Jimmy Hatch reads the prologue of Harold Bloom’s How To Read and Why every morning. Years before coming to Yale, while serving as a Navy SEAL, he brought Bloom’s book Genius to the mountains of Afghanistan.

“I was reading it as a kind of translation for someone who didn’t have a lot in the way of formal education, to get a grip or at least an idea of who was great, why they were great, what they did to become great, at least in the mind of this professor. The book was like another world for me. It took me out of the ugliness for a little bit.”

Jimmy, an Eli Whitney student in his first year at Yale, speaks to me in the Whitney Humanities Center, minutes before we file into a Directed Studies lecture. His voice, full and rising from the stomach, slips into a reverential quietness.

“I emailed [Bloom],” Jimmy recalled. “I just said, ‘Hey, thank you for writing this book. I’m in this really bad place in Afghanistan, [and this book has] been super helpful to me.’ And he wrote back a few days later, one word: ‘Survive.’”

Jimmy’s story follows a fittingly poetic throughline: When he arrived at Yale, Professor Norma Thompson, Director of Undergraduate Studies for the Humanities major, introduced Jimmy to the influential literary critic.

They bonded immediately. “It’s the first time the two of them have met and [Bloom] says to me, ‘Now, Norma, I don’t want any pushback, but Jimmy’s going to take my class,’” Thompson described.

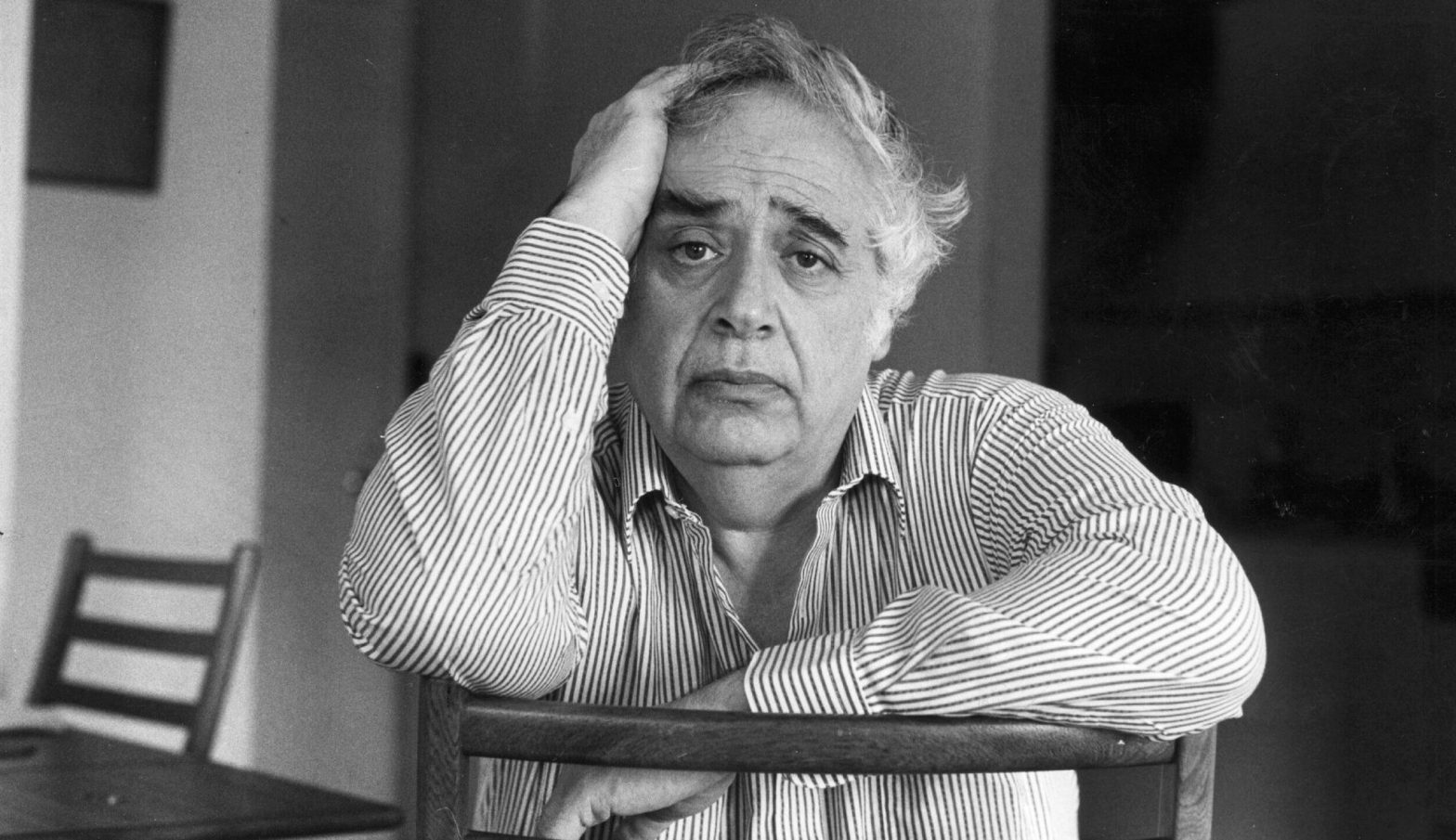

Bloom taught a Shakespeare course to Jimmy and his classmates—in his 65th year as a professor at Yale—until he passed away on October 14, 2019. It’s rare for a literary critic to become a household name, but the flurry of obituaries and social media posts trailing his death suggest that Bloom’s colossal oeuvre and outsized personality have been stamped into public consciousness. The great canon-shaper is near canonization himself.

However, Bloom’s place in public memory is riddled with controversy. Critics of the Western canon accuse him of shortchanging women and writers of color while championing the white patriarchal elite. His legacy is dogged by allegations of sexual misconduct. The same fervor with which admirers exalt Bloom is echoed by those who criticize him.

***

Bloom, born in 1930 to Orthodox Jewish garment workers in the Bronx, was a gluttonous reader. He described in a 1991 Paris Review interview skipping children’s literature to read the American modernist poet Hart Crane in his early youth. Demurring when asked if he really could read 1,000 pages per hour, he scaled the number down to 400. He declared notoriously that “Shakespeare is God,” such was his conviction that Shakespeare singularly reinvented the human condition.

After graduating from Cornell in 1951, he received a Ph.D. from Yale in 1955. He quickly collided with New Criticism, a mid-20th century American movement that approached each poem as a self-starting vehicle of close reading. Bloom, a passionate, flamboyant contrarian, resisted such formalist coolness. His early, ardent defense of Romanticism—returning Stevens, Shelley, and Blake to the aegis of academic scholarship—catapulted his meteoric rise at Yale. By the time he was 33, he was a tenured professor of English. In the 1970s, Bloom fell out with the department’s Deconstructionists, who believed language and interpretation were unstable. Then-President Angelo Bartlett Giamatti tailored a new position in the Humanities department for Bloom as Sterling Professor, the highest academic rank at Yale.

Around this time, Bloom also developed one of his most important contributions to literary theory: in The Anxiety of Influence, he outlines how strong poets create original work despite writing in the shadow of their predecessors.

“What he did was to make literary history as compelling as, if not more compelling than, actual history. It wasn’t a return to the old-fashioned biography of the poets. It was a new concern for what any figure read and how any poet reacted to what he did,” Yale English Professor Leslie Brisman, who has taken over teaching Bloom’s Shakespeare course, explained.

Although Sterling Professor of English David Bromwich insisted that his department would have welcomed Bloom back at any point, Bloom held onto his tenured title in the Humanities department for the rest of his career. From his lofty roost, he cut a rather lonely figure, balking against the plate shift towards socially and politically loaded literary interpretation, which he dismissively dubbed as the “School of Resentment.”

Students piled into his classes. His immense physical presence underscored the voracity of an ever-consuming mind. A 1992 Yale Daily News article profiling Bloom described students making a bingo game out of his idiosyncrasies; no doubt his personality cult played a sizable role in making him such a campus fixture. For some, Bloom’s superlative reputation made his classes frustrating. The article’s author observed wryly that Bloom’s seminar was dominated by one stream of thought—his.

***

In the shadow of his magnetic personality and campus fame, however, rumors flew about his relationships with female students. GQ published a 1990 piece entitled “Bloom in Love” brimming with innuendo about Bloom’s affairs. Four years later, Bloom’s colleague and friend R.W. Lewis shared: “I hate to say it, but he rather bragged about [his wandering], so that wasn’t very secret for a number of years.”

The most explicit charge against Bloom came in 2004, when Naomi Wolf ’83 published an exposé in New York Magazine accusing Bloom of sexual misconduct. She describes that Bloom, then her professor in an independent study course, invited himself over for dinner at her house, where he placed his hand on her thigh. In an interview with The Politic, Wolf described the 1983 encounter as “very, very traumatic.”

After the article’s publication, however, Bloom’s reputation remained mostly intact, while a maelstrom of media coverage criticized Wolf’s accusation. Headlines in 2004 spoofed on “crying wolf.” Their implied question: That’s all?

Some questioned if she embellished the story. Wolf has been frequently derided for exaggerations in her own writing. Her exposé was also published more than 20 years after the alleged assault, when the two-year statute of limitations for a criminal charge had long expired. Although she attempted to file formal grievances as recently as January of 2018, she claims that her attempts were stonewalled by the University. Still, she told The Politic, “It’s my responsibility as a mom of young adults to get the truth to come to record.”

Yale English professor Meghan O’Rourke was among those who publicly criticized Wolf’s accusations. In a 2004 article for Slate, O’Rourke argued that Wolf was muddying the waters of sexual harassment discourse by presenting ill-defined evidence and making ungrounded assumptions about Yale’s institutional response.

O’Rourke’s opinions, however, have undergone a profound metamorphosis. In an interview with The Politic, she said, “When I read the piece now, I see what I felt but couldn’t articulate to myself then: that is the struggle of someone who has been socialized to feel that it’s very hard to make these allegations, and to feel that therefore we had to present ourselves as hyper-rational when we did.”

Yet when I asked Thompson about Wolf’s accusations, she said, “It doesn’t affect me in the slightest. Wolf has been accused of not being truthful in all sorts of her work, so I just bracket it…. We should be able to speak and to be heard. But I also teach the Salem witch trials, and I know what it means to just name a person and have that accusation taken as gospel truth.”

Among the bevy of Bloom’s correspondences the Beinecke Library has preserved, his letters to the poet John Hollander, whom he addressed as “Foofoo,” bring to mind the lustful Bloom of rumors. Around 1965, in the early years of his teaching, Bloom wrote to Hollander, “I am trying to give up my major vices (lady graduate students, gluttony, sado-masochism, melancholy, paranoia) but it is not easy.”

Such letters reveal the muddiness of stepping back into the past. For Bloom’s time, such relationships, if consensual, were technically unprohibited. Only after an assistant math professor was found guilty of sexual harassment in 1996 did Yale begin to officially ban sexual relationships between professors and students. While ironically un-Bloomian, perhaps we can only understand Bloom by considering the historical moment he inhabited.

***

I met Professor Brisman, once called Bloom’s disciple, in his Saybrook College office, where snowdrifts of papers and Romantic poetry lie in vertiginous stacks.

In 1967, when Brisman was a Ph.D. student at Cornell, Bloom visited campus to deliver a seminar. Brisman was electrified—so inspired, in fact, that he promptly rewrote his dissertation on John Milton, which he had already defended. “He completely changed the kind of thinker I was,” Brisman said.

There is still a cadre of Bloom loyalists at Yale. Thompson recounted, “Bloom was a man who collected people. He had so many friends. When [my husband] and I would be at his house on a Saturday or Sunday, somebody else would invariably drop in or the phone would ring and it would be such and such from somewhere else.”

The renowned Yale professor’s literary criticism comes out of a deep existential preoccupation: the bald truth of mortality—knowing we only have so much time to read—pushes forth the question of what we should read. As he writes in the introduction of How to Read and Why, “One of the uses of reading is to prepare ourselves for change, and the final change is alas universal.”

To pare down a list of classics, Bloom had no patience for mediocrity. He did not bar writers of color or women from his canon ipso facto, but he rejected reading poems solely for historical or cultural import. Doing so, he believed, marred their aesthetic beauty. He read the great writers in dialogue with each other, never as history’s first responders.

Not many writers have an invitation to Bloom’s dinner party of greats, but that’s all part of his plan. Does that sound aristocratic? Surely. But Bloom asserts a kind of selfishness and necessary loneliness to reading: we should not read for anything but the thing itself, nor for anyone but ourselves.

Yet despite his aesthetic idealism, he recognized the unpopularity of his position among many contemporaries. While he could be acerbic, impassioned, and exuberant with friends, he also slumped into a dinosaur-like melancholy, eclipsed by other strands of critical theory. He bemoaned the conflation of cultural criticism and literature. Marxist, feminist, postcolonial readings profaned the discipline he adored; they are not what literature is for. He envisioned himself as one of the last great defenders of his beloved canon.

At the same time, it’s hard to tell when to take Bloom seriously. “He formulated [his criticisms] in extravagant ways deliberately,” Bromwich recalled. Bloom was also known to impersonate his favorite Shakespeare character, the swinish knight Falstaff; one questions how much of his pedagogy was performance.

For many, his position belittled a legitimate concern about representation and meaning. However, although some of Bloom’s students disagreed with his beliefs about inclusion and literary merit, those conversations rarely surfaced in class. By making his seminar a sanctuary for semi-monastic literary devotion (and respect for the giant man in the chair), Bloom enacted his scholarly idealism in the classroom.

“A lot of us…bracket[ed] off his class from other aspects of his work. But some of his popular writing’s characterizations of what was happening in the academy in the ’90s seemed wrong and troubling to me,” O’Rourke observed. Nevertheless, O’Rourke found Bloom to be a generous and inspiring teacher. “It was an important class. It made literature feel vital and necessary…. It was like, ‘Oh, actually, reading comes as a way of figuring out how to deal with the sense of imperilment that we all feel.’”

Steven Tian ’20, who has taken two seminars with Bloom, became exuberant when talking about his late teacher. “He opened my eyes to a whole new universe,” Tian said. Despite Bloom’s academic stature, Tian describes Bloom as genuinely invested in his students’ lives, helping them become “more full and complete human beings.”

However, while Bloom’s idiosyncrasy makes it difficult to imagine that the department will ever be the same, Thompson admitted, “That doesn’t mean anything about how much influence he had in the university more broadly.”

***

A New York Times op-ed in October, after Toni Morrison’s passing in August and Bloom’s recent death, contemplated whether the canon wars have come to an end. Bloom’s colleagues seem to agree that this chapter already turned somewhere in the fuzzy past.

In 2019, Bloom’s position is increasingly difficult to defend. Two years ago, the Yale English department voted to revise the curriculum to include a comparative literature pathway in major. The former gateway courses to the English major, “Major English Poets,” were renamed “Readings in English Poetry”—it is no longer in vogue to elevate an elite cadre of “major” poets. New methods of textual engagement also arrive from a different kind of literary scholar: those with multi-departmental ties whom Janis Jin ’20, an English and Ethnicity, Race, & Migration (ER&M) major, describes as “hav[ing] a broader understanding of how we are supposed to read literature in the first place.”

An op-ed in the conservative publication Washington Examiner lamented that Yale English students no longer have to study Shakespeare. It’s superficially true: a student coyly evading the Bard could opt out of English 126 and play a game of hopscotch while fulfilling distributional period requirements. Although Bloom would agonize over these departmental transitions, the pace of change in the English department is still relatively glacial. In an interview with The Politic, English and ER&M major Irene Vázquez ’21 quipped that she’s taken as many English classes with white professors named Jill as she has with black women.

So where do the humanities at Yale go from here? The English department could buck its starched past, broadening the curricula and diversifying faculty hires. Expanding the writing concentration may be one avenue; Yale has traditionally been a house of critics, not creatives. One Yale Daily News article from 1994 lamented the departure of writers like Morrison, who became a tenured professor at Princeton. By contrast, if the English department truly were to lionize Bloom and his ilk, it could instead dig in its heels and vocally reaffirm its commitment to literature and the great books.

Jin suggested Bloom’s pedagogical approach continues to influence the preponderance of close-reading in Yale’s English department. “The difference between a lot of the core English classes and classes cross-listed or taught by an interdisciplinary scholar is the question of how much secondary scholarship you are reading,” she said. Jin herself is more interested in “horizontal reading”—reading writers in conversation with contemporaries—than Bloom’s temporal analysis of great poets in situ.

Vázquez, a poet herself, does not believe that reading the works of the Western canon is intrinsically wrong—she admits her love for William Wordsworth—but criticized Bloom’s personal history. “Yale has the means to bring on a more diverse English department and not continue to hire an employee facing allegations of sexual misconduct,” she said.

The loss of one of Yale’s most iconic faculty members is an opportune moment for the University’s self-interrogation. However, rather than asserting one direction or the other, Yale seems perfectly content floating in the uncommitted middle. Its relationship to Bloom seems ripe with contradictions: it has at once made a celebrity out of him—one suspects Bloom reached the apex of public fame for a literary critic—and shies away from fully embracing his breed of scholarship.

Even if the wider pathways to the English major provide one sign that the canon wars have ended, and even if cultural criticism and ethnic studies now occupy a more dominant position than in years past, Bloom’s obsession with great books can’t be historicized completely. For one, there are just far too many of his books and students. His canon is infused in high school curricula across the country, and his pupils have thoroughly suffused the academic world.

It’s hard to neatly sever Bloom’s intellectual work from the personal. His love of reading and teaching is startlingly vital and fundamentally humane. It’s hard to engage in conversation about his flaws when many at Yale know him not only as an intellectual, but also as a warm and devoted friend. But if we exclusively apotheosize or criticize him, if we turn away from this task of simultaneous reckoning, then we haven’t learned much from literature’s own messiness. Bloom is his most complicated character. However we construct our interpretations, we must try our best to understand him. Isn’t that the work he passes onto us, as readers?