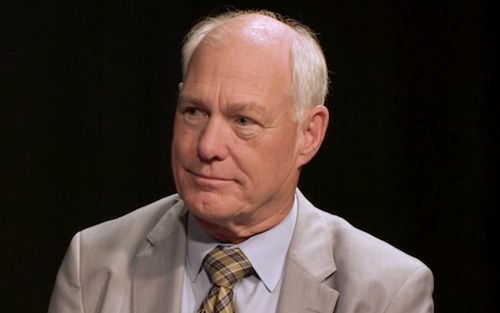

John F. Cogan is the Leonard and Shirley Ely Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution and a faculty member in the Public Policy Program at Stanford University. Mr. Cogan is a member of the Hoover Institution’s Energy Policy Task Force, Economic Policy Working Group, and Health Care Policy Working Group. He served as assistant secretary for policy in the U.S. Department of Labor under President Reagan (1981-83) and deputy director in in the U.S. Office of Management and Budget (1988-89). He also served on a number of congressional, presidential, and California state advisory commissions, including President George W. Bush’s Commission to Strengthen Social Security. He received the Manhattan Institute’s 2018 Hayek Book Prize for his latest book, The High Cost of Good Intentions: A History of US Federal Entitlement Programs (2017).

The Politic: You mention that entitlements, unbeknownst to most, began with the Revolutionary War pension program and are therefore “as old as the Republic itself.” Did general consensus exist that war pensions were legitimate and and/or necessary? Did people view them as ‘hand-outs?’

John F. Cogan: During the Revolutionary War and throughout the first two decades of the new Republic, the general consensus was that disability pensions were not only necessary, they were an obligation of the federal government. Pensions for soldiers who were injured in battle and for widows of soldiers killed in the line of duty were viewed as a necessary recruitment tool. Pensions were also viewed as a solemn government obligation to compensate soldiers and sailors for the loss of life or limb in the establishing our country’s independence. The same was true with the original Civil War pension program for members of the Union armed forces, except that the obligation was for loss of life and limb suffered in preserving the Union. But both programs were eventually expanded beyond their honorable original intentions to virtually anyone who served during the wars regardless of whether or not they suffered from wartime injuries. At that point, while the general public still strongly supported both programs’ noble original goals, public disenchantment set in.

It is much the same with current entitlement programs. There is still strong public support for the honorable intentions of major entitlement programs, namely to provide a measure of economic security in old age and a safety net against poverty, the public has become disenchanted with their excesses and high cost. So much so that the word “entitlement” has become synonymous with “hand out.”

Speaking of an idea as old as the Republic, I’ve read that both Thomas Paine (1795) and Thomas Spence (1797) even proposed variants of a ‘basic income’– was that a legitimate part of the national discourse at the time? If not, what parts of the modern welfare system do you think were beginning as ideas or even gaining heat?

The ideas of Thomas Paine and Thomas Spence did not become part of the major debates over federal policy at the time the Republic was founded, or for more than a century after that. The Founders did not believe that public income transfer programs, the cornerstone of the modern welfare state, were properly within the scope of federal powers. For the next century, Congress consistently and repeatedly rejected resolutions calling federal income transfer programs, except those that provided disaster relief.

The 19th century debates over welfare were largely confined to local and state programs. Here the debate was vigorous, but it focused mainly on providing support only for those who were unable to provide for themselves; widows with children, the disabled, and poor elderly persons. No serious consideration was given to a universal income.

The issue was seriously debated in the 1970s when presidents Richard Nixon and Jimmy Carter both proposed programs with national income floors as part of their welfare reform measures. In both cases, after initially receiving favorable reviews, the high cost and flaws of these plans were exposed in congressional hearings. Eventually, both plans were thoroughly rejected by Congress on a bi-partisan basis.

Did people (e.g., lawmakers) foresee the future unraveling of what were once strict eligibility rules? Did they know what they were getting themselves into, or were they essentially opening a Pandora’s Box by distributing these pensions?

At the dawn of the modern welfare state, it is unclear whether or not the New Deal’s architects were aware that they were opening, as you put it, a Pandora’s Box. What is clear is that through either ignorance or willful disregard, they did not heed the lessons from prior entitlements. As I noted above, earlier wartime veterans’ pensions, including pensions for World War I veterans, all began with the best of intentions and Congress eventually expanded all of these programs into costly entitlement programs; so much so that their original purposes could not be recognized. But by beginning of President Johnson’s Great Society, the thirty years of liberalizing Social Security, the expansions of the decade-old disability insurance program, and the steady expansion of eligibility for federally assisted public assistance programs, provided unmistakable evidence once a new entitlement program was written into the statute, politicians would be unable to resist calls for liberalizing its benefits and eligibility rules.

As you mention, entitlement spending increases both during a bull market (“we have more money, so let’s spend more!”) and a bear market (“we have less money, so we need entitlements!”). Is a strong executive the only person or entity that can/will actually be fiscally responsible?

If history is any guide, presidential leadership is essential to achieving significant entitlement restraint. Major entitlement programs have been cut or significantly restrained four times in the last 100 years. All four of these were led by presidents. The first, and by far the largest reduction in any major entitlement program in U.S. history, was President Roosevelt’s actions to reduce veterans pension expenditures. He proposed that Congress give him the authority to cut veterans pensions and when they did so, he issued sweeping regulations that cut benefits and eligibility by 50 percent in a single year. He then successfully fought congressional attempts to overturn his regulations. In the second instance, Jimmy Carter entered office at a time when Social Security was projected to become insolvent in five years. He proposed and led Congress’ effort to reduce promised benefits for workers who were age 60 and younger at the time. In the third instance, Ronald Reagan led an eight-year long battle with Congress to curb the growth of entitlements. By the time he left office, benefit levels had been cut or eligibility rules tightened in nearly every entitlement program; a record of restraint unmatched by any other presidential administration. The fourth instance is the landmark 1996 welfare reform measure. President Clinton led the effort by proposing to “end welfare as we know it” and signed the historic reform into law over the objections of most congressional democrats. It’s hard to think of a legislative reduction in an entitlement that was not driven by the president. So, while I wouldn’t say it’s impossible for major reductions to occur without presidential leadership, we shouldn’t count on it.

I’ve read that the period from 1983-2001–during which federal spending relative to GDP declined by 5%–is the only period of such sustained decline. What was the motivation and what was the result?

The large reduction in government spending relative to GDP during this period is unique in U.S. history. It provides an important message for the future. The decline was the result of a combination of two factors: spending restraint and strong economic growth. In the 1980s, the spending restraint occurred on domestic programs. In the 1990s, the defense spending was restrained. It is important to note, that as a result of this restraint, overall federal spending was not reduced, but merely slowed. From 1983 to 2001, inflation-adjusted federal spending rose at just under two percent per year. At the same time, pro-growth economic policies of lower tax rates, federal spending restraint, regulatory relief, and a steady monetary policy, produced nearly two decades of strong economic growth. The growth in the economy outstripped the growth in federal spending and the financial burden of federal spending declined from 22.8% to 17.6%; a 23 percent reduction. The message for the future is pay attention to policies that grow the economy. The larger the economy, the more resources we have to finance the entitlement promises made to the baby boom generation. So, growing the economy must play an important role in reducing the coming financial burden.

How much does it say about the state of our economy that people feel they need entitlements? I know automation is driving a lot of the Universal Basic Income debate…

I wouldn’t use the word “need” to characterize how people feel about the entitlement benefits they receive. Certainly, among certain, particularly poverty-stricken groups in society, a true need exists and that need should be met by helping them escape poverty. But in 2016, nearly one-third of all recipients of federal entitlement benefits were in the upper half of the income distribution prior to receiving any assistance. These individuals received over $700 billion in federal benefits that year. As for a universal government provided income, students should be mindful of its consequences. In its purest form, the program relieves individuals of responsibility to provide for themselves. As such, it can be destructive to the natural human desire for self-sufficiency and self-improvement and, thereby, enlarge the size of the permanent underclass. Also, its cost would be enormous. Conservatives that have supported the idea, including Milton Friedman and Charles Murray, have done so as a replacement for the host of existing income transfer and in-kind benefit programs. But progressives see it as an addition to existing programs. They do not propose eliminating any of the major existing entitlement programs like Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, nutrition assistance, etc.

Finally, you mention that over time, the individuals that are just outside the eligibility circle start clamoring for assistance by arguing that they are no less worthy. What do you foresee as the next expansion, if any?

With progressives and presidential candidates calling for a universal income floor, Medicare for All, expanded Social Security benefits, student loan forgiveness, and family leave assistance, there’s certainly a lot from which to choose. My guess for the next expansion is family leave, which enjoys support among certain congressional republicans and the Trump Administration. I say this not because we can afford these programs. We can’t. With a budget deficit this year approaching nearly one trillion dollars and higher annual deficits projected for future years, the federal government is not even coming close to raising the revenues required to meet its current financial commitments.