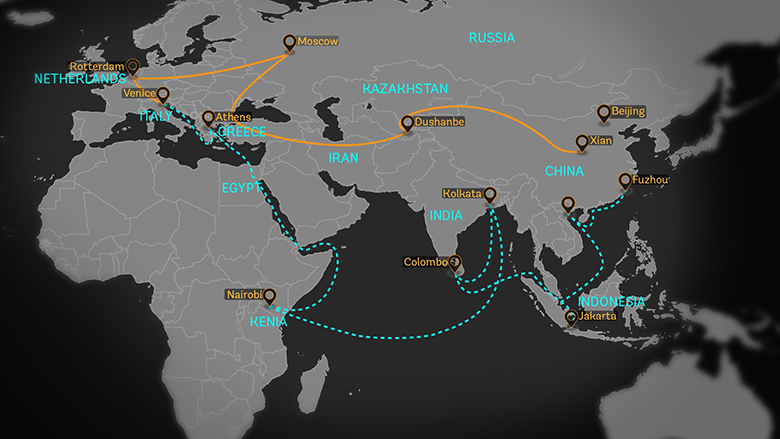

China’s Belt and Road Initiative, formerly known as “One Belt, One Road,” was announced in 2013 by President Xi Jinping. Launched with the goal of connecting countries across Eurasia, this infrastructure project is viewed as a modern-day reincarnation of the original Silk Road dating back to the second century BCE.

American politicians and scholars alike view the Belt and Road Initiative as a geopolitical battleground. As China pushes forward with its ambitious goals, securing stronger economic networks and forging stronger political relationships along the way, the U.S. watches apprehensively. Concerned by the growing transcontinental influence of China, the U.S. vehemently opposes these partnerships.

However, within this framework of bilateral competition and hegemonic footing, the responses of recipient countries, voices of the local people, and the long-term collateral damage to the environment are forgotten. Their stories are untold.

China’s multi-billion-dollar investment projects in countries, stretching as far as Belgium and Kenya, raise concerns about the ethics of fair cooperation. In theory, China promises infrastructure development and economic integration in return for greater political power and improved trade coordination.

According to Michael Cappello, professor of global health and chair of the MacMillan Center’s Council on African Studies, the Belt and Road Initiative is ultimately driven by global engagement of countries looking to advance their own foreign policies.

“Both sides are presumably thinking about their own national interests,” Cappello said in an interview with The Politic.

There is no denying that the power dynamics and difference in political leverage leave the recipient countries at a competitive disadvantage.

“[While] every bilateral relationship has the potential to be beneficial to both sides,” Capello continued, “we should not assume that all of the agreements or partnerships that China engages with countries in Africa are necessarily going to be equally beneficial to both sides.”

One consequence is debt-trap diplomacy. While infrastructure projects leave the recipient countries with highly developed and modernized transportation systems, beneath the surface, there is a crucial question left unanswered: How will developing countries finance these enormous projects?

This issue of debt sustainability has raised serious debates regarding financial transparency and predatory lending. With some countries defaulting on loans, it is unclear how they plan to repay the costs in the future. According to the Center for Strategic and International Studies, at least eight of the recipient countries—Djibouti, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, the Maldives, Mongolia, Montenegro, Pakistan, and Tajikistan—are at very high risks of debt unsustainability, facing rising debt-to-GDP ratios beyond 50 percent. And for these countries, at least 40 percent of their external debt will be owed to China.

Another issue at hand is the degree of citizenry awareness and transparency in the agreements. Critics argue that these negotiations take place without locals’ knowledge or consent, who would inevitably be most affected by these deals.

Director of the NGO “China Accountability Watch” (CAW) Jing Jing Zhang focuses on the human rights and environmental implications of investment projects in Africa and Latin America. Working with local NGOs and lawyers, Zhang strives to bring justice to the local communities unfairly impacted.

In discussing the matter during an interview with The Politic, Zhang makes a clear distinction between China as a country and the individual projects sponsored by Chinese companies. Even though the Belt and Road Initiative serves as the Chinese government’s main economic and geopolitical policy, Zhang notes, the government separates these projects in order to analyze their respective environment and human rights impacts.

In Ecuador, a Chinese company worked only with the provisional government to carry out a mining project in Cajas Nature Reserve—all of this was done without communicating with the country’s indigenous people. This failure to consult and to obtain their consent constituted a violation of Chinese law, which requires the companies to abide by both domestic law and China’s international treaties. China ratified the U.N. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which establishes the indigenous people’s rights to participate in decision-making processes and their “free, prior and informed consent” before adopting and implementing legislative or administrative measures that may affect them.

Citing this evidence, as well as other Chinese legal requirements, Zhang submitted an amicus brief in support of the Kañari-Kichwa indigenous communities’ rights to their land, successfully winning the case that halted all mining activities.

It is not uncommon, however, for Chinese companies’ managers to refuse to talk with community representatives, rather working with high-level government officials in striking investment deals. In conducting independent research on the environmental and social risks of China’s investment projects in a village in Sierra Leone, close to a Chinese-owned iron-ore mine, Zhang quickly learned from the locals that they were never given the opportunity to speak with the Chinese companies.

Chinese companies may not necessarily understand the local legal requirements or the human rights standards, Zhang admitted. But, in other cases, she highlights that they blatantly ignore them.

One effective way to ensure the local community’s rights to their own land and natural resources, according to Zhang, is by strengthening the recipient countries’ bargaining power.

“The way to change that condition is local laws in the host countries—their institution, judiciary, laws, and the governance,” Zhang said.

Aside from human rights violations, an oft-forgotten victim of the Belt and Road Initiative is the environment. While recipient countries have benefited from the investment projects, and China has gained access to valuable resources, very little has been done to curtail the environmental impacts.

Ecological damage is just one factor. According to a report by the World Wildlife Fund, as summarized by the Environmental and Energy Study Institute, there are considerable amounts of overlap between the projects and sensitive environments—threatening over 265 endangered species and many key biodiversity areas. As new infrastructure—from railways to telecommunications networks—are financed, habitats will be disrupted, animal species jeopardized, and pollution inevitable.

China is the world’s biggest investor in coal power outside its borders. According to the Global Environment Institute, by the end of 2016, Chinese companies were involved in at least 240 coal projects in 25 different countries. From 2014 to 2017, 91 percent of energy-sector loans made by China’s six major banks financed fossil fuel projects.

Although China committed to making the Belt and Road Initiative “open, green, and clean” in 2019, its continued investments in coal and other fossil fuels should raise concerns regarding rising carbon emissions. As of 2020, coal accounted for 40 percent of the overseas power plants’ capacity.

However, in a major shift in China’s attitude toward sustainable development, China told Bangladesh’s Ministry of Finance in March 2021 that “the Chinese side shall no longer consider projects with high pollution and high energy consumption, such as coal mining [and] coal-fired power stations,” according to the Financial Times.

Although it is unclear whether this surprising move is indicative of the country’s new vision for the Belt and Road Initiative, it may be a hopeful step toward change.