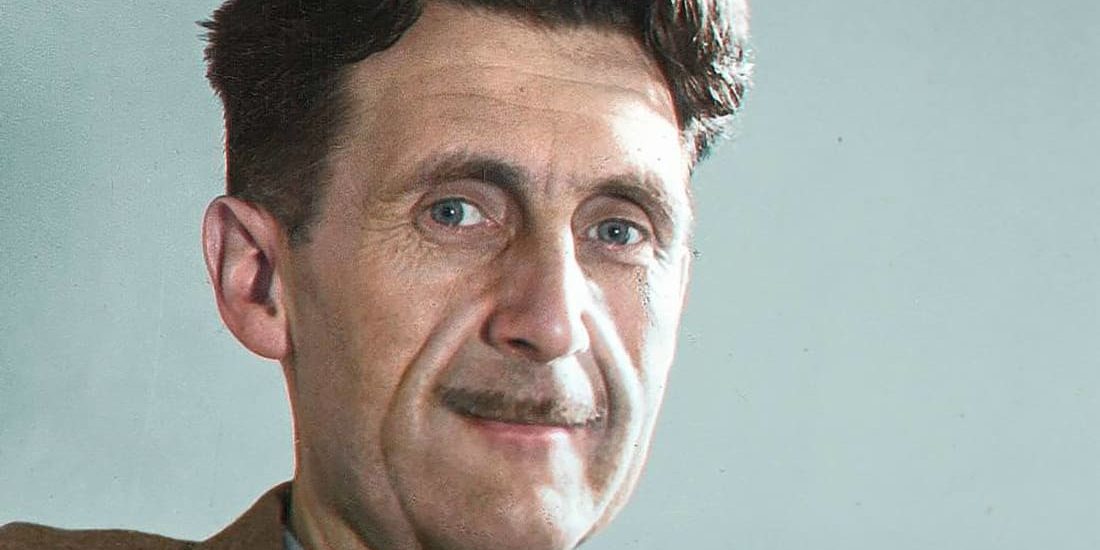

In 1946, George Orwell wrote one of the most widely read essays of the past century: “Politics and the English Language.” In the essay, Orwell lamented the state of modern English, warned against its further decay into “slovenliness,” and offered six suggestions to expunge the language’s “bad habits.” In Orwell’s account, whether by cynical self-interest or incompetence, agents in the mainstream culture begin to distort the meanings of words and phrases, rendering them meaningless and unusable. If he assigned blame to any party, Orwell directed his frustration at politicians who wished to maintain a distasteful status quo, declaring that political writing has become “largely the defense of the indefensible.”

Orwell’s essay has become at once a document of both historical non-fiction and prophecy: we are watching the processes which Orwell described play out in the 21st century crisis of democracy. In the context of our contemporary situation, we might learn some remedies for our ailing democracy by returning to Orwell, tracing the contours of how his prophecy has been fulfilled, and considering how we can reverse those trends. But first, I’d like to map out the very immediate consequences of linguistic slovenliness. My argument is as follows:

1. A republic is fundamentally a national conversation.

2. All conversations require a shared set of linguistic priors.

3. Because our mode of governance––conversation––takes place via the medium of speech, it is especially susceptible to rhetoric and euphemism, which can undermine those priors.

4. Without a shared set of priors, conversation becomes unintelligible. Our national conversation becomes a national shouting match.

5. If our conversation devolves into a shouting match, the people lose the source of their ability to govern.

6. In the absence of a functioning republic, our society reverts to its skeletal framework: a modern feudal state.

7. Finally, if power reverts to those who currently sit atop the feudal pyramid, they will seek to maintain the status quo.

1. A republic is fundamentally a national conversation.

The Latin root from which we draw the English word republic, res publica, literally means “the public thing.” The mode of republican governance is argument, debate, compromise, and collective self-rule. Senator Bobby Kennedy once said that, among other things, it was the “intelligence of our public debate” that made us proud to be Americans.

2. All conversations require a shared set of linguistic priors.

Babel laid bare the foundations upon which all human endeavor is built. So long as we build on rock––if we all agree upon a common set of definitions and grammatical norms––we can have a conversation. If we build on sand––if two speakers mean two different things when they use the same word, or if one uses a vernacular with which the other is unfamiliar––we cannot understand each other. Four of Orwell’s six rules for writing emphasize the necessity of speaking clearly: avoid vague clichés, avoid long words, avoid unnecessary words, avoid foreign words and jargon.

The need for linguistic clarity may seem academic and abstract, but in fact it can have life-changing consequences. A recent study in the journal Language revealed that court reporters are often unable to understand witnesses who use African-American Vernacular English (AAVE) in courtrooms. While court reporters must reach a 95 percent accuracy level in order to be certified in Pennsylvania, where the study took place, those same highly-qualified reporters could only accurately transcribe 60 percent of the sentences of witnesses using AAVE. Unless courts specifically appoint juries that understand AAVE, the American legal system deprives many black defendants of their constitutional right to a trial by a jury of their peers. Linguistics matter.

3. Because our mode of governance––conversation––takes place via the medium of speech, it is especially susceptible to rhetoric and euphemism, which can undermine those priors.

In the Athenian playwright Aristophanes’s comedy Clouds, a humorous debate erupts between the personified arguments Moral and Immoral. Eventually, the lesser argument (Immoral) wins by using flashy rhetoric and subverting the superior argument (Moral). Aristophanes’s play reflects a widespread concern in the ancient world: that rhetoric had debased debate into a competition of wordplay and trickery, instead of the substantive, weighty public debates found in Thucydides or Herodotus. In fact, when the first rhetoricians came to Rome to teach their craft in the second century BC, the Senate banished them from the city in fear. Our republican forebears were right to be concerned.

Euphemism blunts the hard edge of truth. Euphemism obfuscates, hiding one concept by shielding it behind a gentler, more palatable word that often means something else entirely: symbols of white supremacy, revivified decades after the Civil War, become “heritage, not hate,” billionaires become “people of means,” and torture becomes “enhanced interrogation.” Rhetoric avoids the substance of arguments and relies instead on hyperbole, vague clichés, and the rhythm of sentence structure. While debaters stand in the gap of an argument, take their opponent’s rebuttals head-on, and repel all the assaults of the other side, rhetoricians sidestep their opponent’s charge, drop contentions, and hurl accusations in mass in the hope that something will land. Orwell especially decried the pretentious, overwrought style of political oratory: “The inflated style is itself a kind of euphemism. A mass of Latin words falls upon the facts like soft snow, blurring the outlines and covering up all the details.”

4. Without a shared set of priors, conversation becomes unintelligible. Our national conversation becomes a national shouting match.

A brief survey of just the names of some popular political programs demonstrates our devolution into a shouting match. Alex Jones’s fake news platform, which once averaged 1.4 million daily viewers, is called InfoWars. Blaze Media, which, as of June 7, 2020, claims “an aggregate reach of over 165 million each month,” features the show Louder with Crowder. A 2019 Showtime drama about the former Fox News chairman and CEO Roger Ailes, based on Gabriel Sherman’s book of the same name, was entitled “The Loudest Voice.” And in 2017, Fox News quietly adopted the new motto “Most Watched, Most Trusted,” snidely implying that its rivals are untrustworthy and should not be watched. In any shouting match, the one who shouts louder will win. In the absence of critical dialogue, the loudest shouter can impose his/her ideology upon the audience.

5. If our conversation devolves into a shouting match, the people lose the source of their ability to govern.

Despite overwhelming support for gun control reform in the 21st century, the American people have not been able to enact any significant legislative change. In the aftermath of the Orlando Pulse nightclub shooting that left 49 Americans dead, support for stricter gun control reached 90 percent in a CNN poll. Following the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida that left 17 dead, 71 percent of Americans supported stricter gun control. The March for Our Lives, organized by survivors of the shooting, saw 800,000 Americans turn out in 800 rallies across the country. And yet, all the people have managed to achieve are the “thoughts and prayers” of our elected officials.

There are legitimate arguments against reform, but the fact that such an overwhelming display of support for a proposition, over a sustained period of time, has resulted in no legislation indicates a massive system failure. In a republic, the representatives ought to represent the people. If the people’s voice can be so easily dismissed, then the national conversation has ceased to be effective.

6. In the absence of a functioning republic, our society reverts to its skeletal framework: a modern feudal state.

When we adopted the system of the republic, we did not abandon the framework of the feudal state; we simply granted unto ourselves the power to regulate and govern that structure. The great American promise of equality hid the reality of our practical inequality. All men are created equal, but we do not live equitably.

Instead of the landed gentry of the Ancien Régime, we have our modern cognate: the wealthy executives of multinational corporations, beholden to no nation or democratic principles, and rarely held to account for their actions.

Instead of rule by a robust legislature, as the Founding Fathers envisioned, we have a modern sovereign. The Executive Branch, sprawling across dozens of federal departments, agencies, commissions, committees, councils, and the armed forces, groans under the weight of bureaucratic bloat. Including the armed forces, the Executive Branch employs more than 4 million Americans. According to the United States Office of Personnel Management’s most recent analysis in 2017, excluding the military, the Executive Branch still employed nearly 2,000,000 non-seasonal full-time federal employees. This is a bipartisan problem: under both parties, the Presidency has expanded to enormous proportions, waged war around the world without Congressional declaration, and passed consequential legislation by executive order.

And finally, although we lack a First Estate and the Third Estate has been neutralized, the Fourth Estate still exercises substantial sway in our governance. The outsize influence of news organizations has been on display most prominently in the Trump administration, as the President has repeatedly been caught parroting the rhetoric and ideology of Fox News. New York Magazine reported in 2018 that President Trump frequently calls Fox host Sean Hannity late at night before going to bed. And as of early 2020, at least 21 administration officials had walked through the revolving door between jobs at the Trump White House and Fox News.

But the power of news outlets extends beyond the Trump presidency. News outlets and publications have the ability to collectively direct the national conversation and point our attention at what they think needs to be discussed. When it was reported during then-Supreme Court candidate Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination process that there were sexual assault allegations against him, it took just a week for every mainstream publication to jump on the story. Within two weeks, protests had erupted across the country and the Senate Judiciary Committee had held a full hearing, listening to testimony from both Dr. Christine Blasey Ford and Kavanaugh. When Tara Reade alleged that then-Democratic nominee presumptive Joe Biden had sexually assaulted her while she was working for him as a Senate aide in 1993, the New York Times took 19 days to publish the story. The mainstream news has largely ignored Tara Reade’s story and the stories of the seven other women who have accused Biden of sexual harassment. Kavanaugh’s allegations became one of the central moments of the MeToo movement; Biden never even apologized.

For another point of comparison, when news broke that multiple women had come forward with sexual harassment complaints against then-Senator Al Franken (D-MN), mainstream outlets steered the national conversation toward the allegations right away. Under sustained media coverage, it took just three weeks for Senator Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY) to call for Franken’s resignation. By the afternoon of that same day, three dozen Senate Democrats had called for Franken to resign, and his career was over. The collection of news agencies, publications, and cable channels that compromise the national media is not a group of dispassionate spectators; the Fourth Estate directs our national conversation. In a republic, that is no small thing.

However, if we are rendered incapable of engaging in a national conversation, then we the people lose the ability to regulate the unofficial branches of our state. In the absence of self-governance, we the people are instead governed.

7. Finally, if power reverts to those who currently sit atop the feudal pyramid, they will seek to maintain the status quo.

It is always in the interest of those in power to maintain the system in which they have authority. The absence of a national conversation means the absence of reform and the perpetuation of a decaying, decrepit status quo.

In keeping with the theme of language’s plight in American politics, I will focus most of my energy on claims three and four: the collapse of our national conversation. In particular, I will focus on just one of the effects of euphemism and rhetoric, the distortion of the meanings of words. As Aristophanes demonstrates, the problems we face regarding the manipulation of euphemism and rhetoric toward the debasement of public debate are not novel; they are as old as the concept of the republic itself.

Just a century after the Senate had banned rhetoric from Rome for fear of its effects on politics, the enormously consequential orator Marcus Tullius Cicero had perfected Latin rhetoric. Over the course of his 40-year public career as a lawyer and senator, Cicero was the consummate politician, playing every side in the labyrinthine realm of Roman politics. In the Senate, Cicero was a staunch property rights conservative, defending the aristocracy against the interests of the people. In fact, Cicero was so ardent a property rights conservative that Friedrich Engels decried him as “the most contemptible scoundrel in history.” However, when Cicero stood before the people’s assembly, he portrayed himself as a champion against the excesses of the aristocratic Senate, declaring in the public forum that he would be “the people’s consul.” How could such an aristocrat declare himself a man of the people? What did it even mean to be a people’s consul, anyway? From the beginning of the republican project, political agents have distorted the meanings of words for partisan gain.

The distortion of language in the public sphere can occur either unintentionally or intentionally, and there are different remedies for the unique problems created by each. We can track these developments in two columns, A and B, below.

Track A – Unintentional Distortion

A. In political conversation, the meanings of words are often distorted

B. Often this is done unintentionally.

C. Sometimes, by ignorance or oversight, journalists or partisans will omit necessary context, resort to euphemism, or misuse different words interchangeably, such as ‘socialist’ and ‘communist’ or ‘fascist’ and ‘nationalist.’

D. At other times, in order to win a political debate, a movement and its organizers will brand themselves with an overwhelmingly reasonable label, in order to convince the public of that movement’s overwhelming reasonability.

E. If partisan opponents become convinced of their movement’s overwhelming reasonability, they may suspect the opposition of bad faith or mal-intent.

F. A republic, like a conversation, requires a shared set of priors, such as the mutual trust that all parties are acting in good faith, for the good of all involved.

G. If citizens in a republic suspect that their interlocutors are acting in bad faith, they cannot have a national conversation.

H. The system of the republic breaks down.

A. In political conversation, the meanings of words are often distorted

B. Often this is done unintentionally.

C. Sometimes, by ignorance or oversight, journalists or partisans will omit necessary context, resort to euphemism, or misuse different words interchangeably, such as ‘socialist’ and ‘communist’ or ‘fascist’ and ‘nationalist.’

Unintentional distortion of language can be misleading, present dangerous political ramifications, and discredit the source itself. For example, when the Washington Post reported on the death of an ISIS leader in late 2019, the Post’s choice of headline severely downplayed the horrifying cruelty of a terrorist leader and presented him as a docile figure. The Post’s original headline read, “Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, Islamic State’s ‘terrorist-in-chief,’ dies at 48.” The publication then inexplicably changed the headline to read, “Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, austere religious scholar at helm of Islamic State, dies at 48.” The Post’s new headline defined the former leader of the Islamic State as something fundamentally different than what he was. By distorting the language of terrorism, the Post portrayed al-Baghdadi not as the tyrannical warlord and sexual slaver he was, but a monastic figure instead.

D. At other times, in order to win a political debate, a movement and its organizers will brand themselves with an overwhelmingly reasonable label, in order to convince the public of that movement’s overwhelming reasonability.

Most of the time, partisan entities simply seek to brand their movements with such broadly appealing names that no reasonable person could oppose them. Unfortunately, a potential consequence of this sanitization phenomenon, which we are now seeing unfold, is that entrenched partisans, convinced of the exceeding reasonability of their cause, become unable to fathom the mindset of those who disagree with them. If partisan groups continue to insist upon their own reasonability, the conclusion is that their opponents are being fundamentally unreasonable. If one sees one’s opponents as unreasonable, one becomes less able to see the opposition movement as acting in good faith upon their principles.

A ‘pro-choice’ proponent might begin to question the motivations of her ‘pro-life’ counterparts. After all, how can conservatives, who decry the abuses of a coercive state apparatus, be against something so fundamentally American as freedom of choice? Likewise, a ‘pro-life’ proponent might begin to question the motivations of her ‘pro-choice’ counterparts. After all, how can progressives, who are willing to organize on behalf of animals and the climate, so callously allow hundreds of thousands of human babies to die? The conviction of one’s own exceeding reasonability easily leads to such bad-faith reasoning and suspicions of malicious intent. Unfortunately, if we see our political opponents not as good-faith citizens who happen to disagree with us, but instead as subversive agents, we lose trust in the democratic process. In a political moment wherein Americans identify more closely with their political party than even their faith or ethnicity, an absence of political charitability may endanger our capacity to engage democratically.

E. If partisan opponents become convinced of their movement’s overwhelming reasonability, they may suspect the opposition of bad faith or mal-intent.

According to the latest research, this is already the case. A 2019 Pew poll found that 79 percent of Democrats and 83 percent of Republicans had unfavorable opinions of the other party. That same poll asked partisans to compare members of their own party against those of the opposition party on five metrics: open-mindedness, intelligence, morality, work ethic, and patriotism. On every single metric, partisans were far more likely to ascribe virtues to their party and vices to those who disagreed with them.

We recently witnessed a consequence of this partisan suspicion during the controversy over coronavirus stay-at-home orders. On social media, in print journalism, and on cable networks, left-leaning commenters insisted that the disagreement over the response to coronavirus was a fight between the lives of poor people and the greed of moneyed interests. By extension, they bludgeoned skeptics of the stay-at-home orders as malevolent forces. In fact, like almost all matters in politics, the situation was not nearly so black and white. The argument over the efficacy of shutting down large parts of society was not between pro-humanity and pro-coronavirus partisans, but disagreements between reasonable people over the approach to a shared problem. Shutting down the economy has devastated the working and middle-class, 40 million of whom have lost their jobs. Many Americans are still waiting for their single stimulus check. Domestic abuse has spiked worldwide and some estimate that the lockdown may cause up to 75,000 deaths of despair in America alone. Disagreement over the coronavirus response should not have immediately triggered suspicion of sinister intent.

For democracy to succeed, all parties involved have to assume the best of each other, until evidence emerges to the contrary.

F. A republic, like a conversation, requires a shared set of priors, such as the mutual trust that all parties are acting in good faith, for the good of all involved.

Republics are fragile institutions. Forged from an implicit social contract amongst the citizenry, a republic depends constantly on the belief of all participants that the system is fair and that their partners in the mutual enterprise are acting in good faith. When citizens lose that fundamental belief in each other, republics crumble.

G. If citizens in a republic suspect that their interlocutors are acting in bad faith, they cannot have a national conversation.

H. The system of the republic breaks down.

Track B – Intentional Distortion

A. In political conversation, the meanings of words are often distorted.

B. Unfortunately, sometimes this is done intentionally.

C. Partisan entities may intentionally obfuscate or change the meanings of words in order to tarnish their opponents with an undeserved but distasteful association.

D. Conversely, partisan entities may intentionally obfuscate or change the meanings of words in order to invoke the legitimacy of some popular outside organization or theory for their own partisan gain

E. Finally, partisan entities may intentionally obfuscate or change the meanings of words in order to disrupt the possibility for meaningful conversation and instead impose an ideology upon their audience.

F. Conversations require a shared set of priors, including a commonly agreed upon set of definitions.

G. If the interlocutors disagree upon the definitions of words they use, they indicate different concepts by the same words and speak past each other.

H. If interlocutors speak past each other, conversation breaks down.

I. If our national conversation breaks down, then the system of the republic breaks down.

A. In political conversation, the meanings of words are often distorted.

B. Unfortunately, sometimes this is done intentionally.

C. Partisan entities may intentionally obfuscate or change the meanings of words in order to tarnish their opponents with an undeserved but distasteful association.

Left-identifying voters will remember the bad-faith argument, championed by Trump acolytes like Dinesh D’Souza in his 2017 book The Big Lie: Exposing the Nazi Roots of the American Left, that the Democratic party is the party of slavery. Then-candidate Donald Trump used the same playbook in 2016, calling the Democratic party the “party of slavery” on the campaign trail. This is a classic example of partisans distorting language for political expediency. The effect is to intentionally mingle several different concepts––the 1860 Southern Democratic party of the Confederacy, the 1956 Southern Democratic party of the Southern Manifesto, and the 2008 Lincolnite Democratic party of the industrial north and liberal coasts––thereby muddying the language around politics, rendering the word ‘Democrat’ useless, and confusing voters.

D. Conversely, partisan entities may intentionally obfuscate or change the meanings of words in order to invoke the legitimacy of some popular outside organization or theory for their own partisan gain

In the decades following the Moral Majority movement, traditional and social conservatives have often appealed to “Judeo-Christian values,” a cluster of words that means nothing. The Western tradition includes at least 2000 years of soteriology, eschatology, exegesis, reformation, and counter-reformation––J.S. Mill and Immanuel Kant both appealed to Christian virtues in defense of their competing moral systems. This massive and tendentious corpus of interpretation cannot in any adequate way be boiled down into the catch-all “Judeo-Christian values.” It is this degradation of language through vague terms and euphemisms that allowed the former Attorney General Jeff Sessions to pontificate upon Romans 13 in order to justify separating refugee families at the border and putting children in cages. If “Judeo-Christian values” signifies that, then the phrase is absolutely meaningless.

E. Finally, partisan entities may intentionally obfuscate or change the meanings of words in order to disrupt the possibility for meaningful conversation and instead impose an ideology upon their audience.

As Cicero demonstrated, politicians and partisan special interest groups have always distorted language to establish their reasonability or defend distasteful goals. What is terribly concerning and frightening is when journalists do the same thing. The most glaring example of such partisan distortion is Fox News’ long-running campaign to render the word ‘socialist’ useless. When self-avowed democratic socialists such as Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) began to form a new progressive wing on the Democratic left, the story was not nearly so shocking as it should have been: Fox News had already been crying wolf on President Obama for the last decade. The Fox News Network’s effort to obfuscate the meaning of ‘socialist’ is part of its larger project to be a power broker in partisan politics.

In the post-election wrap up of 2009, Bill Sammon, the vice president of news for Fox News and the managing editor of their Washington bureau, gloated about calling then-Senator Obama a socialist even though Sammon himself didn’t believe what he was saying, calling his own speculation, “a premise that privately I found rather far-fetched.” When later asked to comment by Media Matters for America, Sammon attempted to rewrite history: “I have refrained from drawing judgments like that. I don’t take it’s the place of somebody like me to be saying, this guy’s a capitalist or this guy’s a socialist.”

Glenn Beck, then a host at Fox News, pushed the false narrative of Obama’s supposed socialism. When President Obama complained that there was no evidence for these claims, Beck posted a short anthology of President Obama’s supposed socialist leanings. The list is a shockingly unprofessional and lazy effort for any major news network, let alone one which constantly touts itself as America’s “most-watched” network. Beck seems to have tripled-spaced his bullet points to make them appear more substantive than they are. Some claims link to articles, but most are unevidenced accusations such as, “President Obama seizes control in massive land grabs.” For context, it appears Mr. Beck was referring to the Great Outdoors Initiative, a project to create public parks and recreation centers.

Eric Bolling, then of Fox Business, even went so far as to question if billionaire Warren Buffett was a socialist, asking “Is he completely a socialist now?” Buffett, who was worth $50 billion at the time, had suggested that billionaires like himself should be taxed more.

The most cynical effect of Fox’s linguistic distortion is that it renders the average voter unable to converse with those who disagree with her. By fundamentally destabilizing a key foundation on which conversation emerges (i.e., the definitions of the terms being used), Fox renders us incapable of having conversations on ‘socialism.’ From the outset, those who disagree will signify two or more different concepts when they use the same word, leading to linguistic confusion and the collapse of conversation.

F. Conversations require a shared set of priors, including a commonly agreed upon set of definitions.

G. If the interlocutors disagree upon the definitions of words they use, they indicate different concepts by the same words and speak past each other.

H. If interlocutors speak past each other, conversation breaks down.

I. If our national conversation breaks down, then the system of the republic breaks down.

Orwell’s critiques remain as poignant today, nearly 75 years later, as they were when he first published “Politics and the English Language.” Linguistics and rhetoric are not just academic exercises; they have very real ramifications for our everyday politics.

Of course, there will never be a polity of pure linguistics, free from the biases and consequences of linguistic distortion. The example of Cicero reminds us that partisans always have and always will try to, in the natural process of politics, use rhetoric and euphemism to make their own causes seem as overwhelmingly reasonable as possible. The solution to these unintentional distortions of language is to read our political interlocutors as charitably as possible, mutually trusting that we are all acting with the polity’s best interests in mind. We must further be vigilant against those who would intentionally disrupt the priors upon which we build our national conversation. If we cannot engage in a meaningful national dialogue, then we the people cannot govern ourselves.

More than anything else, the project of the republic has been America’s great undertaking, stewarded from generation to generation and kept safe by those who have given “the last full measure of devotion” in its defense. The American republic is our sacred trust, our eternal flame. By engaging thoughtfully in our national conversation, we hold aloft the torch of liberty and keep its flame ablaze.