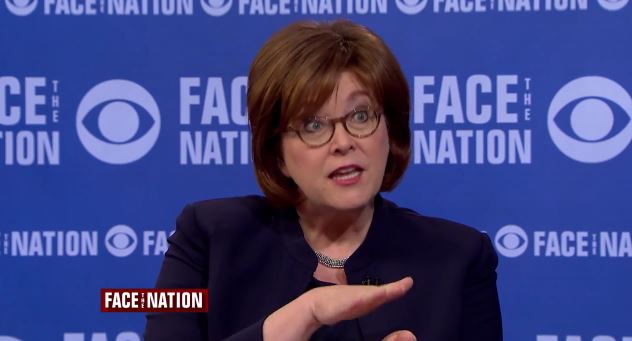

Ann Selzer can predict the future of politics. She doesn’t guess, but rather understands how to aggregate and weigh data. She founded and runs Selzer & Co., a two-person polling firm located in Des Moines, Iowa. According to Nate Silver of FiveThirtyEight, Selzer is “the best pollster in America.” She famously predicted then-junior senator Barack Obama’s big win at the Iowa caucuses in 2008, and has run most of the Des Moines Register’s political polls since 1987.

The Politic: As one of America’s best pollsters, what do you do on a day to day basis?

Ann Selzer: Where do I start? Do you mean now, or in the height of the election season?

TP: How about in the height of the election season?

AS: Well, we had projects going in and out of the field for the last month going up to the election, really the last 8 weeks. On any given day we were looking at data in progress, checking on things to make sure everything looked right, delivering to client or preparing a questionnaire, the sample, and everything to get ready to go into the field. Often all of those things in the same week. So, we were a churn factory for polls. We are a small shop so we control how many clients we take on for that sort of thing and I think last election we were probably at the maximum capacity.

TP: I was reading an article about how you “wipe the slate clean every time.” What does this mean for your practices? How do other pollsters do it?

AS: We make no assumptions about what the electorate is going to look like. When we are interviewing people, we really only want data on likely voters in the end. But we don’t know what that group of people is going to look like in the future. So, we gather demographic data on everybody, and that’s what we would call a general population. We can weight our data, because when you call people you’re going to get more older people, more women answering the phone. You need to adjust it to known population parameters. We only know that for the general population–that’s what the census shows us, what the proportions should be for each age range, what the proportions should be for male/female, what the proportions should be geographically. We can adjust for the known error we have for those [proportions] to something that is real and we know about. We don’t poll people on who they are likely to vote for if they aren’t going to vote. So we keep them on the phone for a very short period of time, then we can weight our data that we pull out our likely voters from that bigger data set and feel that now it has been adjusted.

What other people will do is factor in what actual voters have looked like demographically in the past, and there are all kinds of impressive studies about, “Well, you really need to know, ‘Have they voted before?’ because if somebody hasn’t voted before, even if they say they are going to be voting, then they are really less likely, we are going to count them a little less.” That’s what weighting is–counting some people more and others a little less. And if they aren’t really following the election, or don’t know where their polling place is, all of those things can predict for you whether somebody is going to vote.

We don’t do any of that. And the reason we don’t do any of that is the basis of a lot of social science is that the best predictor of future behavior is past behavior, and I add, until there is change. From my point of view, you’ve got people that are looking at my data saying, and this conversation actually happened, “How could you say that the African American vote is going to fall off by the amount you’re showing? Nobody thinks that is going to happen.” Well, it did happen. Nobody thinks it’s going to happen, but you don’t know. The way I look at it is we have a method, that our data will tell us what’s likely to happen, and others, if I’m being cheeky about it, they put their dirty hands on their data. That is, that their data is reflecting their view, their expectation, rather than what the voters are telling them to expect.

TP: How do you phrase your questions to avoid biasing the answer?

AS: Well, you know a lot of the questions we ask in terms of the elections are tried and true. We didn’t invent them, we all pretty much ask the same questions, the horse race question the same way. The question wording gets trickier when you are looking at issues and doing other kinds of things. It’s not the questions that bias things.

TP: Have you found that if someone is polled or called, they are more likely to go to vote?

AS: Yeah, there have probably been studies on that, I can’t cite them for you. But what you’re speaking to, is that there is a thing we call “the instrument affect”: the act of measuring something changes what you are measuring. The best example is the mechanics of measuring your tire pressure, you’re releasing air in order to see what your tire pressure is. Well, you’re releasing air from the tire, not by much, but by a little bit. The question becomes, we have interviewed them, now they told us they were a likely voter, we are not going to go any farther with them, if we determined they are not a likely voter. Turning an unlikely voter into a likely voter, don’t know. But, people getting turned off from being over-polled; we worry about that a lot. They are less likely to answer the next poll, that worries us. This last election was a year where you could kind of see that that might happen. That people got fed up with the whole thing.

TP: Is there any communication between polling agencies to make sure that doesn’t happen?

AS: Well, there is nothing that we can do to stop it from happening in terms of over-polling. We are all being paid to do it. So we are all going to go do it. There is communication between polling firms, not that we trade numbers and not that we share field dates. A lot of clients want me to go find out, “Well when are they…”. Well they are not going to tell me, and I am not going to tell them. We all want to do our own little thing. But sometimes there is something odd that you see, and people in the field that you trust and have worked with or for a long time ago, sure, there’s a fair amount of conversation.

TP: I was very invested in the election, I was reading the news every day and I would see that the NYTimes, for example, would give Hillary Clinton a 99% chance of winning. Should polls ever claim that amount of certainty?

AS: Well, I’m wondering if the pollster actually said that. Nate Silver of FiveThirtyEight, he is a poll aggregator, he is a statistician and he creates odds. His innovation was to not just throw every number into the pot and say here is the average, but to say that some polls are more equal than others and so we are going to count them more. This was a highly unusual election, the press, I think, and I gave a talk in early September about this, and Nate has been talking about it in a series of articles, about the failure to suspend disbelief, they didn’t think Trump could win so they couldn’t see the signals in the data.

In the Clinton campaign, Bill Clinton back in 1992, they were famous for having a sign in the war room that said, “It’s the economy, stupid”, to say think about that every day, that’s our message every day. And I thought you know, if there were a war room, and either candidate could have had it, it would have said, “It’s the electorate, stupid”. It was a fed up and burned out electorate that wanted change.

TP: In your experience, what else did you think was particularly unique about this election cycle?

AS: Well there was also a willingness, we saw it in our data, to take a risk. To say, you know, if we keep electing the same kind of candidate, we should expect to get the same kind of mad, again and again and again. We just did some focus groups with Trump voters around the Midwest, and one of the things that was commonly said was, “Well if the whole thing blows up, we will have to start over.” They understood that the whole thing might blow up, but they were willing to take that risk rather than to keep building and building and building this system that they were convinced couldn’t continue to work and was not working for them.

TP: In conducting polls after the election, have you found that they think Trump has been successful?

AS: Sure, his approval rate among Republicans is very high. So, he is seen as someone who, this is who I voted for, he is doing what he said he was going to do. And again, I will tell you from the focus groups, that there is a little bit of concern, a little shakiness, a little bit of worry, that he is too mouthy, but they are basically saying that he is doing what he said he was going to do, and he is moving rather quickly. They’re content.

In the same way that they would forgive the gaffes that would happen during the campaign, that continues. So long as he is doing what he said he would do, then they can be a little nervous about whether he is going to tick off the wrong person, and start something, but they are not so nervous that they think that undoes the good he is doing.

TP: Do you think that pollsters, and your company, will change their/your polling practices before the 2018 elections at all?

AS: Well, you never know. I feel like my method is defensible, just by definition, in terms of the outcome.

TP: I’ve read a lot about you and it sounds like your method is pretty tried and true.

AS: There will come a day it doesn’t work, but hopefully not tomorrow.