This past Wednesday in Washington D.C., climate change activists re-issued cries of protest against the government. As they blocked an entrance to the White House with kayaks and chained their own bodies to its gates, they commanded attention in protesting the construction of Enbridge Line 3. Demonstrations against this Biden-administration-backed pipeline have escalated in the past month, as Indigenous leaders and allies call upon the Biden administration to stop approving fossil fuel projects.

The issue of the Line 3 pipeline speaks to a disappointing theme of our current administration’s energy strategy – namely, that of promising robust climate action, but later acquiescing to demands wholly incompatible with the greenhouse gas emission trajectories laid out by research groups such as the International Energy Agency (IEA).

As has historically been the case, climate proposals are subject to fierce partisan divide. Last week, President Biden sought to reach an agreement with Senate Republicans on his infrastructure bill and jeopardized support from key Republican supporters like Sens. Lindsey Graham (R-SC) and Jerry Moran (R-KS), whose votes are essential to overcome a filibuster. The impetus? An effort by congressional Democrats to guarantee a reconciliation bill that would enact controversial aspects of his climate agenda, such as bolstering the electric vehicle market and building a smart grid on renewable energy.

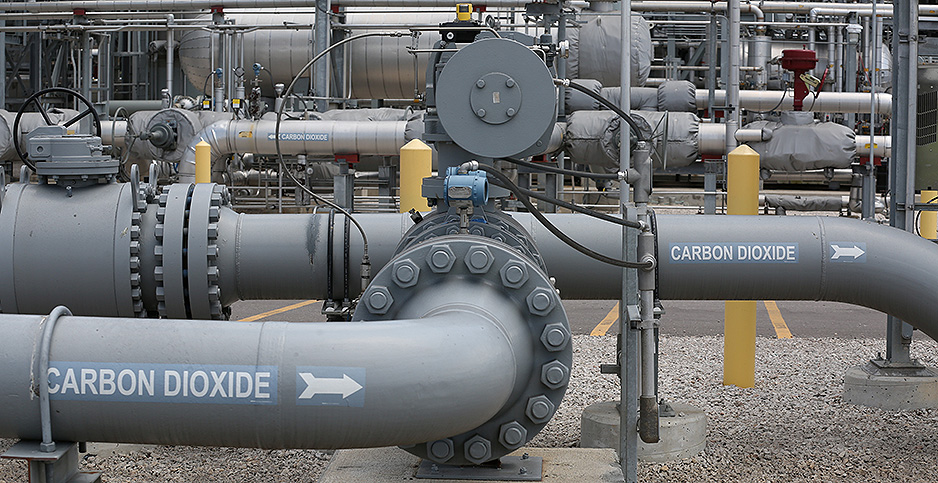

As robust climate policies continue to face deadlock in government, one technology has found widespread support amongst Democrats, Republicans, environmentalists, and fossil fuel companies alike. Carbon capture, a process by which carbon dioxide released by industry is captured, transported, and stored underground, has been promoted as a way to decarbonize several industries, such as steel and cement, without completely overhauling their operations. Capitalizing on this support, the Biden American Jobs Plan includes several carbon capture demonstration projects. The extension of tax subsidies promoting the creation of new carbon capture storage (CCS) plants has also been proposed.

While carbon capture may play some role in the future of climate policy, its contemporary uses and supporters raise questions about its legitimacy. While the Biden administration has come out in favor of CCS, other researchers and advisers are not so sure about its effectiveness. On May 13, 2021, the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council published a report recommending certain climate actions and discouraging others. Second only to investments in “fossil fuel procurement, development, [and] infrastructure repair” was carbon capture on a list of “Examples of the Types of Projects That Will Not Benefit a Community.”

There are many shortcomings with promoting carbon capture as an important par of our nation’s push against climate change. Arguably the most striking include how CCS has been mobilized by fossil fuel companies to construct an “environmentally-friendly” image while maintaining the status quo, how it falters compared to renewables’ affordability and how it exacerbates environmental health injustices.

Many liquid natural gas companies have voiced support of carbon capture and have urged the government to extend programs such as the 45Q tax credit, a misguided attempt to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. In 2018, President Donald Trump signed an expansion bill into law that raised the credit to $50 per metric ton of CO2 that is sequestered underground from $20. Trump also raised the credit for captured CO2 that is used for other purposes, such as synthetic fuels, up to $35 per metric ton from $10. These measures established carbon capture as a potentially viable part of America’s climate agenda and set the foundation for what federal support might look like.

The problem with supporting carbon capture is that these projects give companies an opportunity to capture greater amounts of CO2 rather than force them to significantly reduce their emissions. Any improvement in emissions is quickly cancelled out by subsequent projects that capitalize upon the received credit and end up releasing even more carbon dioxide.

ExxonMobil is among one of several corporations taking advantage of these subsidies. Their operations speak to the true intentions of fossil fuel companies that back CCS technology.

Since 2008, Exxon has claimed hundreds of millions of dollars in tax credits for installing carbon capture plants adjacent to their natural gas processing facilities. However, the separation of CO2 is necessary to natural gas processing with or without environmental mandates or carbon capture operations. Thus, the credit largely serves as an additional revenue stream that requires virtually no reduction of natural gas processing.

The corporation has also found a way to commodify the otherwise useless captured carbon dioxide. Exxon sells much of its sequestered gas to other oil and gas companies, which then use it for enhanced oil recovery, a process wherein CO2 is injected into porous subsurface rock at high pressures. The CO2 mixes with hydrocarbon and forces it to the surface, optimizing the oil extracted from a given deposit. The sale of sequestered gas yields an even greater profit for fossil fuel companies while indirectly generating more emissions.

The uses of carbon capture demand intense scrutiny, and the effectiveness and affordability of other technologies such as solar and wind energy further call into question its viability. A recent study looked at energy returns-on-investment, the ratio of energy output from a power plant to the energy invested in the construction, operation, and fuel, and found that the energy return from solar and wind, even in suboptimal conditions, yielded greater returns than CCS-equipped power plants. Due to its questionable environmental benefits, carbon capture presents itself as an economic strain, especially when compared to renewable energies.

Whereas the affordability of CCS is underdeveloped, solar and wind energies have benefitted from government subsidies ranging back to the 1970s. They are affordable today, not just in the United States but in many other parts of the world. The International Energy Agency argued in its World Energy Outlook 2020 that “Solar is consistently cheaper than new coal —or gas-fired power plants in most countries, and solar projects now offer some of the lowest cost electricity seen.”

Regrettably, our nation’s priorities do not form an island entire of itself. How the United States values carbon capture compared to renewable energy has important implications for the global energy transition. As renewable energy comes within reach of developing countries, a reckless detour into an unproven technology slows global investment and perpetuates issues of energy poverty, the lack of access to reliable and modern forms of energy.

The choice to invest in CCS thus neglects the most cost-efficient and globally-responsible option, in addition to granting industry another tool for holding back climate reform. A final consideration is one of environmental justice. CCS infrastructure is expensive, but the additional question of where plants and pipelines ought to be placed is one likely to negatively affect low-income communities, further speaking to carbon capture’s faults.

Taking advantage of poor towns in desperate need of tax revenue, fossil fuel and chemical companies have historically established sites in low-income communities, usually of color. Fossil fuel racism disproportionately exposes Black, Brown, Indigenous, and poor communities to health hazards generated by toxic air pollution. With the aid of government subsidies, plans have already been proposed that would increase the size and operations of existing oil and gas facilities. Because of the expenses of pipelines and transportation, CCS plants are not independently placed; they are often included as extensions of existing fossil fuel facilities. Thus, CCS investments are poised to harm BIPOC communities as they’ll be built in already- exposed communities.

These communities have expressed clear concern about carbon capture proposals. They recognize the promised carbon capture retrofits and demonstration projects within the American Jobs Plans as experiments that further exploit them. Robert Bullard, a professor at Texas Southern University, explained to InsideClimate News that communities impacted by fossil fuel companies “have a good sense of what [CCS] means: ‘I have to somehow be sacrificed for unproven technology, while others may somehow get some benefits by having more renewable, clean energy technologies.”

This fear is not misplaced. As a relatively new technology, there are many unaccounted-for considerations surrounding carbon capture plants. For instance, studies have found that CCS technology can cause nitrogen and sulfur oxide emissions to increase by 40% higher than the total emissions of a modern fossil fuel plant that doesn’t capture its CO2. There is also great potential for carbon dioxide gas leaks, and the question of pipelines and CO2 handling is often neglected in CCS proposals.

The climate crisis is already upon us, and it calls for far-reaching measures that collectively work to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. It demands creativity, not just in the ways we evaluate energy projects and the needs of citizens but also in the schoolyard fight that is politics.

Many have argued that Biden is a pragmatist and laud his attempts to foster bipartisanship. Paul Bledsoe, a consultant for the Progressive Policy Institute, frames the argument well, stating, “What they’re proposing is not what will pass ideological litmus tests, but what I think is the most ambitious approach that can get 50 votes… That’s the bottom line – really nothing else matters.”

There is an imperative to act quickly and concretely in the face of the climate crisis. However, this imperative cannot translate to settling for action that is watered-down or antagonistic to environmentalists’ goals. The deterioration of the climate and the science laying out what is needed to ensure a liveable planet should not fall within the realm of politics.

While the filibuster may grind the nation to a halt at any given moment, it has no bearing on climate change and the encroaching sixth extinction.

Carbon capture’s industrial support coupled with the support of an anti-environmentalist Republican Party alludes to its imposture as effective policy. But corporate mobilization of subsidies as well as comparisons to renewable energies and a commitment to environmental justice fully expose carbon capture as a low-priority innovation at best, and the fossil fuel industry’s latest lifeline at worst.