Elbridge Gerry, the namesake of one of the most famous and hated partisan practices in politics, would likely have been remembered as just another founding father were it not for one fateful bill he signed as Governor of Massachusetts. Gerry signed a redistricting bill in 1812, under intense pressure from his party, the Democratic Republicans. The bill created districts of bizarre shapes that were clearly drawn to benefit the Democratic Republicans. In response, the opposition party, the Federalists, published a cartoon that depicted one particularly serpentine district as a salamander, with the headline “the Gerry-mander.” The name stuck, and the practice of gerrymandering has cemented itself as Elbridge Gerry’s legacy.

So what is gerrymandering? Gerrymandering is the process of drawing legislative districts according to partisan lines in an effort to win as many seats as possible for the party that drew the district lines. The two main methods to achieve this are called “packing” and “cracking.” Packing involves cramming as many supporters of the opposing party as possible into one district in order to dilute their influence in surrounding districts. Cracking is essentially the opposite: supporters of the opposing party are divided into many districts, with the aim that they will make up a small enough portion in each district to lose elections. The ultimate goal is to maintain enough of a majority in as many districts as possible to win there and to pack opposition voters together in as few districts as possible to cause an overwhelming victory.

Redistricting occurs every ten years, after the national census, to account for shifting populations. Gerrymandering has been a common political tactic since its origin in 1812, but it has seen some changes over its history. The Voting Rights Act of 1965, for example, made racial gerrymandering, drawing districts to diminish the influence of a protected minority, illegal. After this Act was passed, the 1968 ruling Thornburg v. Gingles set forth a set of criteria to determine whether a district was racially gerrymandered. One result of this ruling was the legality of majority-minority districts that consolidate minority voters in a way that often enables them to elect more diverse candidates. However, some Democrats worry that majority-minority districts have the effect of packing people of color and limiting their overall influence.

In most states, district maps are drawn by the state legislature, meaning that whichever party holds the majority in a redistricting year has the ability to gerrymander the map to their own benefit. Maps drawn by independent commissions or divided governments, however, tend to be better at protecting minority communities and tend to be more responsive to the will of the people. Still, many state governments are reluctant to relinquish control over districting. Currently, many of the most gerrymandered districts are in Republican-controlled states because the party made massive state-level wins in 2010, right before the 2011 redistricting.

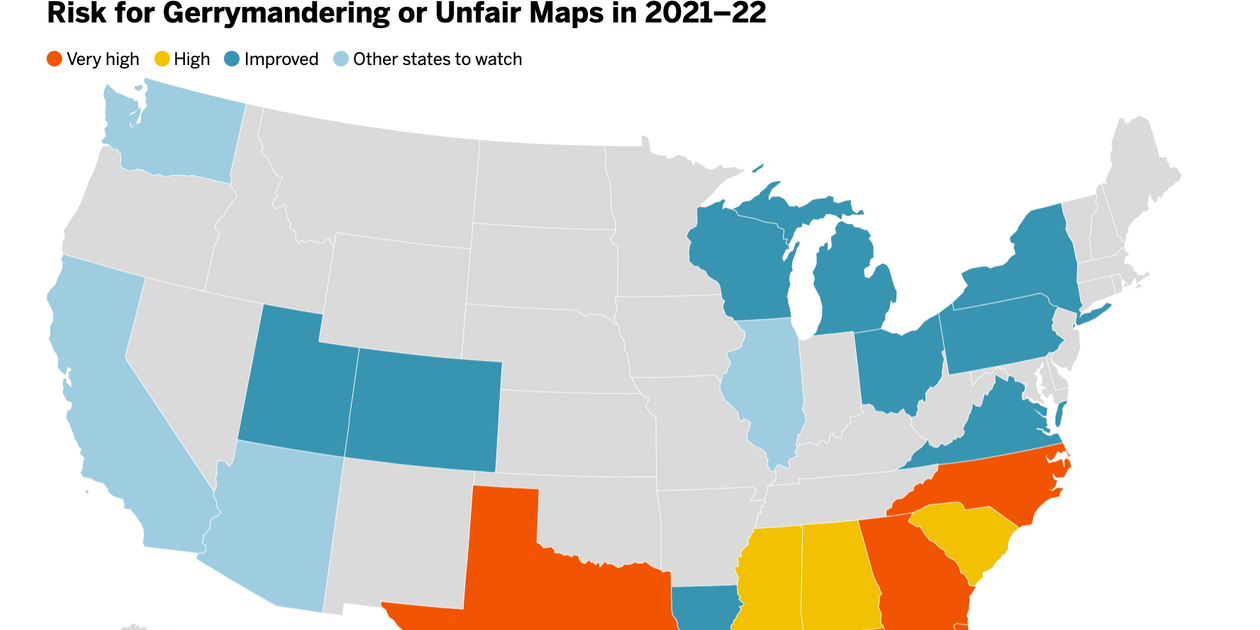

The next round of redistricting will occur at the end of this year and into 2022, and it promises to be even more challenging than usual. The Brennan Center suggests that we will see “a tale of two countries,” with many states operating with newly enacted reforms and others with even more room for unfair districting compared to 2011, when some of the most gerrymandered districts in history were drawn. Among reforms are changes in who will actually draw the maps. In many states, the task of drawing maps has been transferred to independent commissions or will be shared by a divided government. These governments will either have to agree on a map or transfer the responsibility to the courts. In either case, district maps will likely be far more fair and nonpartisan than they historically have been.

The courts have also complicated the process of redistricting. The 2013 Shelby County v. Holder decision (which has had many disastrous effects, among them increased gerrymandering), limited many protections of the Voting Rights Act. In 2019, the Supreme Court ruled that federal judges do not have jurisdiction over partisan gerrymandering, refusing to condone it, but labeling it a legislative issue. This decision does not prevent state courts from ruling on the matter though, and the Pennsylvania and North Carolina state Supreme Courts have ruled that extreme partisan gerrymandering is unconstitutional according to their state constitutions. The results of the 2020 Census will obviously affect redistricting, and the data itself from the census has been delayed due to COVID-19. Many states are unsure of when they will be able to access census data, and the later this data is accessible, the less time courts will have to challenge unfair maps.

With the Supreme Court reserving judgement on partisan gerrymandering and with state level measures unable to change how Congressional districts are drawn, the impetus now falls on Congress to act against gerrymandering. Part of the Democrats’ H.R. 1, which recently passed the House and was introduced to the Senate this week, would require states to use independent commissions to draw their districts. Ending gerrymandering should be a top priority for Democrats, and Republicans have a legitimate interest in the effort as well. An opinion piece for The Washington Post suggests that Democrats put reasonable voter ID laws and mail-in voting security on the table as enticements for Republicans, which is a compelling argument. Ultimately, Democrats and Republicans alike should aim to make the next election season as sane and reasonable as possible. An important first step, which is admittedly more appealing to Democrats, is to end partisan gerrymandering.