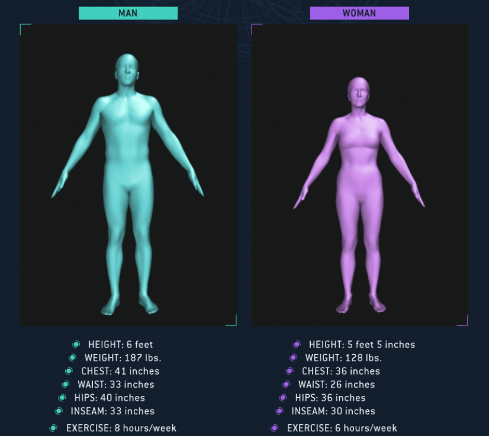

She has white skin, blue eyes, and brown hair. He has white skin, blue eyes, and brown hair. She’s 5’5” and weighs 128 pounds. He’s 6’0” and weighs 187 pounds. She has a 36-inch chest, a 26-inch waist, and 36-inch hips. He has a 41-inch chest, a 33-inch waist, and 40-inch hips. These two have perfect bodies, according to a survey of Americans done by the Treadmill Review. These bodies speak volumes about our country and our culture. They reveal who we deem desirable. They reflect who and what we value. And because of America’s obsession with physical appearance, these bodies influence our politics and economics. Our country’s beauty standards prop up systems of privilege and power, and as such we ought to consider abandoning them altogether in favor of body neutrality.

In early America, beauty standards celebrated whiteness as a way of reinforcing white supremacy and justifying slavery. According to historian Mary Cathryn Cain, “Antebellum white Americans interpreted visible whiteness as an outward projection of inner virtue….” This view of whiteness as inherently virtuous remained ingrained in American culture even after the abolition of slavery. Minstrel shows –– a post-Civil War form of entertainment in which white Americans performed caricatured versions of Black people –– portrayed Black people as dirty and criminal. Moreover, the Miss America Pageant –– a national competition initially meant to measure women’s beauty –– stipulated that all contestants be “of good health and of the white race” until 1940. And until recently, those that graced our country’s most popular magazine covers were disproportionately white.

And the harm caused by America’s narrow conception of beauty extends beyond racism.

Physical appearance has been inextricably tied to American culture’s beliefs about women’s roles in society, and because of that, beauty standards have often been imposed in an attempt to restrict women’s rights and autonomy. In the 1920s, just as women began to exercise the right to vote, disordered eating exploded alongside a new beauty standard that called for women to be as slim as possible. Throughout the 1960s and 70s, as women were advocating for political and economic rights, they faced changing beauty standards that demanded they look young and weak. In that same era, political movements also framed feminists as ugly and allowed companies to enforce restrictive dress codes.

Beauty standards have also solidified class distinctions, with America’s conceptions of physical attractiveness frequently linking closely to wealth. Throughout history, aesthetic changes, from new clothing to cosmetic surgery to hygiene products, have only been available to the upper class. Expensive imported clothing and makeup marked beauty in colonial America and were available only to the wealthy (much like today). In the mid to late 20th century, cosmetic surgeries were only available to a select few who could afford them and could find a doctor willing to do them (much like today). Even necessities, like soap, were once seen as symbols of wealth (much like today).

America’s current obsession with appearance is simply an outgrowth of this history. As such, our biases and deep desire to conform to beauty standards pervade nearly every aspect of our culture. In 2019, the U.S. fitness and beauty industries raked in 37 billion and 50 billion dollars in revenue, respectively. “Fitness culture” has grown into a mass movement for middle- and upper-class Americans, garnering a near-religious following and leading people to try ridiculous trends to stay “in shape.” And the rise of social media has only amplified this cultural emphasis on having the perfect body, with carefully curated profiles that show impossibly fit people.

At the same time, fat people, disabled people, transgender people, and people of color are perpetually and often violently reminded of their undesirability. Fat people are bullied into developing eating disorders and mental health conditions. Physically disabled people are forced to navigate a world that views their existence as an inconvenience. Transgender people are victimized in violent hate crimes. People of color are harassed, badgered, and even killed by both police officers and vigilantes. And the growing movements meant to disrupt biased beauty standards have now been commodified by corporations and co-opted by people with near-perfect bodies, effectively undermining the movement’s message.

At its core, America’s fixation on physical appearance is about status. The look of someone’s body has always been and continues to be the lens through which we judge their worth. The more fit a person is, the more deserving they are of dignity, respect, and social opportunity. Those perceived to be attractive are also often seen as smarter, healthier, and more competent than their less attractive counterparts, and thus tend to have advantages such as higher lifetime earnings and a lower likelihood of ending up in prison. Those perceived as unattractive are thus left with less political and economic power than their “attractive” counterparts. As NPR’s Leah Donnella puts it, “…beauty is a facet of power. Being considered beautiful can help you gain access to certain spaces, or increase your power in certain settings. By the same token, a perceived lack of beauty, or a refusal or inability to conform to certain beauty standards, also has really tangible consequences.”

This power imbalance might seem benign, a bit comical even. But considering our country’s history of cultivating beauty standards along race, gender, and class lines, the privilege afforded to attractive people is deeply troubling. Those who best conform to society’s beauty standards –– i.e., the able-bodied, white, and wealthy –– wield disproportionate power and can pass that power imbalance off as the result of hard work. They can bend beauty standards such that they fit a specific subset of individuals, and then claim that unattractive (read non-white, non-able-bodied, and/or poor) people have simply not worked hard enough to force their bodies to conform to a standard meant to exclude them. They can perpetuate the false idea that work and merit solely determine success in American society –– an idea that underlies our political and economic institutions.

America’s obsession with beauty must end, and body neutrality might be the way to make that happen. Instead of focusing on the way our bodies look, body neutrality calls for us to express gratitude for the ways our bodies support our everyday human efforts. At the macro level, a society that embraces body neutrality would care considerably less about how people look. There would be less social pressure to conform to beauty standards, and as such the fitness and beauty industries would likely play a much smaller role in our lives. Social media’s toxic effect on body image would diminish and, ideally, biases against unattractive people would virtually disappear. New York Times contributor Megan Nolan offered an interesting vision of this kind of society, suggesting that beauty might not be viewed as a necessity, but instead as “a nice thing some people are born with and some people aren’t, like a talent for swimming, or playing the piano.”

In general, an America uninterested in physical appearance could be more free and equal than the one we live in today. We owe it to ourselves to explore that possibility as a society.