“If a bullet should enter my brain, let that bullet destroy every closet door in the country.”

Harvey Milk said upon his 1977 election to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. One year later, a colleague found his body in city hall, riddled with five bullets. Milk had been assassinated by Dan White, another San Francisco supervisor, and he quickly became a martyr in the burgeoning gay rights movement. Forty years after his death, Milk remains an icon, an inspirational politician whose idealism and boldness in calling for gay people to come out transcends his era.

Born in New York in 1930, Milk moved to San Francisco in 1972 before becoming the first openly gay elected official in California. His election came at a time of national upheaval. After gay activists in Miami passed a law prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, fundamentalists Christians rallied to repeal the ordinance. Riding public backlash, they lead a successful campaign with seventy percent voter turnout. Sensing opportunities for political gain, conservative politicians across the nation embraced anti-gay platforms.

In San Francisco, the political landscape differed considerably. In 1977, the New York Times estimated that between 100,000 and 200,000 of San Francisco’s 750,000 residents were gay. Although pockets of conservatism remained, George Moscone won the 1978 election for mayor on a liberal platform that emphasized his role in passing a law that legalized sodomy during his tenure in the state assembly.

It was in this context that Milk rose to prominence. As the owner and manager of a camera shop, Milk founded the Castro Village Association to promote gay businesses and started the Castro Street Fair to attract new consumers to the neighborhood.

Nevertheless, openly homosexual candidates for public office were hardly taken seriously.

“When Milk began campaigning, the media giggled and treated him as the UFO candidate,” Meredith May wrote in the San Francisco Chronicle in an article commemorating the 25 year anniversary of Milk’s murder.

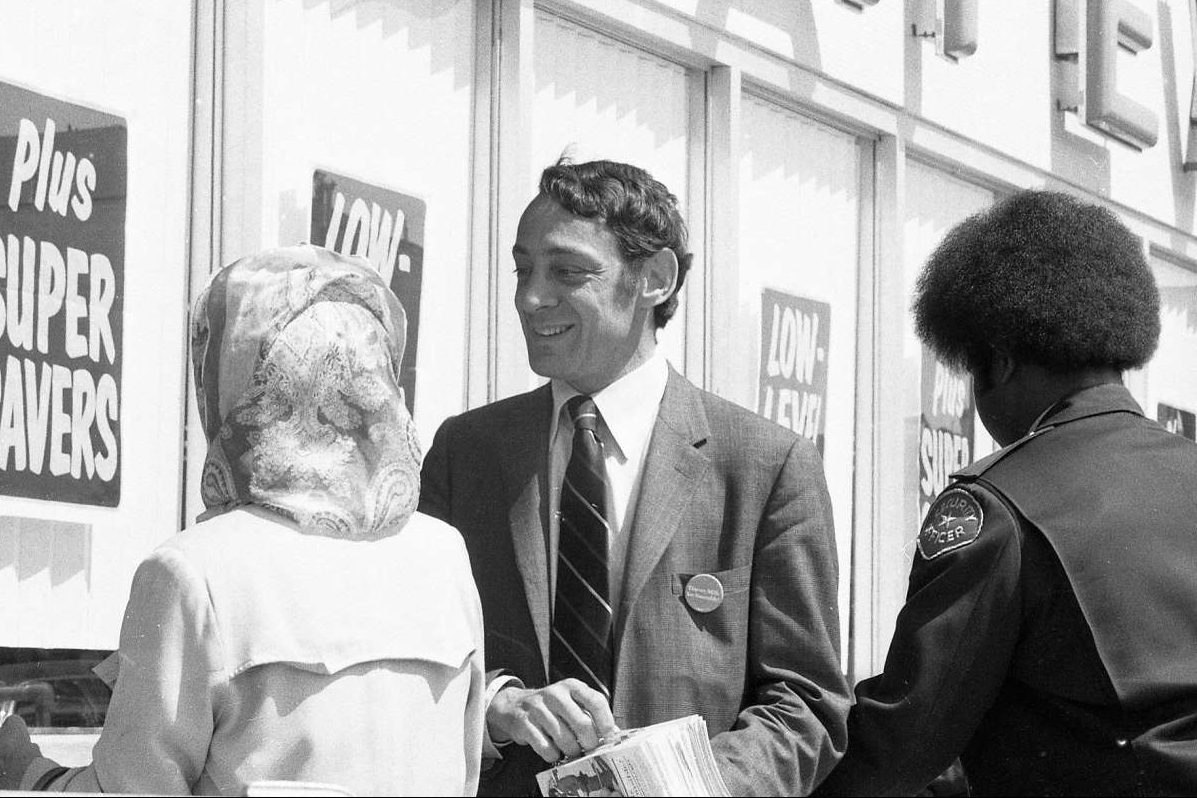

With a penchant for the dramatic, Milk’s campaigns were energetic and disorganized. He kept lists of volunteers written on scratch paper, enlisted an eleven year old to help with the campaign’s expenditures, and had volunteers make a human billboard by holding up signs during morning rush hour.

After two failed campaigns for supervisor and a loss in the race for state assembly, Milk was finally elected to the Board of Supervisors in 1978, with the support of his Castro community after San Francisco changed from an at-large system to a district-based one.

Milk’s election made national news. An article in the New York Times noted that Milk, “an avowed homosexual,” introduced his lover during his swearing in ceremony at City Hall. According to the article, Milk’s election signaled the growing political strength of the city’s gay community.

As supervisor, Milk’s first bill was a civil rights bill designed to outlaw discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. Despite being one of the strictest anti-discrimination measures in the nation, the bill passed easily, with only White, the man who would later assassinate Milk, voting against it.

This was not the only time White clashed with Milk. When Milk supported a bill for an adolescent psychiatric treatment center just outside his district, he earned White’s ire because White had made his opposition to such a center a focal point of his campaign. Known for holding grudges, White thereafter opposed nearly all of Milk’s positions.

In many ways, White was Milk’s foil. Often referred to as an “all-American Boy,” White was a star athlete in high school, a paratrooper in the Vietnam War, a former policeman and firefighter. With strong support from a police union that had grown disgruntled over the increasing tolerance for gay people within both the city and its ranks, White was elected on a conservative platform, by a district comprised mainly of Catholic working-class families.

White became a supporter of Proposition 6, a statewide measure banning gay and lesbian teachers. Largely because of Milk’s advocacy and ability to recruit powerful allies, the measure was defeated by over one million votes.

“I was taught by heterosexual teachers in a fiercely heterosexual society,” Milk said in his campaign against the initiative. “And no offense meant, but if teachers are going to affect you as role models, there’d be a lot of nuns running around the streets today.”

In an op-ed published in the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner, former governor (and future president) Ronald Reagan voiced his opposition to the measure, writing “Whatever else it is, homosexuality is not a contagious disease like the measles.”

Several days after the election, White resigned his position on the board of supervisors, only to ask for reinstatement several days later. Before Mayor Moscone could publicly refuse to reinstate him, White snuck through a basement window of City Hall, shooting and killing Moscone and then Milk.

Dianne Feinstein, then president of the Board of Supervisors and now a US Senator, found the bodies.

“I tried to get a pulse in his wrist and put my finger in a bullet hole,” Feinstein told National Public Radio in a recent interview. “It was clear he was dead. And that changed the world.”

Co-founder of the San Francisco AIDS Project Cleve Jones, who was then an intern in Milk’s office, remembers marching in a vigil at the San Francisco Civic Center later that night.

“I remember standing in that huge crowd and realizing that of course it wasn’t over,” he said, referring to the struggle for gay rights. “It was, in fact, just beginning.”

In his day, Milk was regarded as an aggressive champion of gay rights, encouraging gay people to come out and rallying public support for the movement. In death, this legacy persisted.

Especially after White was found guilty of voluntary manslaughter—as opposed to murder—and sentenced to just seven years in prison, the gay community was outraged over his untimely death.

“The message for many in the Castro was that you could kill a gay person and get away with it,” wrote May.

To someone in our generation, the death threats and violence that Milk faced—not to mention the legal barriers and sanctioned discrimination—are hard to imagine.

Until 1973, the American Psychiatric Association considered homosexuality a mental illness, according to the Human Rights Coalition. It was not until Lawrence v Texas in 2003 that the United States Supreme Court legalized sodomy. Even after this, California—supposedly the nation’s liberal bastion—banned gay marriage by constitutional amendment when it passed Proposition 8 in 2008. In his first presidential campaign, Barack Obama—the Democratic candidate of “Hope and Change”—publicly opposed gay marriage, withholding full support until May of 2012.

Nonetheless, President Obama awarded Milk the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2009 with the following dedication.

“Harvey Bernard Milk dedicated his life to shattering boundaries and challenging assumptions. As one of the first openly gay elected officials in this country, he changed the landscape of opportunity for the nation’s gay community. Throughout his life, he fought discrimination with visionary courage and conviction…Harvey Milk’s voice will forever echo in the hearts of all those who carry forward his timeless message.”

Two popular films commemoration of Milk has evolved. What in 1984 was a documentary depicting the rise of a likeably ordinary man became a 2008 live-action film, starring Sean Penn, that captures a “warrior whose passion was equaled by his generosity and good humor,” according to the New York Times.

In 2016, the Navy announced it would name a ship after Milk, who served from 1951 to 1955.

“When Harvey Milk served in the military, he couldn’t tell anyone who he truly was,” wrote Supervisor Scott Wiener. “Now our country is telling the men and women who serve, and the entire world, that we honor and support people for who they are.”