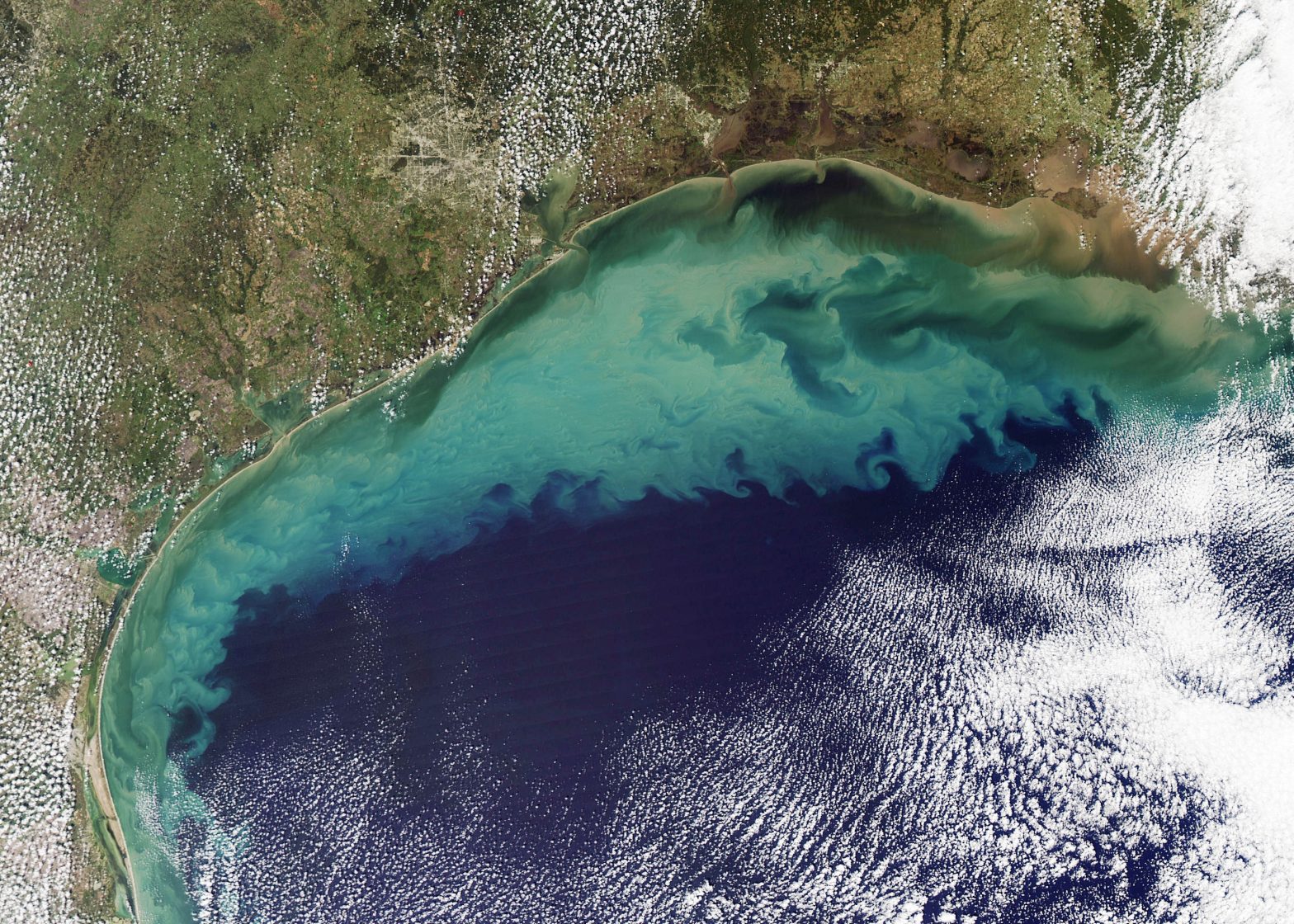

Pollution pouring into the Gulf of Mexico has created a harrowing scene: rose-colored algae covers the seafloor, and decomposing wildlife blankets the shore. An ever-expanding “dead zone,” where low dissolved oxygen kills or displaces undersea life, now occupies a record 6,334 square miles.

The crisis is fueled by fertilizer runoff from Midwestern farms washing down the Mississippi River. Excess nutrients found in fertilizer overload Gulf waters and promote the rapid growth of algae. When the algal bloom eventually settles to the bottom and begins to decompose, it depletes dissolved oxygen and causes the dead zone where oxygen levels are not high enough for fish to survive.

For those who live along and make their living off of the Gulf, the dead zone is devastating. “The Black Bay and Breton Sound areas and American Bay and California Bay used to be just an unbelievably productive oyster fishery back there,” said Chris Nelson, a fourth-generation fisherman and current president of Bon Secour Fisheries, a large seafood purveyor in Louisiana. “It produces virtually no oysters anymore.”

Pollution has overwhelmed the diverse marine ecosystem that once thrived on the Southern coast. “Where there’s high nutrient Mississippi water spilling into the area, the oysters either don’t reproduce, don’t survive, or don’t grow,” said Nelson.

He wonders why regulators are not doing more to address the problem. “I have an [National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System] permit here to limit the pollution that I can create in my local surface water. Why is agribusiness upstream of the Mississippi River not required to limit nutrient loading?” Nelson asked. “Limiting nitrogen and phosphorus nutrients that cause the water of the Mississippi River to be harmful downstream, that can have an effect tomorrow.”

In 2001, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and twelve Mississippi River basin states agreed to work together to reduce two-thirds of the dead zone by 2015, which would require a reduction in nitrogen runoff from the Midwestern Corn Belt by 45%.

That deadline has now been extended to 2035. Today, the zone is 2.8 times larger than the 2035 target set by the task force.

Don Scavia was a member of the Federal-State-Tribal task force that worked with the EPA to create the 2001 Action Plan. He noted that runoff into the Mississippi River has stayed constant for 30 years, revealing the failure of the 2001 plan and similar actions.

Scavia argued that efforts to clean up the Gulf have fallen short because controls on nutrient pollution from agriculture are weak. What is needed is stronger political will. “Many billions of dollars have been spent through the farm bill on conservation measures, but the nutrient load to the Gulf (and the Chesapeake and Lake Erie) have not been reduced much, if at all,” he said.

Before his work with the EPA, Scavia led an integrated assessment during the Bill Clinton administration to analyze the causes and remedies for the Gulf dead zone, pointing to Midwestern corn production as the primary cause. Corn production has expanded over the past decade due to the increasing use of corn ethanol, or biofuel. Biofuel, fuels derived from plant materials rather than limited crude oil and natural gas supplies, have been touted by some as a “carbon neutral” replacement to gasoline or diesel. However, a growing number of scientists, researchers, and activists believe policymakers have overlooked serious environmental harms associated with biofuel production such as changes in land use and nutrient pollution.

Scavia expressed the difficulty of conveying such concerns to lawmakers in the face of large agricultural interests. “The consequences of an overload of nutrients in our waterways have negative economic implications for fisheries, recreation, tourism, housing prices,” he said. However, these problems go unsolved because “agricultural and energy interests are so much more powerful.”

Even in Mississippi River basin states, lawmakers have opposed mandating maximum pollution loads. At the same time, nitrogen pollution has increased despite subsidies and the expansion of Midwestern agriculture has buried any water quality gains from increasing fertilizer efficiency. Since the 2001 agreement, biofuel production has expanded fortyfold and agriculture now contributes 73.2% of the nitrogen runoff into the Gulf of Mexico.

***

The Biden administration’s signature climate legislation, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), is expected to exacerbate the growth of the Gulf dead zone despite the benefits it may bring to the farming and biofuel industries. The legislation’s energy provisions include $500 million in grants to develop biofuel infrastructure and a renewable diesel tax credit to incentivise the use of biofuel. These measures would cover the costs of installation or upgrades to fuel dispensers, storage tanks, and distribution systems, allowing biofuel corporations to maximize production.

Geoff Cooper, President and CEO of the Renewable Fuels Association (RFA), praised the IRA as a transformative policy victory for biofuel companies. “The Inflation Reduction Act is going to present really enormous opportunities for our industry and will really stimulate a new wave of investment and innovation in the ethanol industry,” he said.

Biden’s policy will create new demand for corn and increase its value. “Farmers are now making a profit whereas, before the ethanol industry existed, they were just barely breaking even or were losing money,” said Cooper.

Cooper grew up on a farm and ranch in Central Wyoming. “I’ve been around agriculture all my life and I’ve always had a passion and interest in adding and creating value for agricultural products,” he explained.

His interest in energy security began during his time in the army. Cooper was deployed overseas in the Middle East and witnessed firsthand the dangers of foreign oil dependency. After his service, he worked for the National Corn Growers Association (NCGA) as Director of Ethanol Programs at the beginning of the biofuel boom (2003-2013). At both the RFA and NCGA, Cooper has advocated on behalf of the biofuel industry. While his initial message evolved from securing energy to decarbonization, Cooper’s objective has stayed the same for nearly 20 years.

Cooper dubbed the last decade of biofuel growth the “Ethanol Era.” He argued that there have been a number of years during this decade that the size of the Gulf dead zone shrunk while biofuel production expanded, though recent reporting shows that the area steadily increased during this time. In addition, according to Cooper, some farmers have adopted more efficient practices like conservation tillage, covering a third or more of the soil surface with crop residue to reduce fertilizer runoff.

He explained that support for the energy provisions in the IRA relied on the environmental sustainability of biofuels. “Democrats in Congress were generally convinced that the tax provisions are in the best interest of the American public, and that they are absolutely going to be impactful in reducing carbon emissions and combating climate change,” Cooper said.

***

Twenty years ago, John DeCicco also thought biofuels were the answer to renewable energy. His early research was based on the premise that biofuels would recycle carbon dioxide (CO2). While some CO2 is initially released through the burning of biofuel to power industrial production and transportation, he believed the CO2 would eventually be pulled back out of the air once corn and soybeans were grown to produce more biofuel. Scientists call these plants the “feedstocks” of biofuel. They make up the closed cycle that justified early energy policy. DeCicco later found this cycle to be too simplistic.

After the passage of the Renewable Fuel Standard, one of the first American policies to expand biofuel production, DeCicco and fellow researchers took a closer look at the impacts of biofuels. They found that biofuel production creates a carbon debt, resulting from a change in land use from rainforests, peatlands and grasslands to corn farms. When the original plants and soil are cleared, the carbon they contained is released into the atmosphere. Researchers calculated that this process could release up to 420 times more carbon than it saves from replacing fossil fuels.

DeCicco described a long-standing division in the scientific community on the sustainability of biofuels. Certain researchers promote biofuels as a clean alternative to fossil fuels, while others consider biofuels to be comparable, if not worse, in terms of environmental harm. Much of the work on biofuels is done through computer modeling, which leaves a high degree of uncertainty. Depending on the assumptions that are made, modelers can find vastly different results from one and other.

DeCicco explains that many of the researchers in government-sponsored agencies often justify the carbon benefits of biofuels, just as he did during the early stages of his career. “They’ve been funded to analyze biofuels in support of a long-standing policy decision that biofuels are worth promoting,” he said. DeCicco explained that many of the initiatives to expand biofuel production in the early 2000s were based on older understandings. Such decisions have created institutional inertia in the scientific community to reaffirm the advantages of biofuel.

According to DeCicco, agricultural lobbyists have promoted the idea that biofuels are an environmentally-friendly alternative to oil and gas. However, DeCicco believes that the comparison between biofuel and fossil fuels is like comparing a rotten apple to a rotten orange. “How do you compare oil spills due to Deepwater Horizon to dead zones due to agricultural production in the Gulf of Mexico?” he asked.

While biofuel and corn corporations use sustainability as an argument to convince policymakers to back legislation like the IRA, many environmentalists disagree. “Corn ethanol is not a solution,” said Matt Rota, the Senior Policy Director for Healthy Gulf, an environmental advocacy group. “If you really look at it from cradle to grave, it doesn’t reduce greenhouse gases when you compare it to the burning of gasoline. It’s basically an incentive for agribusiness to grow, Monsanto to sell its corn seeds and its roundup.” Monsanto, now part of Bayer, is an agrochemical company that recently pleaded guilty to 30 different environmental crimes related to the pollution of corn fields.

Rota noted that the farm lobby has not only won subsidies and greater production incentives, but received exemptions from legislation regulating pollution. “Agricultural runoff is exempted from the Clean Water Act, the primary tool that we would use to reduce the pollution in water,” Rota said. “Farm lobbying organizations are very, very active in resisting any sort of regulation.” The result is that Gulf Coast communities and wildlife are “not taken into account when our policies are being made.”

Rota grew up in Southern Illinois, surrounded by cornfields. He explained that solutions exist to protect both the interests of farmers and the Gulf, and individual farmers are not the problem. Rota listed practices such as leaving buffers between streams and farmland, using precision agriculture, or planting cover crops that can protect surrounding water bodies from nutrient pollution. “[These] are not necessarily decisions that farmers can make if they are renting the land,” he said. “A lot of these lands are owned by large agricultural firms and it’s about maximizing yield and productivity as opposed to making sure that the land is well taken care of and [protecting] fisheries.”

As nutrient runoff increases, the destruction of marine habitats along the coastline will continue to worsen. “Shrimpers are losing money and cannot afford to feed their families,” said Roishetta Ozane, the Environmental Justice organizer at the Power Coalition for Equity and Justice, a New Orleans-based advocacy group. “What happens in the Gulf affects all of us: our fish, our shrimp, our oysters. A lot of the folks here, their livelihood is based on fishing.”

Ozane is from Southwest Louisiana and began her work in environmental justice through social media. “I would just post on Facebook: Who needs help? How can I help you today? How can I pray for you?” she said. “And people would inbox me and I would help them the best I could.”

She explained that while pollution itself does not discriminate, divisions become clear in the ability to recover from pollution. “For years and years, low-income communities have experienced a legacy of health disparities because of the disproportionate burden of pollution,” she said. “Political infrastructure not only causes damage to our wildlife fisheries in our environment, but also to our health and safety hazards in Black, Brown, and Indigenous communities.”

Both Ozane and fisherman Chris Nelson agree that legislators must keep people living along the Gulf Coast in mind. While those upriver may have more political capital, the Mississippi carries the consequences of misguided environmental policy downstream, where residents of Gulf Coast states pay the price.

“[Policymakers] need to look further upstream and think about what’s causing the dead zone, where that water is going, and what it’s doing to the coast,” said Nelson. “I don’t see anyone really doing much about it… that’s one of the things that disturbs me about science in today’s world: it seems to be driven by a lot of politics.”