and different from good morals. What is precisely at issue in this question of luxury is: “to be brilliant and transitory, or virtuous and lasting?” (27). When one’s mind is mixed in with other motivations – like wealth – apart from natural virtue, one is already distracted, displacing the focus on the good.

“Every artist wants to be applauded” (27). Rousseau gives the writer Voltaire as an example of human pride resulting in the dissolution of morals. If born into a time of corrupted tastes, a person would lower his genius to the level of his age, in order to pander to validation and esteem. Rousseau asks Voltaire, “how much you have sacrificed manly and strong beauties to our false delicacies?” As for people of extraordinary talent and firmness of soul, who refuse to yield to the genius of their age, Rousseau decries, “woe unto him! He will die in poverty and oblivion” (28). Even the wise are not insensitive to glory. What is in sight is no longer the good, but the brilliant.

Thus, people exchange appearances for substance. “Incessantly it is customs that are followed, never one’s own genius” (13). People begin to deceive.

…

What is virtue —what is this path from which Rousseau thinks we shall never deviate? He does not quite articulate it in the First Discourse as he would in his second. However, he does not seek to identify and justify virtue because he believes we already know intuitively. “It is a lovely shore, fashioned by the hand of nature alone” (28). We have known it before, with our original simplicity and ignorance, without the sciences and the arts.

…

Rousseau does not dissuade us from intellectual pursuits. He is not denying all genuine curiosity, but believes the number of people pursuing the sciences and the arts are excessive. He laments the unnatural incentivization of all men to pursue academic achievement. “Those whom nature destined to make its disciples need no teachers. The likes of Verulam, of Descartes, and of Newton” (34). For instance, Rousseau will likely find the current oversupply of Ph.D.s regrettable, but predictable. Have we been incentivising people down academia, because of social esteem, even if society really has no need for them, and they would not have naturally gone into it? Rousseau wonders if some of them could have made great cloth makers.

Forced down specific forms of civility, propriety, and achievement – the artifice of the age – society has been blinded by appearance and corrupted its morals. The high-achieving elites seem to be those who pretend and fool people just enough to get to the next station in life. As the sciences and the arts progress, we just deceive in more artful ways, learning to tell (and tell others we know) the Bordeaux from the Bordelais.

…

In the William F. Buckley Jr. Program at Yale’s summer seminar on Rousseau, where I read the First Discourse as a participant, our professor emarked how a roomful of Yalies suddenly sounded like Trump supporters, claiming that academics merely put on appearances. How do we argue against that incendiary instinct, which Rousseau had so urgently described some eons ago?

The most eloquent counter argument to defend the pursuit of knowledge may be that of interrogating oneself: what, truly, drives you to know? Is it curiosity, altruism, wealth, power, pride, or a mix of them all? May it be that each of us who aspire to know watches over ourselves and strives to make ourselves worthy, through useful works that benefit society and irreproachable morals by our own intuitive standards.

In his submission (of the First Discourse) to the Academy of Dijon for a prize, Rousseau writes cheekily, “there is, regardless of the outcome, a prize I cannot fail to receive. I will find it in the depths of my heart.”

Page numbers (in brackets) are taken from The Major Political Writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau: The Two Discourses & The Social Contract, translated and edited by John T. Scott.