There is little to be certain of in the world, save the swellings of populations and seas. As the two are occurring intractably and in tandem, environmental catastrophe in coastal cities is at the fore of climate concerns. Nearly half of the world’s booming population lives within 100 kilometers of a coast, and the megacities perched by the sea are ballooning with new inhabitants, often without the infrastructure to support them. These coastal behemoths are hubs for commerce, international relations, and culture, and have had nowhere to expand but up — up until now. On April 26, the City of Busan, South Korea, in conjunction with UN-Habitat and the New York-based blue tech company OCEANIX, released the design for its forthcoming floating city. The six-hectare buoyant landmass will be anchored just offshore of Busan and will initially house 12,000 residents.

The United Nations (UN) held its first Roundtable on Sustainable Floating Cities in 2019, at which OCEANIX proposed a potential prototype layout to be sponsored by a host city. Last November, Busan signed on, and the collaborators embarked on their unprecedented project. The planned municipality, set to begin construction in 2023, will be the first of its kind in many ways: the first floating city built from scratch, the first planned carbon neutral city, and the first city built with the intention of regenerating its surrounding habitat. Its successful completion, slated for 2025, has the potential to be a trailblazing watershed event for sustainable urban development — a watercity event, if you will. Climate scientists, architects, and engineers have been discussing the possibility of floating communities as an avenue of safe coastal expansion for years, in light of rising sea levels. The melting of ice sheets and the thermal expansion of seawater have raised the global sea level by 9 inches since 1880; 2020 saw the highest sea level in the satellite record. Thus, the core intent for a municipality like Busan’s is adaptability: a site pre-equipped to remain unphased by the ocean’s accelerating swell.

Besides sea change immunity, the new community will also boast full sustainability and self-sufficiency. The offshore municipality will emit net zero carbon dioxide and waste; its design intends to glean all power from on-site clean energy generators, including solar panels and wind turbines on rooftops, and wave energy converters underwater. The residents’ food and water will likewise be cultivated on the premises in vertical farms above and below the surface of the water, utilizing the latest technologies in permaculture, aeroponics, aquaponics, and hydroponics. The farms will grow high yield, soilless crops, and city residents should expect to consume an organic plant-based diet.

The city’s anchoring method is likewise sustainably conceived. The landmass will remain moored off the coast of Busan with Biorock, a green engineering material which self-repairs and self-strengthens over time by accreting mineral molecules (mostly calcium carbonate, found in limestone) from the surrounding seawater when an electrode is electrified at a low voltage. It is used in marine repair and construction, and is especially useful in reef restoration. Coral thrives on Biorock, and the material’s electrodes release dissolved oxygen which benefits marine life. At the points where the city is connected to the seabed, project engineers plan for the Biorock to develop into small reefs, thus regenerating the aquatic habitat below the municipality.

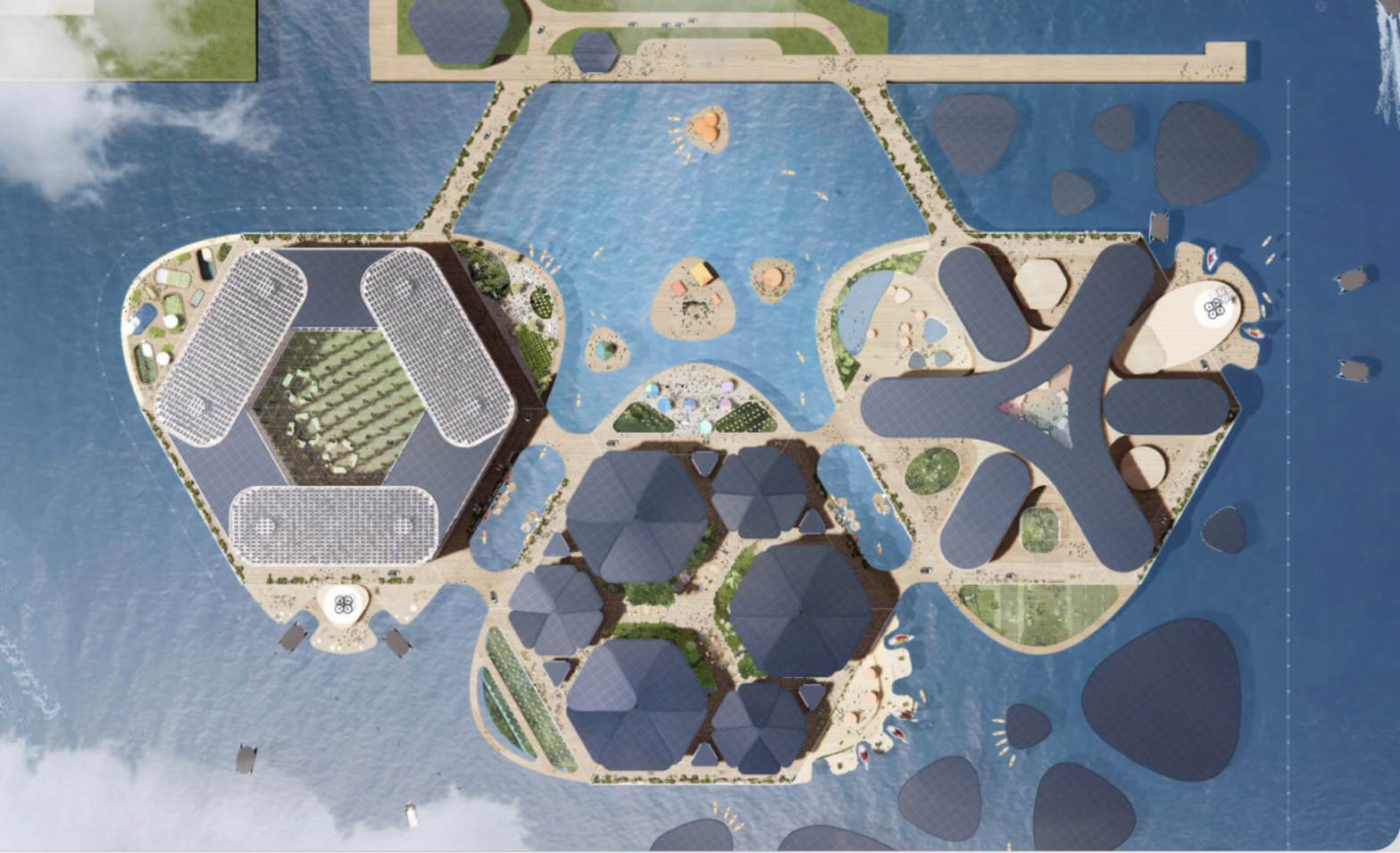

Importantly, the city’s design is also completely modular, and therefore scalable. It entails a set of distinct triangular platforms, each with a disparate function and home to unique facilities. From above, the community’s footprint looks like a game board populated with interlocking tiles — somewhat of a sleek, futuristic Settlers of Catan. The platform-based layout allows for liberal, adaptable scaling, and project leaders aspire for the offshore city to one day house 100,000. For 2025, however, the nascent community will contain just three platforms, for living, lodging, and research. The living platform will hold residences and community spaces; the lodging platform will host visitors in its greenhouses, harbor-view guest rooms, and waterfront terraces; and the research platform will facilitate maritime science and house gardens and hydroponic towers. If this pilot ecosystem succeeds, the process of expanding the community by adding various platforms will be quite streamlined: OCEANIX has designed templates for a spate of other spaces to meet a growing population’s needs, such as athletics courts, civic meeting places, and markets.

All of this, while incredibly impressive, begs the yet unanswered question: who will populate this exciting new oasis of green technology? With the project’s completion only three years away, Busan is surely considering who those first fortunate thousands will be. OCEANIX’s site provides scant detail regarding the admissions process to the highly desirable living area, only that they “build for people who want to live sustainably across the nexus of energy, water, food, and waste.” The company will likely have little or no sway in who inhabits the city, but we can imagine that the Busan government will give these values precedence as well. Given that constructing the city is estimated to cost $627 million, Busan will likely solicit wealthy patrons to occupy it. However, it is by subverting this expectation that Busan could enact a true sea change. Climate disasters including flooding and hurricanes disproportionately harm those living on the coast and in poverty: the lowest-income residents of Busan most desperately need entrance to this forthcoming climate haven, not the wealthy who can already afford elevated, flood-protected, weatherproofed housing. Equity must take precedence as we step into this new era of sustainable development. At the UN in April, Mayor Park Heong-joon said, “As mayor of the metropolitan city of Busan, I take seriously our commitment to the credo ‘The First to the Future’. We joined forces with UN-Habitat and OCEANIX to be the first to prototype and scale this audacious idea because our common future is at stake in the face of sea level rise.” Our future is common, but for some it is more imminently at stake than others. Busan should indeed take immense pride in its pioneering efforts; the world applauds its spirit of innovation. The city would be remiss, though, to not note that the existence of a “First to the Future” implies a last, and those last to the future are already drowning in the perils of today. The responsibility of the organizations and governments that are leading the charge forward is also to defend those who are truly on the frontlines of climate-based harms: the poor, the ethnic minorities, the women and children, the elderly, and those of compromised health. Let the First create space for the Last. Let the wonders of the future ameliorate, not exacerbate, the inequities of today.