Regarding Thomas and Leah: Their names have been changed to protect their privacy.

Last fall, in the small town of Harvard, Massachusetts, a video circulated among students. It flashed between the Twin Towers burning, masked ISIS operatives, and ninth grader Thomas’ face. The soundtrack reminded his mother, Leah–who immigrated to the United States from the Middle East–of an ISIS beheading video. Back in September, Thomas’ classmate and teammate made the montage, sending it to other students via Snapchat and text, until one recipient forwarded the video to Thomas. He showed his mother, who then reported it to the school and police.

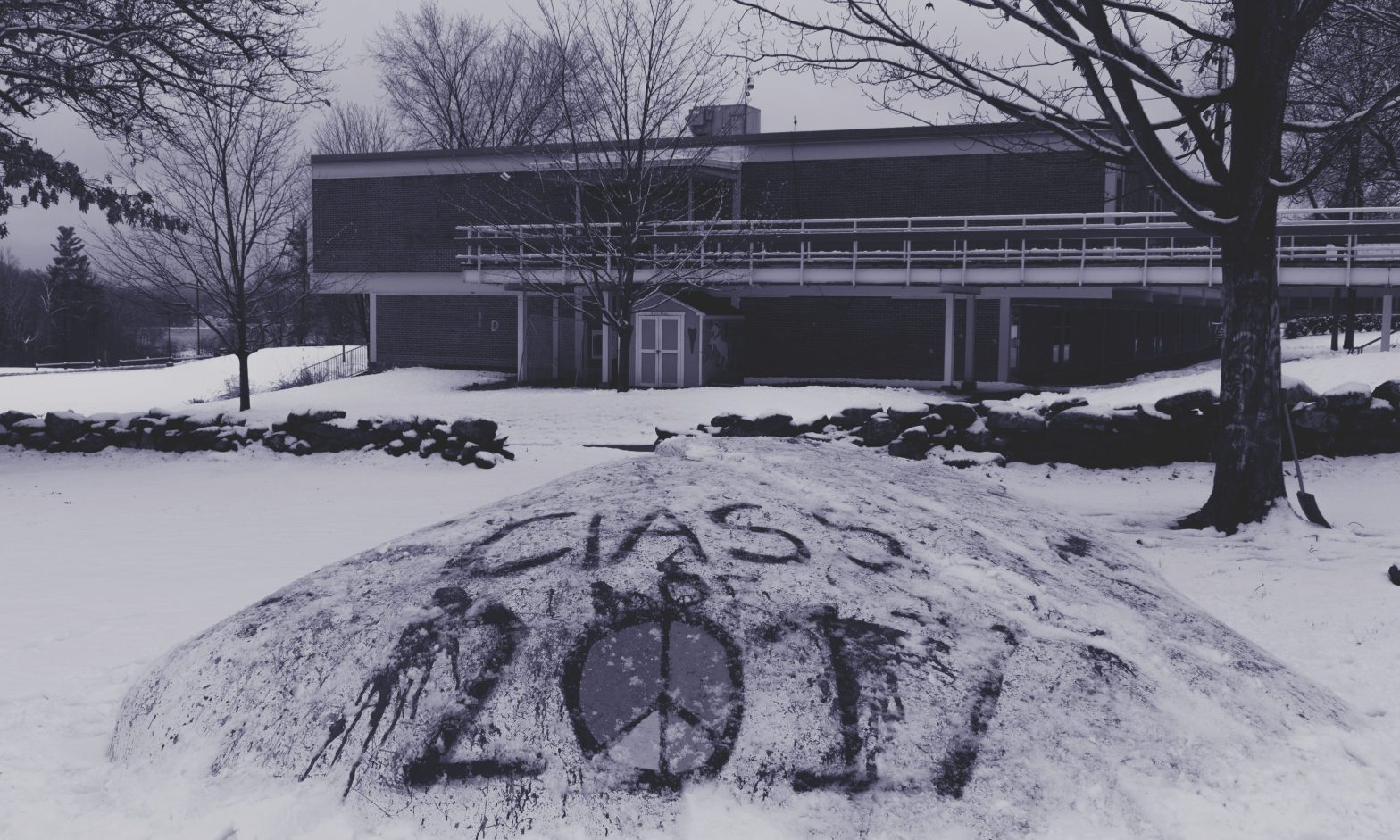

Two months later, Harvard resident Robert Curran discovered a new coat of paint on the beloved town boulder while walking his dog through the town center. The rock, centrally located and traditionally painted by the senior class, is surrounded by only a handful of buildings in downtown area—the elementary school, high school, library, three churches, town hall, and general store. That morning, the rock was covered in swastikas, genitalia, and “Trump 2016.”

The painted rock shocked the town as Harvard’s public high school, Bromfield, joined the ranks of other secondary schools across the country plagued by racist graffiti in the weeks before and after the election. High schools from Atlanta to New Haven have reported incidents of hate activity within their hallways. And much of this vandalism—like the graffiti at Bromfield—explicitly mention Trump. In November, swastikas and Trump references were found spray-painted at New Haven’s Wilbur Cross High School. In December, the New Haven Islamic Center received a threatening letter addressed to “the children of Satan,” calling Muslims “vile and filthy people,” and claiming that their “day of reckoning has arrived” because “there’s a new sheriff in town–Donald Trump.”

In a recent national survey by the Human Rights Campaign Foundation, 70 percent reported having witnessed harassment, hate speech, or bullying since the election. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), the sharp rise in hate activity is correlated with Trump’s campaign and subsequent win. The SPLC published a report that recorded hundreds of incidents–representing a marked increase in hate activity. The organization characterized this number as “a small fraction of the actual number of election-related hate incidents.”

The line between hate speech and political statements started to blur during the last election season. Faced with politically-affiliated hate speech on school property, administrators and educators must decide whether to address political context or to avoid partisanship altogether.

Superintendent Linda Dwight said she decided to separate hateful words from politics.

“We’ve tried to pull [the conversation] out of politics and talk about it as a moral issue,” she said. “That [Trump’s campaign] wasn’t the offensive part. The rest of it was. So we tried to separate those two because we don’t want to alienate the families that support Trump.”

But the rise in hate speech and harassment calls into question whether it is possible to separate slurs from politics, and whether public schools—tasked with producing civically and morally-minded citizens—should try to do so.

Richard Hersh, a Yale lecturer who serves as Senior Advisor to the Education Studies program, argued that approaching the conversation from a moral standpoint does not preclude students and teachers from discussing issues often deemed political. Hersh has significant experience with education; before coming to Yale, he taught in suburban Boston public schools, headed the Center for Moral Development at Harvard, and served as President of Hobart and William Smith Colleges and Trinity College.

“The school, whether it wants to be or not, is a moral educator,” he said. “All the big societal issues are moral: inequality of income is a question of injustice, inequality of student performance in schools because of race and class disparity, the fairness of the tax system. Issues of justice are all moral questions, but people are so unused to talking about these issues in moral terms.”

But is “moral” only a less charged way of referring to the same debates? Or would reframing the issues really change the conversation? Right-wing outlets like Daily Wire and American Thinker have criticized the Democratic Party for having a “moral superiority complex.” What happens when morality becomes as partisan as politics?

In Harvard, the moral approach has enabled community members to come together regardless of political affiliation. Instead of focusing on references to Trump scrawled on the rock, many townspeople have united to condemn bigotry through mission statements, coalitions, and committees. But Leah, Thomas’ mother, does not feel that any of these conversations are genuine or productive because of what they have left out.

The incident, called “racially divisive” in an email from the School Committee to parents of Bromfield students, has not prompted further public discussion by the school or other community groups. On Nextdoor Harvard, a neighborhood social networking site, one user posted a comment in the rock graffiti discussion thread: “There was the school incident not long ago that we school parents heard about via email, but that was never detailed, leaving us to wonder who the targets were.” Small-town gossip on Nextdoor did not bring the events into focus. After interviewing teachers, students, parents, and community leaders, it became clear that very few people knew what had happened.

Bromfield psychology teacher Kathleen Doherty surveyed her students following a schoolwide assembly about the graffiti, asking them to describe how they felt about the vandalism and the administration’s immediate response. Their reviews were mixed, generally divided into two camps: some students felt the school and community overreacted, feeding into the vandals’ hunger for attention. Others felt that outrage was warranted and expressed frustration that many of their peers did not feel the same.

The rock’s defacement has come to symbolize intolerance in Harvard. But for Leah, the school’s emphasis on what happened to the rock, rather than on what happened to her son, seems backward and disingenuous.

“The rock is the second incident,” she said. “Let’s focus on the incident with people. None of these discussions are real. It wouldn’t make me angry if they were real discussions.”

Leah’s words raise questions about how communities confront prejudice, what constitutes a genuine and productive discussion, and whether it is possible to have one without transparency. Summarizing her son’s words on the subject, she said, “It’s just a stupid rock. I’m a human being.”

When hate becomes this personal, this deliberate, and this extreme, school administrators face a dilemma. According to Leah, Principal Scott Hoffman expressed frustration that the Bromfield Handbook — a compilation of school rules and a disciplinary guide—did not contain any clauses pertaining specifically to incidents like this one; it was not comprehensive enough to offer a clear, appropriate course of action. For public schools, rulebooks like the Handbook offer some leeway for disciplinary decisions short of expulsion. But if the contents do not cover the specifics of the incident, administrators face the difficult task of justifying their decisions adequately in the absence of pre-existing protocol, especially if the perpetrator’s family applies legal pressure.

Leah has always wanted the story to go public, including names and details. But when a minor is brought to court for delinquency, all records pertaining to the case are confidential to protect the rights of children and families, including the perpetrator. To what extent the school must protect the student who made the video, even at the cost of doing a disservice to the victim, is contested. Dwight maintained that revealing any details would compromise confidentiality, which would violate the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act. Hersh affirmed that when a student’s privacy is at stake, “legally [administrators’] hands may be tied.”

Yet one might argue that premeditated hate speech targeting a specific individual is exactly the kind that must be discussed. When asked about bigotry among students, Dwight characterized prejudice and discrimination in the school as mostly subtle.

“Most of it isn’t swastikas on notebooks. It’s using the term ‘gay’ as an insult, it’s stereotyping a whole group based on misinformation, it’s shunning people that are different. We are trying to call that out and say that’s not okay.” She made no mention of anything more extreme than microaggressions and graffiti.

On Nextdoor Harvard, one user argued that political debates “should be had at the soccer fields and the transfer station,” and that “this [responding to the graffiti on the rock] is about community, a community for all of us.”

But for Leah, even supportive online forums aren’t enough. She is still looking for a “real conversation.”

Given the administration’s legal duty to protect the privacy of students, the responsibility may fall to outside groups—perhaps the various committees and coalitions that have been formed in response to the rock. Leah is confident that the community will find out eventually what happened. But in the meantime, she worries about the lack of awareness, acknowledgement, and discussion surrounding what happened to her son and how the administration handled it publicly and privately. When the incident affected Thomas academically, teachers had not been told enough to know why he was suddenly struggling.

As Thomas continues to deal with the fallout of the incident, Leah struggles with her inability to galvanize a public response and show her son that his community supports him. Meanwhile, educators and administrators work to turn hateful incidents into teaching moments, but partisan politics and privacy issues often complicate their efforts.

Despite the apparent correlation between hate activity and the election, Hersh rejected the idea that Trump was the sole cause of the increase, commenting: “Trump is really in some sense one of the manifestations of it and one of the outgrowths of a country that has become coarse. He’s not the cause of it; he’s a caricature.” But ultimately, moral education is not solely the domain of schools. In Hersh’s words: “Public figures are always a form of teacher.”