There are certain historical events that only manage to squeeze in one or two lines in history textbooks. Despite their cursory mention, some of these events were pivotal, setting the stage for the major narratives of history education.

The Doolittle Raid over Tokyo on April 18, 1942 is one such unfortunately ignored topic. When it is discussed, the Doolittle Raid is simply described as Roosevelt’s revenge for the attack on Pearl Harbor. Since high school, I have studied World War II from Chinese, Japanese, Soviet, Western European, American and military history perspectives, but the Doolittle Raid hardly has a place in any of these narratives–probably because most historians do not credit the raid with enough strategic importance.

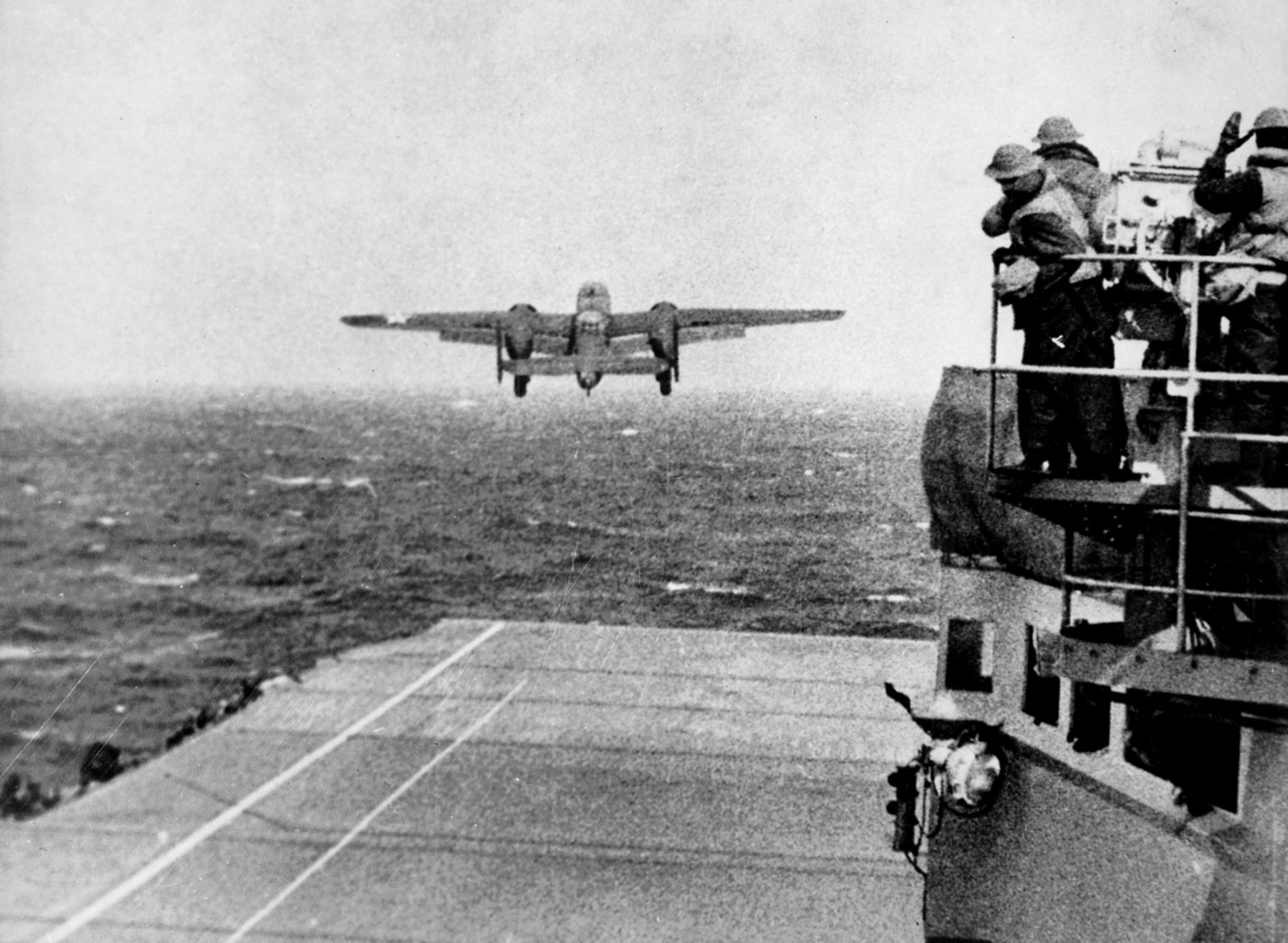

The first time I heard about the Doolittle Raid was in my Beijing high school’s most popular elective class, which focused on warfare in the 20th century. The teacher mentioned sixteen B-25s taking off from the aircraft carrier Hornet before bombing Tokyo and crash landing in China. And that was it.

Nowadays, Americans know about the attack on Pearl Harbor and the Battle of Midway, the Chinese learn about the Rape of Nanking and the Flying Tigers, and the Japanese emphasize the firebombing of Japanese cities and the two devastating atomic bombs. Different countries choose their own histories. However, as James M. Scott demonstrates in Target Tokyo: Jimmy Doolittle and the Raid That Avenged Pearl Harbor, the tale of the Doolittle Raid was a story closely connected to all these better-known events. First, the raid was widely regarded as revenge for Pearl Harbor and the decisive factor that convinced Japanese military leaders to zero in on Midway, which proved to be the turning point in the Pacific theater, tilting the balance in favor of the Americans. Second, just like the Flying Tigers, the Doolittle Raid had a close China connection: most of the crew received help from the Chinese after bailing out, but the repercussions for the Chinese included brutal retaliation from the Japanese, leaving a staggering 250,000 deaths and matching the cruelty of the Rape of Nanking. Last but not least, the Doolittle Raid was the first attack on Japanese soil in more than two thousand years, as well as the prelude to the destructive firebombing and nuclear attacks on Japan that eventually ended the war.

Aside from its intricate links to other better-known events, Scott’s masterful rendering of the Doolittle Raid makes the story an epic of ingenuity, heroism and endurance. Drawing from a wide range of primary sources, Scott leaves few details behind. From the upset of Pearl Harbor in 1941 to the last reunion of the raiders in 2013, the book proves itself as the definitive account of the Doolittle Raid.

Even though the details do not necessarily prove the relative significance of the raid, (after all, textbooks and history classes are often right about what’s more important) Scott’s effort offers us a glimpse of the intricacies of World War II: countless factors were at play for this single raid over Tokyo. From the machinations inside Washington to the survival routes along the rivers and in the mountains of China, from the inhumane Japanese treatment of prisoners to the absurd Soviet internment of one B-25 crew, from the secret training fields in Florida to the bizarrely serene sky over Tokyo, the book’s details capture a myriad of intriguing human experiences and offer a feast to anyone who appreciates fascinating stories and excellent organization of firsthand sources.

Despite Scott’s smooth, balanced storytelling, some of the content itself is unsettling. Target Tokyo documents the vicious torture of prisoners and the heinous retaliation against Chinese civilians by the Japanese. The tortures punished the captured American airmen while the retaliation against civilians aimed to prevent China from launching airstrikes against the Japanese homeland. These chapters include some of the most gruesome details I have ever read about World War II, with intensity comparable to some Holocaust literature. Nonetheless, these chapters are crucial to Scott’s historiography of the Doolittle Raid, for the aftermath, though often neglected, was an essential component to the raid.

The hellish condition of the prisons, the never-ending solitary confinement, rampant diseases, constant starvation, the trial and execution of three of the captured raiders and the survivors’ trauma were in sharp conflict with the fact that few of the Japanese torturers were convicted and punished for their war crimes. The book happily dodges the more complicated issue of the expediency of postwar arrangements in Japan and leaves the debates over humanity, war crime, witness testimony and justice to the readers.

Scott’s description of Japanese retaliation against Chinese civilians is the first of its kind in the historiography of the Doolittle Raid. The book capitalizes upon previously unpublished missionary files at DePaul University and presents the connection between Japanese atrocities and the Doolittle Raid. In the meantime, Scott notes through various sources that Washington had anticipated Japanese retaliation on Chinese soil and purposefully kept the details secret from the Chinese until after the raid. Doubtless, the Japanese were directly responsible for the loss of 250,000 lives, but was Washington partly responsible as well? One can certainly argue that Washington acted out of expediency, but since China could do little to check Japanese aggression, such retaliation could have occurred after any U.S. advance in the Pacific.

In the end, readers will be forced to ask themselves: was the Doolittle Raid worth it? The book suggests that the raid was a revenge for Pearl Harbor, but fundamental differences existed between the Japanese assault on Pearl Harbor and the Doolittle Raid on Tokyo. Although both involved the surprise factor as well as huge risks, the Japanese attack was strategic, aimed at destroying the Pacific Fleet and thwarting the United States from contending in the Pacific, while the Doolittle Raid, though fascinating and heroic, was little more than a daredevil attempt to generate positive headlines in the United States after the initial American defeats in the few months after Pearl Harbor. But would the United States have fallen apart without these headlines?

While Target Tokyo offers a definitive account of the Doolittle Raid, the book still leaves the readers with plenty of room to debate the central questions of the raid. The book surely makes up for all the neglect in history classes and textbooks; moreover, it adds important perspectives to our understanding of not just the Doolittle Raid itself but also the complexity of the Pacific Theater.