Soccer in China was not always a “beautiful game.” For many years, the Chinese gleefully mocked the state of the sport within their borders. In a typical joke, one person asks his friend, “Why are you going to hell after having been so charitable?” “Because I watched Chinese soccer on TV,” the other answers. The men’s national team has quali ed for the World Cup only once— in 2008—but it lost every game, failing to score a single goal. For a country of nearly 1.4 billion people, a FIFA ranking lower than Qatar’s and Uzbekistan’s is a national embarrassment.

But lately, the jokesters have stopped joking and the doubters have stopped doubting. Like so much else in

China these days, soccer is undergoing a dramatic renaissance, and Chinese clubs are using their new wealth to build impressive rosters.

Didier Drogba, Eidur Gudjohnsen, Robinho, and Paulinho are just a few of the high-profile foreign footballers who have been picked up by clubs in the Chinese Super League. In January, the Chinese club Jiangsu Suning signed Chelsea midfielder Ramires in a £25 million ($36 million) deal that broke the national transfer record. That record lasted a week before it was smashed by the signing of Atlético Madrid striker Jackson Martinez to Guangzhou Evergrande for €42 million ($47 million).

It is unclear if these players will galvanize public interest in their respective clubs. Their signings make it painfully apparent that the homegrown Chinese soccer hero remains elusive.

But according to Kevin Moore, director of the National Football Museum in the UK, “This amounts to a real revolution in football in China. The overseas stars will draw new fans, raise the overall playing standards, and very much help the development of the homegrown players. But the question remains as to whether it will be sustained.”

And it likely will be, thanks to China’s ultimate soccer fan: President Xi Jingping. “The development of soccer has the support of the government, coming from the very top, from the President,” explained Moore. “This is the key factor.” Xi, who loves soccer as much as President Obama loves bas- ketball, dreams of a World Cup trophy for China. Last year, he created a panel of state officials, led by Vice Premier Liu Yangdong, to oversee the development of the sport.

Even more formidable than the political drive to develop soccer is the commercial one. Major Chinese corporations have pumped big money into Chinese and European clubs. In 2015, Chinese conglomerate Dalian Wanda acquired a 20% stake in Atlético Madrid, a prominent Spanish team. China Media Capital also got in on the game, investing $400 million in Manchester City, which plays in England’s Barclays League.

Alexander Jarvis, Chairman of Blackbridge Cross Borders, a trans-global company that facilitates investment and capital raising in Europe and Asia, spoke highly of the opportunities for Chinese investment in European clubs. With regard to its sudden increase he explained, “The sports sector in China is so small compared to other Asian [sports] sectors. Even South Korea and Japan— next to China, their football sectors are quite big. ”

The sports craze has pushed prices up sharply. “I think the prices for [foreign] players are outrageous,” Jarvis said, but he quickly added, “A lot of Chinese investors talk a lot about investing in football, but not many of them have actually done transactions in the space…I think there will be a bubble, but we’re at the very, very start of it.”

Investments and fandom are indeed correlated. Jarvis noted that China’s presence on the governing boards of European clubs is creating a snowball effect back home: “The more focus on football, the more media attention it gets, and the more money that’s going to be invested.” And more players like Jackson Martinez tearing up Chinese Super League pitches will mean “a larger fan base, a lot of people wanting to buy merchandise. There’d be more people wanting to engage with the football club, to learn about, to potentially sponsor it.”

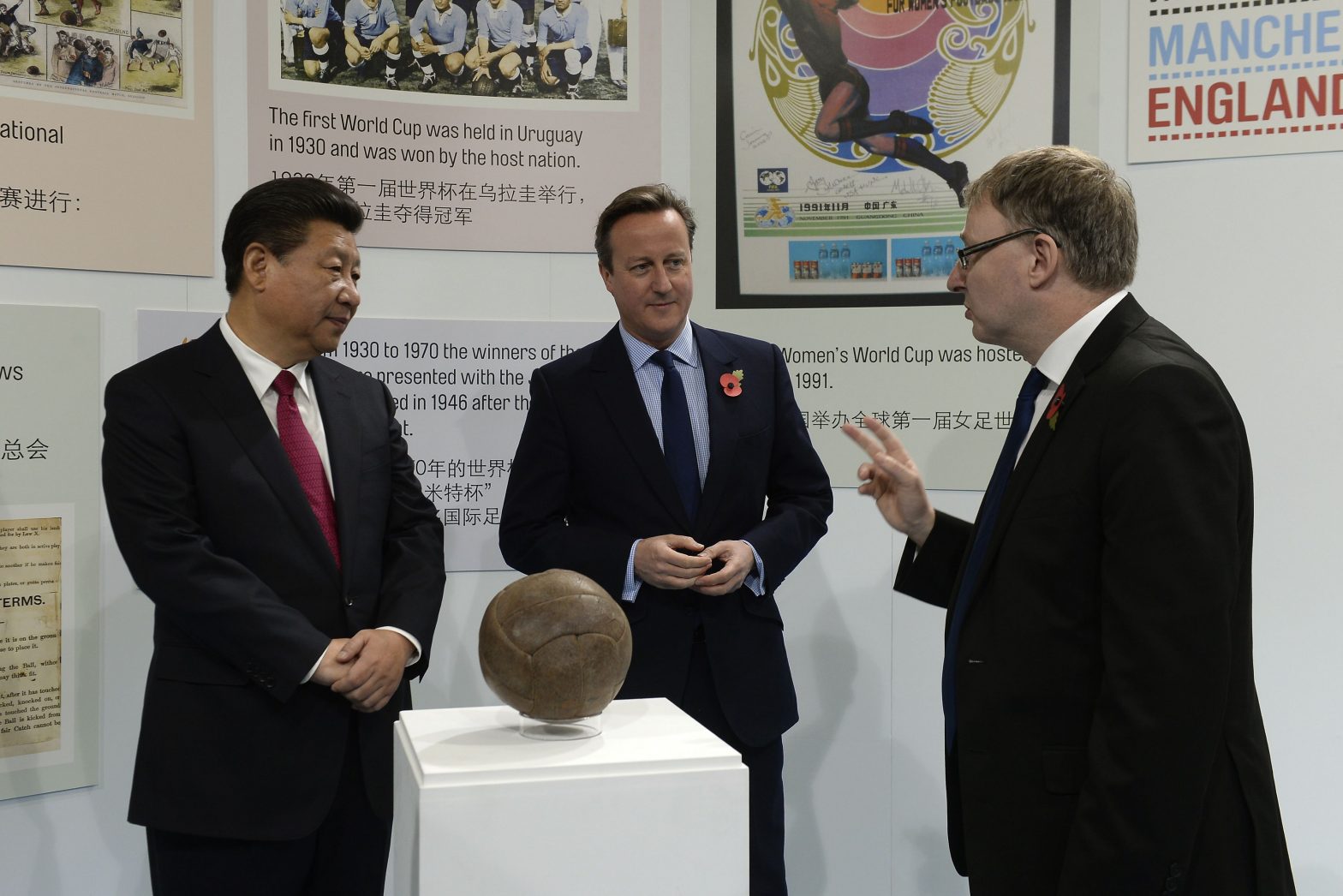

President Xi’s immense vision has many fronts: national pride and financial prosperity are two, but alone they are not enough to make soccer a beautiful game in China. What makes the game beautiful is its ability to connect people, to unite East and West, poor and rich, past and present on the same pitch. That universality has proved invaluable to diplomacy: last October, President Xi visited the National Football Museum during his state visit to the UK. Moore recounted the cultural exchange: “I gave to the President as a gift from the National Football Museum a copy of the hand- written laws from 1863, and he gave me a gift of a replica Cuju ball.”

Cuju, the earliest known form of soccer, was played in China over 2,000 years ago. Although Cuju did not lead to modern soccer—the game as we know it today was codified in England in the mid-19th century—it had a similar setup, with two teams trying to kick a ball into the opponent’s goal. That distinction gives the Chinese great pride, and it makes the famous English phrase, “Football’s Coming Home” especially applicable to China. The scale of Xi’s vision is no less apparent at the grassroots level. Enter the Evergrande International Football School, established in 2012 in Guangdong Province. With close to 3,000 students and fifty full-sized pitches, it is the largest soccer academy in the world. Its staff includes more than twenty Spanish coaches approved by the Real Madrid Foundation, whose partnership with Evergrande allows select star students to train in Europe. It is a powerhouse of homegrown soccer talent. And crucially, the school emphasizes academic education, a priority that appeals to wary, traditional-minded Chinese parents. Given the school’s reputation and high coaching standards, Guangzhou Evergrande could soon become the best club in Asia, with a roster full of domestic players.

But despite its hundred thousand new soccer fields and promising prospects, China lags far behind European countries, which have established soccer institutions at every level. A walk through a public space in China, whether in the city or the countryside, reveals that soccer has yet to catch on with the younger generation like it has in England or Brazil. Jarvis predicted, “I think it’s going to take a long time to generate real talent in China…maybe a generation.” Moore was similarly cautious in his optimism: “China could one day win the FIFA World Cup – but it will be many years from now. A realistic goal might be to get in the top twenty nations in the next decade or so.”

The Chinese women’s national team, currently ranked 17th and always in serious World Cup contention, is already there. But the men who could one day hoist the beautiful game’s most beautiful trophy still sleep in the dorms at the Evergrande Football School, dreaming Xi Jinping’s great dream.